On March 20, 2020, three days before the coronavirus lockdown began in Britain – and as the rest of the world, if it hadn’t already, prepared for restrictions – brothers Roger and Brian Eno released Mixing Colours, their first collaborative album together, on Deutsche Grammophon.

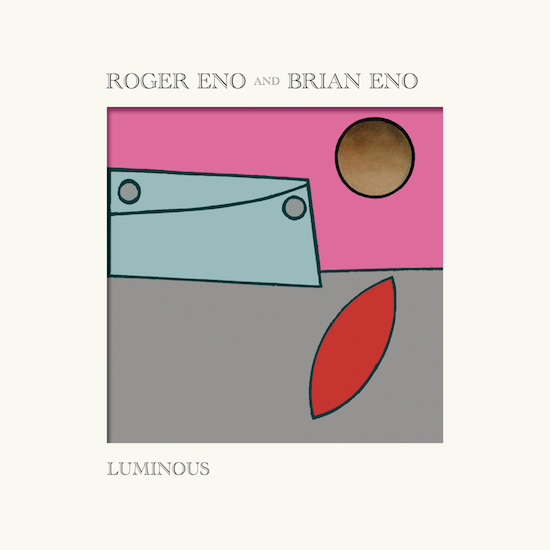

Some three months later, as the virus continued to cause havoc with global health and economies, and as they prepared for the release of an associated mini album, Luminous, on 14th August, the Brothers Eno took questions from tQ about their ongoing collaborations and the state of our post-virus world, both today and in the future…

The 18 pieces that make up the original Mixing Colours album are often poignant, always beautiful, sometimes a little disconcerting, but distinguished, even at their more abstract, by a strong sense of melody. Do you consider them to be, ‘ambient’ music, for example, or ‘classical’ music, or have these terms become ambiguous and indistinct over the years?

Brian Eno: For me the idea of ambient music was as much about the way we listen as the music we actually make. Ambient music suggests a stillness and receptiveness in the listening process, a different set of expectations about what music is supposed to do. I wanted Ambient to mean ‘a music without a clear distinction between foreground and background’ and ‘a music without clear beginning or end’. Removing those boundary conditions from the music opens it up to a kind of mental wandering, a sort of exploratory walk through a field of sound. In some senses, then, this album isn’t strictly speaking an Ambient record – the pieces are sonically distinct, have beginnings and endings – but nonetheless the listening style derives from ambient music.

One of the pleasures of palliative music like this has been the room it leaves to let the mind wander. Giving each track the name of a specific colour, though, casts it in a certain light, and I’ve seen reviews in which writers have striven to justify the connection between title and music, so I’m curious as to how much time and consideration you gave to these titles, and how significant you think titles are in shaping how we hear a piece of music?

BE: I like the phrase ‘palliative music’. When there are no lyrics, titles become very important! The title becomes the only indication of what the composer thought the music was about. In our case, we didn’t want to give – couldn’t give – very clear directions in that respect, so we chose deliberately vague titles. You could think of each piece as a sonic colour palette as much as it is a melody. I think by choosing these names we were saying, ‘Don’t try to attach narratives to these – listen to them in the same way you might look at an abstract painting.’

Do you prefer to think of music as functional or magical, and can they be both at once?

BE: For me the function is to be magical. One of the great mysteries of life is that we can so easily be affected at an emotional level by the arrangement of a few tones or a few lines or a few words. It’s astonishing how sensitive to those things we are.

I remember – quite clearly – the first time I saw a Mondrian painting. It was a reproduction about 10 centimetres square. I was ten or 12 years old. I was knocked out – entranced, amazed – by the picture, which was one of his archetypal three colour works, but I was even more knocked out by the fact that something so minimal could affect me so much. I have never lost that sense of astonishment: why are we sensitive to art at all, and why are we so tuned in to these tiny differences? If a Martian came to Earth and you played her a late Beethoven String Quartet and then another written by a first-year music student, it is unlikely that she would a) understand what the point of listening to them was at all, and b) be able to distinguish between them.

What this makes clear is that most of the listening experience is constructed in our heads. The ‘beauty’ we hear in a piece of music isn’t something intrinsic and immutable – like, say, the atomic weight of a metal is intrinsic – but is a product of our perception interacting with that group of sounds in a particular historical context. You hear the music in relation to all the other experiences you’ve had of listening to music, not in a vacuum. This piece you are listening to right now is the latest sentence in a lifelong conversation you’ve been having. What you are hearing is the way it differs from, or conforms to, the rest of that experience. The magic is in our alertness to novelty, our attraction to familiarity, and the alchemy between the two.

