“I used to work at a nightclub in Birmingham,” says Karl O’Connor, better known as Regis, one-half of the British Murder Boys (BMB) with Anthony Child, aka Surgeon. “I remember the local DJ came in. He had that [Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit] compilation that Neil Rushton had done. He said, ‘This is the future.’ I thought, ‘Wow, this is the worst thing I’ve ever heard in my whole life!'”

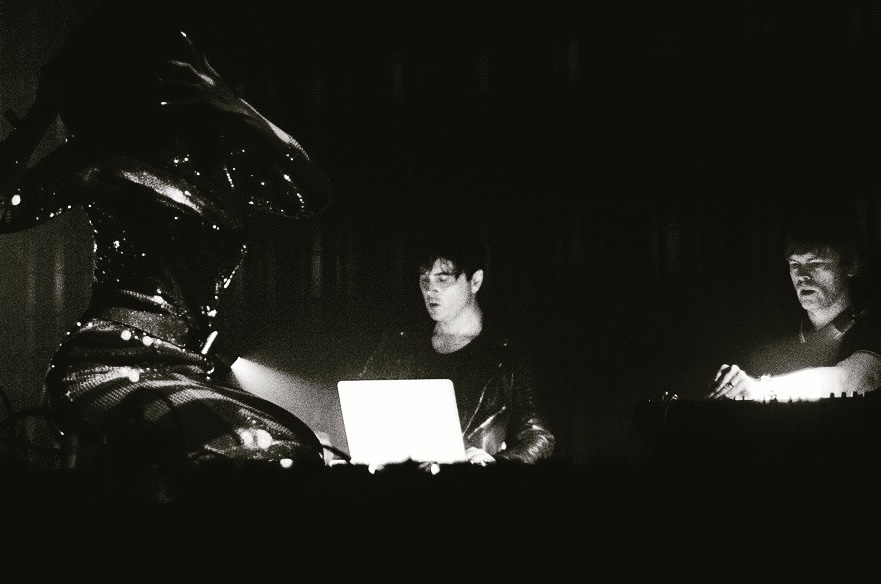

We’re sat, the four of us, in the moderately posh mezzanine lounge of a moderately posh downtown Detroit hotel. Kristen and I on one side of a large table, Child and O’Connor, two architects of the Birmingham sound – a blistering but surprisingly nuanced and slyly humorous subgenre of techno that Wikipedia gets “totally wrong” – on the other. Child is finishing up a hard-won salad as adult contemporary hits play on speakers nearby. We’re meant to be discussing their improbable, unexpected (and excellent) debut BMB LP, Active Agents And House Boys, but right now, we’re talking about Detroit techno – if and how it resonates with them, with BMB, within their respective, respected bodies of work. It’s early afternoon, and the third and final day of the annual Movement Electronic Music Festival is about to begin. British Murder Boys, “Britain’s best-loved, absurdist, space-rock duo,” are set to play at 7:00 PM. Their set will be heavy. It will be bracing. It will still be light out. O’Connor goes on:

“Of course, now I know that stuff is amazing. But it was erring on the side of pop, and I was in a different space then.”

“Underground Resistance, Jeff Mills, that kind of thing is definitely in my musical DNA,” says Child.

“I worked for John Loder at Southern in the late 80s, early 90s,” O’Connor recalls. “Eventually, this Interfisch record came in, but it was on this new label called Tresor. And it had this remix by Underground Resistance. Instantly I went, ‘This is absolutely amazing.’ After that, the UR records came out, and I couldn’t define why I liked them. I didn’t know if the people were Black or white. I had no understanding, but there was something there that hit me because it was danceable, but it was so completely far away from the stuff that Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson did.

“I think they were very much informed by European music.” O’Connor continues. “And they just did what British people always do. We take American music, repackage it, and give it back to America. They just did it the other way around, which is brilliant. They had this very heavy, European aesthetic, but applied their very Detroit thing to it. That’s what I loved about it – it was extremely hard. But all in a very natural way. It wasn’t forced or contrived.”