The idea that music is somehow eternal, outside of our interaction with it, is easily disproven. When I lived for a few months in Bangkok I went to the Chinese Opera, just because it was such a mystery to me. I had no idea what the other people in the audience were getting excited by. Sometimes they’d all leap up from their chairs and cheer and clap at a point that, to me, was effectively identical to every other point in the performance. I didn’t understand the language, and didn’t know what the conversation had been up to that point. There could be no magic other than the cheap thrill of exoticism.

So those poor deluded missionaries who dragged gramophones into darkest Africa because they thought the experience of listening to Bach would somehow ‘civilise the natives’ were wrong in just about every way possible: in thinking that ‘the natives’ were uncivilised, in not recognising that they had their own music, and in assuming that our Western music was culturally detachable and transplantable – that it somehow carried within it the seeds of civilisation. This cultural arrogance has been attached to classical music ever since it lost its primacy as the popular centre of the Western musical universe, as though the soundtrack of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the 19th Century was somehow automatically universal and superior.

Anyway, as I said at the start, to be magical is to perform an important function: it reminds us that value is something we create and we confer onto things. We make value. We are the magicians. It isn’t ‘outside’ us – it’s a result of the cultural ecosystem generating meanings, and it’s our minds that are the key players there, not a particular set of marks on a page or grooves on a disc.

It was a peculiar quirk of fate that saw Mixing Colours released when it was. Obviously you wouldn’t have asked for such circumstances, but, as the Corona situation developed, did they make the album’s release feel especially poignant and necessary? Have you had any feedback that has particularly touched you? And would it be stretching things to suggest that, in a sense, you provided a public service by releasing it when you did?

BE: This kind of music says: ‘Sit still, listen, surrender, be open to the moment. Nothing much is going to happen, and that might be just what you need right now.’ I always liked that line from the Talking Heads’ song: “Heaven is a place where nothing ever happens”. And I always liked the idea of going to a club where, instead of getting stimulated and all revved up, you instead get calmed down and find some space to think and feel. That is surely one of the things we want from art – the chance to be in a different world, or in a different version of this world.

In a situation where there isn’t so much to do – the situation we’ve all been in for the last few months – there are two broad choices. The first is to invent new things to do, like cooking sourdough bread or making TikTok videos or training our pets to knit sweaters. The second is to get to a point of enjoying not having much to do.

It was indeed a fortunate coincidence that Mixing Colours appeared just as the virus made itself manifest. I can assure you it wasn’t part of the marketing campaign! A lot of people have said they found it a great comfort in these past months, and I have to say that I did too.

Though we’ve all been worrying about health issues the last months, I’d argue that the extra mental space some of us have enjoyed – admittedly perhaps the more privileged of us – has been a blessing. Certainly, during the early part of lockdown, one thing I heard said by a number of people with whom I talked was that, in truth, they were secretly enjoying the opportunity to slow down and feel themselves free of the usual daily social obligations. Did you, too, share that feeling, and do you think it will be possible – and even appealing – to maintain a slower pace of life once this is all over?

BE: It is an act of resistance that we all need to make. What is it we are resisting? Being turned into obedient modules in the military/ industrial/ pharmaceutical/ entertainment complex. We have to stop just buying all this shit that is being produced to keep us working and spending. We have to stop being cogs in the machine; a machine that doesn’t serve any of our interests except the few people who are becoming obscenely rich from it. I was talking the other day to a carpenter who lives nearby. He was astonished by how little money he’d been spending over the last months because there were no shops open. It had changed all his perceptions about how much he needed to earn, about what he really liked doing. He’d discovered he enjoyed being with his children by the river…

As for the social effects: it’s been so nice seeing people having an alibi to be nice to each other. England has been through five years of division and anger. Now something has happened that allows us to reach across and say ‘Are you OK?’

Equally, it’s very clear to see that the macho divisive authoritarianism that runs through so many governments now – UK, Brazil, Hungary, USA and so on – has proven completely unable to meet a serious challenge like coronavirus. The places that dealt with it well have a much more – dare I say – ambient approach to government. That’s to say, a diffuse, responsive, non-teleological style of government more attuned to caring than winning. Many of those governments are led by women, for whom nurturing and maintaining an ecology of social relationships seems more important than a competition between alpha males. This is about devolving power, wealth and political and social participation through the whole of society rather than putting it all in the hands of the ‘big men’.

Why do you think that those who shared this sentiment – one which some friends described as relief – also felt guilty about enjoying this slowdown, and almost dreaded a return to normality?

BE: Don’t feel guilty! Feel empowered. It’s a humanly costly way to become empowered, for sure, but it’s all we’ve got right now. This is the chance you’ve been waiting for, a chance to change your mind and direction. it might be the last chance we’ll get.

It feels as though the last few months have provided an opportunity to look at the world around us in more detail than we have for years, even as we weren’t allowed out to see it. What we recognised, it appears, was upsetting – from institutional racism to political hypocrisy to capitalist greed – and enough to rouse people from their seats even in a pandemic. Why do you think that we seem more alert to injustice and inequality at this particular moment? Do you feel hopeful about the possibility of change, or do you fear we will settle back into old routines, forced to do so by ‘the system’?

BE: This is an interesting question. Are we more alert to injustice when we have the time to be? I think the answer must be yes. If you’re working hard all day to get some food on the table, trapped on the treadmill of consumerism, there just isn’t much time or energy left to care about anybody else’s life. Suddenly there’s a lot of time, time to read and watch and see what is going on around us, and be appalled by where we’ve got to, how far we’ve drifted from what we hoped for. And along with that comes the realisation that we are much more fragile than we thought: that a little strand of RNA can knock the whole planet off course. That new sense of fragility produces two other feelings: ‘Who is in charge here?’ – it clearly isn’t the politicians – and ‘Why are some people so much more exposed than others, how did things get so catastrophically unequal?’

I hope something new grows out of all this. The only viable future now depends on us acting as an intelligent species, cooperating on facing up to shared challenges – climate change, pandemics, tax evasion, corruption – and creating societies in which everybody has a stake, and thus an interest in preserving and building the society rather than destroying it. We have to include everybody! I have started thinking about the various anti-discrimination movements – BLM, feminism, LGBTQ, etc – as pro-inclusion movements. I think that is a better way of naming them – saying that they are for a new type of inclusive world rather than saying what they are against. The Left has always tended to describe itself in negative terms – in terms of what it was against – rather than in terms of what it was for.

There will be enormous commercial pressure to get back on the treadmill – so many peoples’ businesses depend on it – but at the same time I see a distinct drift away from those free-market values as people rediscover their own ingenuity and creativity. And as they do that, they start to take responsibility for this planet and for the welfare of all the creatures on it, because, as the astronaut Rusty Schweickart once said: “We’re not the passengers. We’re the crew."

There’s something warmly nostalgic about Mixing Colours. I put this down to the fact that it harks back to simpler times. Do you recognise that nostalgia I find in there, and what do you think is responsible for that?

BE: I think this has something to do with melancholy. Roger and I have talked about this in the past, about the difference between melancholia and sadness. My feeling is that melancholia is a sort of bittersweet pleasure in the thought of how things could have been, or how they could be now if only things had turned out a bit differently. My friend Peter Schmidt used to say that one of the functions of art was to offer the possibility of a more desirable reality. Some people dismiss this as ‘escapism’, but I think that isn’t a fair criticism. Surely we improve our worlds by imagining others that are better? And the kind of art that is called escapist is a sort of compass bearing for what ‘better’ means.

As for nostalgia: isn’t that ‘the pleasure in re-experiencing something in our minds that is no longer available to us’? Isn’t that a way of digesting past experience, of returning to it in your mind and finding what it was that you liked and wanted and still need from it? We are all living in fast-changing worlds that we have to keep adapting to, and it’s natural that we scan our past experience for clues as to what might be the best ways of living. When I lived in New York for five years I became increasingly aware that I wanted to make a kind of art that gave me a place to get lost, to be alone in a wilder, less populated place which was not controllable. I made the album On Land to be able to access that place.

Given that further lockdowns seem inevitable, what have you learned these last three months – whether from circumstances or from making music – that might be useful to those who have struggled with the situation?

BE: 1) I enjoy my own company.

2) I don’t mind having time on my hands.

3) I like simple things – like a bike ride with my brother and a friend – or alone.

4) Boredom is fruitful.

5) We’re the crew, not the passengers.

You announced the launch of A Quiet Scene, in which you invited people to submit videos of their post-lockdown world, at the end of April. The website suggests that, within just two months, you’d had almost 1,750 submissions. Were you surprised by the volume of offerings?