Nor is the racket BMB make, though in parallel to those early UR records, it’s difficult to grasp the whole of it straightaway, while simultaneously being relatively easy to describe when boiled down. One could reductively say, “Oh BMB are sick. It’s Regis on the mic over some massive Surgeon beats.” But that doesn’t give you the whole picture, BMB are practically the poster boys for Brian Eno’s beloved axis thinking – everything they do lives somewhere on multiple axes, positioned on multiple gradients between poles, genres, defined things. Nor does the above statement capture the subversive, countercultural mystique BMB have cultivated over two decades. Were it enough to do right by them, it wouldn’t seem so weirdly incongruous for the duo to be playing an expensive big-tent electronic music event that – arguably – caters to both influencer-adjacent club culture enthusiasts and rave nostalgists in equal measure. It’s easy to wonder how BMB fit in within the wider, aboveground club and techno ecosystems, how they square the circle?

“Personally, I do a lot of different projects and collaborations, and I think BMB is probably the project which is the furthest from techno,” says Child. “I find it hard to define what it is exactly. It’s a mixture of a whole lot of things, and there is techno in there, but it’s barely techno.”

“Because me and Tony are influenced by pre-techno stuff. I think we’re the last generation of people for whom that’s the case,” adds O’Connor. “We have no real interest in club culture. We came along when it was in its infancy. It was the wild west at that particular point. We’re informed by other stuff. I think there’s this golden thread about us that’s traceable back to Coil or Renegade Soundwave or Cabaret Voltaire or Throbbing Gristle. I think we’re in that lineage.”

“England’s Hidden Reverse,” offers Child.

“Yeah, and then Sleazy kind of gave us the name,” says O’Connor with a smirk.

“Well, he rubber-stamped it,” Child interjects.

“Oh, yes! I like that,” grins O’Connor, fingers tented, doing the best impression of Throbbing Gristle and Coil member Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson he can muster, before swiftly changing tack to the subject at hand:

“But big festivals like this – it’s just a place. And we’re contrarians as well. A lot of people wouldn’t do what we do on a big stage. It’s a chance to see what we can get away with. And it’s only an hour,” O’Connor laughs. “We can get away with it.”

“If there’s a tour involved,” Child notes, “a show like this is how we can get over here. That allows us to do other things where the budget is very different. At the end of the day, that’s how it is.”

“That’s not to reduce it just to stuff like that,” O’Connor counters. “We like presenting our music to people – even if they don’t like it.”

“This idea about performing on bigger stages,” adds Child, “I would hope that, even if it’s one or two people who never knew what we did, and were like, ‘Wow, what was that?’ Maybe it opens up a new musical world for them. I’ve had those kinds of moments where you see or hear something, and it somehow changes your universe. Those are important moments. I would like to think that might happen occasionally when we play big stage events.”

“This is also the first time we’ve done anything even sort of professionally,” O’Connor chimes in. “We’ve got an album that we’re promoting and some sort of tour as well. We’ve reached for something that we haven’t done before – some professional kind of thing.”

Talking to O’Connor and Child can at times be delightfully disorienting. They interrupt each other, threads are dropped and picked up again, sincerity might be punctuated with self-effacement, sarcasm, cynicism. That the two of them have very different personalities is a given, but together, a unified, off-kilter sense of humour and trickster energy is palpable. In conversation, BMB becomes “the nation’s heart” and they themselves are “national knick-knacks.” Could it be that, as a project, BMB is, at least in part, a piss-take? Or a cheeky middle finger to club culture as a whole?

“That’s possibly true,” says O’Connor. “It’s just in our nature.”

“What was it?”, asks Child. “Didn’t Luke [Turner] write something about how we’re not taking ourselves seriously, but we are also taking ourselves very seriously? Simultaneously?”

“Yeah, we don’t have a plan, but we know exactly what we’re doing,” answers O’Connor.

“There are a lot of paradoxes in BMB,” says Child.

“Which goes back to the wider club culture thing,” O’Connor adds. “We’ve nothing to do with it. Especially now that it’s just – it is what it is. It’s completely different.”