BE: We were surprised by both the volume and the quality of the results. There was such a lot to look at. It made me feel proud of our audience! That seems like a strange thing to say, but I felt ‘I’m glad that people of this creative level enjoy our work.’ Imagine if the opposite had been the case, that we’d been inundated in really bad videos. That would have been pretty disappointing and may have made me reconsider my whole life…

The taste for this kind of mood – slow, quiet, meditative – used to be marginal but now, I’m happy to say, there are quite a lot of people at that margin. To me that signifies the emergence of a new type of mind, a type of mind we need in this new type of world. It’s a kind of minimalism, a sense that ‘this will be enough for me’ and ‘more isn’t necessarily better’, both of which are good and appropriate anti-consumerist messages, but it’s also an acknowledgement of the power of the individual mind to create its own value rather than have somebody else push their version of value down your throat. Perhaps this represents a quiet revolution in human awareness.

These pieces exist the way they do because of MIDI and the infinite possibilities that this allows in terms of (for want of a better word) ‘manipulation’, something underlined by the fact that ‘Spring Frost’, ‘Verdigris’ and ‘Cerulean Blue’ all have their origins in the same recording. How does one decide that something is finished, or is that concept of completion something of an illusion?

Roger Eno: The writer, or the composer, of the piece can decide when he or she feels that the piece is finished, but this does not necessarily make it so, as it then goes into another’s hands, or ears. This means that it can be used in thousands of different ways, most simply thought of in terms of ‘film’ music, perhaps. In this case a piece of music ‘under’ an image can become quite a different thing: it has been added to – or, when poorly placed, subtracted from – and thus was not finished after all. The piece also can be re-arranged: some of the pieces on Mixing Colours would make great carillon pieces – imagine them ringing out over Antwerp or Ghent – or played by a wind octet or ice cream vans…

These changes also bring into question when, if ever, a piece is finished. I rather like the idea of a piece continuing to evolve as I’ve only limited interest in the ‘Great Composer’ idea. I sometimes prefer a less organised, somewhat more ‘democratic’ approach.

Roger, which was greater: a sense of relief in letting these pieces go and not feeling responsible for their final incarnation, or a fear of what might happen to them once you’d passed them on to Brian?

RE: I had no qualms whatsoever about handing my pieces over to my brother as I knew he would only add to them. I’ve known his work and working methods for years, and have admired both greatly. I also know my own strengths and weaknesses and felt – rightly, it turned out – that we would complement each other. My great strengths are an intuitive sense of melody, an ability to create a strong mood with very few elements, and a love of often very simple harmony. My weaknesses are that I do not pursue any genuine idea of ‘production’, and this can leave my music sounding rather naked and, possibly, rather archaic. This, oddly, is what I often strive for. I like the idea of black and white ‘sketches’ that simply begin, do something for a bit, and then stop. I’m not fan of ‘development’ and fiddliness. So, in Mixing Colours, I sent Brian such sketches and he ‘coloured them in’ as this is one of his great strengths: that of post-production. One of my favourite pieces on the album – I won’t tell you the name – was taken by him and reversed. This is something I would not have done, yet is a masterstroke. Lastly, I do ‘feel responsible for their final incarnation’. It’s just that, with these ‘children’, there was another parent around…

Have you ever considered making these pieces available in their original shape, and just how much transformation would we perceive between what you, Roger, first sent to Brian and what then emerged once Brian had done his work?

RE: I have handwritten the piano scores of the entire album and intend to use these in my live performances. Without Brian’s input, they are skeletal, sparse things with a rather stark quality to them. What I’d rather like to do is to badger my brother into coming onstage with me, him treating the pieces live as I play. I already utilise Dom Theobald’s artworks as ‘Foredrops’ in my live work, so it could be splendid to go the whole way. I could also arrange them with instruction for other groups of players, encouraging them to ‘bend the pieces’ – add bars, lengthen notes, put in silences etc – so that each performance is unique. This, once again, is getting away from the rather prescriptive intentions of ‘The Composer’.

Can we expect you to continue working together like this, and, if so – given that neither of you seems to restrict yourself to a single realm of music – can we expect something significantly different in the future?

RE: I’ve barely played piano for two months or so, but have found it all but impossible to put down the melodeon, a diatonic accordion. I’m considering a solo release for next year using perhaps a small choir, or maybe just four voices, a harmonium, and assorted ‘unusual’ instruments: the melodeon is great for drones and simple chords, and I own a portable harmonium. I live in an area of England that is dotted with medieval churches, each with its own natural acoustic. I’m thinking about recording in such places to incorporate the sonic quality of the (sometimes) 900-year-old structures as an instrument in its own right. Also bells… you can hit it with a stick, but you can’t beat a bell…

Roger Eno and Brian Eno’s Luminous EP is released on vinyl on 14 August and Mixing Colours Expanded is released on CD on 23 October