“You know, there are so many things that go into BMB,” offers Child. “It’s me and Karl. It’s our sense of humour. We didn’t grow up together, we didn’t go to school together. But for sure, if we had gone to the same school, we would not have been allowed to sit together.”

“Separated!”, exclaims O’Connor.

“Trouble, chaos, and destruction happens,” deadpans Child. “They would put us in different classes. Maybe move us to different schools. Something naughty happens when we get together.”

“It’s very naughty,” O’Connor echoes.

“We are huge, huge fans of stuff like the Bonzo Dog Band, Vivian Stanshall, all these kinds of things,” says Child. “All that stuff goes into BMB. To me, it’s funny how people go, ‘Oh yeah, industrial.’ Maybe there’s a bit of that in there, but it’s a tiny little part of it. There’s a lot more going on.”

“We don’t use the ‘I’ word,” notes O’Connor. “Especially in England. We don’t use that word. American industrial is completely different. Industrial is TG and the Cabs at a stretch and that’s it.

“But the way I grew up was very British-centric,” O’Connor continues. “All the bands that I loved were English. Very rarely did I like anything to do with America, to be honest. There was this sweet spot where everything was happening, and pop music was very subversive. You could have a pop band at number one who were friends with Coil.”

By now, it’s almost three and Movement is officially underway. The volume of our adult contempo soundtrack has crept up to compete with the increasing din of people filtering through the main floor lobby below. We’re talking about how the pop music industry has become almost unrecognisable as we’ve gotten older, when O’Connor reflects: “With the new album, there was talk about, ‘Oh, should we try to give it to a big label?’ I know a lot of people at a lot of these labels, and they just didn’t get it. Can’t see any value in it, anything to sell. I’m sort of happy about that, this deep into our career – I’m quite proud of it.”

“Probably the best thing with BMB is,” O’Connor continues, “it’s not that it lacks ambition, but there’s no way it could be commercial. And I think that’s okay, I think that’s good. Where a lot of things are now, you feel there’s a whole team behind people – everything’s so edited. But that’s accepted now.

“I went to see that Taylor Swift film with my daughter and all it was, was thighs and teeth. I could tell, every single second, that I was watching money going up and up – just money, money, money, money going up. But that’s the way the world goes on: choose the biggest thing.

“But the great thing was, at the end of the film, my daughter turned to me and said, ‘You know what? I really hate Taylor Swift.’ And she’d thought she was fantastic. She’s hated her ever since. So, job done.”

Child laughs. “There goes our collab, Karl. We’ve blown it.”

In the moderately posh mezzanine lounge of the moderately posh downtown Detroit hotel, someone who may or may not be Goldie is peering around the corner, and it’s become impossible to tell if the silky, seductive rhythms oozing from the speakers above are actually increasing in volume or simply becoming impossible to ignore. Either way, it seems prudent to steer the conversation back to the aforementioned debut BMB LP before our recorder’s microphone is swamped by some ‘Smooth Operator’ knockoff.

“Before we say anything about it, I’m interested in what you guys hear in it?”, Child asks us.

What do we hear in it? We hear an evolution. We hear less. Which is to say, compared to BMB’s previous work, Active Agents And House Boys feels more spacious. There’s more room for dubbier elements to come through. We hear a proper album – as opposed to a series of singles masquerading as an LP – one that ebbs and flows with ease, unwilling to ape the pedal-to-the-metal, full-throttle experience of BMB’s recent live gigs. We hear O’Connor, almost toasting, voice seemingly miles away, drenched in echo and reverb. We hear Child’s rough, rolling, roiling drums. Thunderous, like a soundsystem positioned just so in a cinderblock warehouse. We hear something undeniably different, but something that could only be BMB.

“It’s interesting you said ‘evolution’,” O’Connor responds. “Because the brave thing of it was reversing – or reducing – everything we’ve done before. People expected this very multilayered, very complex sort of record. But it’s a very, very raw dancehall record. In very many ways, it is reggae, it’s dub. It just came straightaway. And I know that’s the best thing, because we’ve really tried to do albums over the years.”

“Yeah, many times,” Child says. “There are folders on the desktop that say ‘BMB album 2010’ or whatever. We started many times and it just never turned into something.”

“It’s the weight of expectation, which was very difficult, really,” O’Connor offers. “But with this one, it’s what great art should be: you get it, warts and all. And you let it go. Like the first Sabbath album, you know? I think we were thinking the same thing: ‘If we’re gonna make this interesting for ourselves, let’s do something quick, and it can’t be laboured over.’ Because there’s so many great sound technicians out there, but there’s no real ideas in any of it. And you can tell it’s us. I think you can tell it’s us.”

“I agree,” Child affirms. “I wouldn’t call it a wild left turn, but it’s different levels of stuff that were already in our sound – some bits have been turned down, some bits have been turned up. It’s just a different balance of whatever we’ve always been.”

“Raw warehouse tracks in the spirit of things that we did years ago,” adds O’Connor.

“Yeah, it’s all laid down live,” says Child. “It’s just a live stereo recording. I sent it to Karl, and he was really excited. He did some vocals, and the whole thing came together.”

“We actually got each other’s energy,” O’Connor explains. “It’s all very well to sit down and write music. We don’t write music – we make music. It’s two completely different things altogether. It’s like Beefheart said, ‘I don’t read books, because books are straight lines that control. I think in circles.’ And we’re the same thing, you know. But the thing is, we need our energies to work together.”

“A lot of things lined up,” says Child. “We accidentally made an album, basically.”

“We were always aware of what not to do,” O’Connor says. “More than anything, the problem was we weren’t sure what to do – up until this point.”

“I think a lot of artists have that,” Child confirms. “You put out some music that has a significant impact, and then when you don’t do anything for a long time, it gets worse and worse, with people wanting you to do something. Like, ‘Can we have some more of that? We love that, can we have some more of that?’ That’s so opposite of what my whole idea of art is. We did that, and that was about then. And that made sense then. And that’s not who or where we are now. So, there’s no point. I literally couldn’t make more music like that. I can’t even remember how I did it!”

“That’s why we’re at odds with the scene, you see,” O’Connor says. “Everybody who makes dance music can go into the studio and make music for mass consumption, because they’re thinking of the commercial elements of it. Profiteering, where we obviously don’t do that. If we were clever – ”

“Making those tracks,” Child interjects, “there’s nothing else existing. It’s just us, in that track, banging it out.”

There’s something a bit perverse, a bit unhinged about O’Connor & Child releasing their debut BMB long-player some 21 years after their first single, more than a decade after they publicly “ended” the project in Tokyo, after they released three of the greatest live records of all time. It is decidedly counterintuitive, decidedly contrarian. Who was clamouring for this? Before this album was announced, the imminent downfall of capitalism seemed more likely than BMB releasing an LP. It was so off our radar, that we never even thought about it. So, how could we know that we wanted it? Let alone that we needed it?

“Do you know what? It’s the same for us,” says Child. “Literally, there was no plan to do it. We did a gig in Bristol, and we were like, ‘OK, we need to burn this down and start again.’ Out of that came these tracks. I think we’d probably given up the idea of making an album, and one just kind of appeared out of nowhere.”

“We did give up,” O’Connor agrees. “We were happy doing what we’re doing, and it was good. There was just something weird about that weekend in Bristol. We just felt, ‘What can we do?’ There were all these things that conspired. Remember, the hotel was so cold that week? Sleeping in my all my clothes. It was weird.”

“So weird,” echoes Child. “It was a good gig, but it kind of agitated us a bit – a grit in the oyster sort of situation.”

“But you’re quite right,” O’Connor concludes. “Nobody needed [the record].”

“We’re all in agreement on that,” Child confirms.

“It’s probably not what people wanted, either,” says O’Connor, grinning. “But it’s what they’re going to get.”

“People will make of it what they will,” Child says, “and I don’t care if they love it or hate it.”

“We’re quite lucky,” O’Connor notes. “We’re not just two people who made a record and put it out there. We’ve built up a lot of good faith over the years with our music – a lot of bad faith as well!”

“I just love the thing Karl said – quite a long time ago, actually – about being able to disappoint even our closest fans,” says Child as we get ready to go. “We’re still capable of disappointing.”