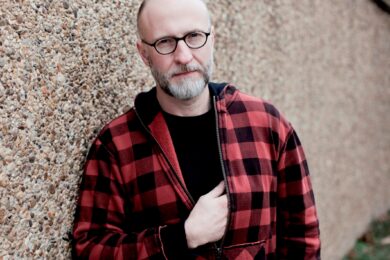

Though undoubtedly one of rock’s most industrious individuals, guitarist, vocalist and songwriter Bob Mould’s workhorse ethic is combined with a rare innovation. He pioneered a fuzzed-out, psychedelic strain of melodic punk with 80s hardcore heroes Husker Du, thereby laying the foundations for what would, later become indie rock. In the 90s, he assembled Sugar, a new three piece with bass player David Barbe and drummer Malcolm Travis, which witnessed a further refinement of his noise & melody aesthetic and birthed one of the greatest and most underrated guitar rock albums of all time, 1993’s concise, uncompromising Beaster. He’s also one of the few openly gay musicians to have emerged from the early 80s hardcore scene, having come out in 1994, at a time when few musicians were prepared to be open about their sexual identities.

In the periods following the disbandment of Husker Du and Sugar respectively, Mould has busied himself with a remarkably varied solo career which has taken in Richard Thompson-influenced folk rock (1989’s bright, approachable Workbook and 1990’s excoriating, cathartic Black Sheets Of Rain), soul-baring power pop (1996’s underrated post-Sugar effort, Bob Mould) and forays into electronic indie pop (2002’s Modulate and its sister album Long Playing Grooves) which predated the huge success of not entirely dissimilar-sounding outfits such as The Postal Service and Cut Copy. This pair of off-road experiments also played a major part in the foundation of Mould’s well-attended Blowoff club nights, in which he and fellow DJ Richard Morel play progressive house and techno (plus a smattering of contemporary electropop) to a predominantly older, gay crowd. In recent years, Mould has also revealed himself as something of a hottie – once a fairly glum looking dude, he’s currently looking buff, tanned and ridiculously healthy.

Released 30 years since the formation of Husker Du, Mould’s new album for ANTI records, Life And Times, is a keeper, displaying the musician’s undying knack for hooks and emotionally involving narratives of heartbreak and redemption. He will be showcasing this new material plus songs spanning his illustrious career this Wednesday May 6 at the 02 Academy in Islington, London.

Life And Times is lovely. I’m a big fan of Sugar and that’s the era of your songwriting it most reminds me of.

Bob Mould: “Oh really? Thanks!”

The album is being touted as something of a song-cycle. How accurate is this?

BM: “Well, the record is a couple different things to me. Songwriting-wise, yeah, I mean, they’re all autobiographical to a degree, but the last couple of records I’ve been framing in this blend of autobiographical and observational. Which I think is sort of what life is like for me and for all of us. Sometimes I’m writing from experience, sometimes I’m writing about things I’ve overheard somewhere that make me think about experience, there’s a certain amount of literary creativity in there where it doesn’t really apply to me at all, yet I’m the one who’s thinking of it. There’s always that part of it. Y’know, stylistically, this one… I was surprised when you mentioned Sugar, I mean, songs four, five, seven, eight, yeah, but the first three, which I wrote in order about a year and a half ago, when I wrote those I felt like I was revisiting Workbook, which came out in ’89. That was the first record after Husker Du. In 1988 I spent a lot of time woodshedding and songwriting, and I came upon this style where I was writing a lot of free verse and narrative poetry, collecting thoughts and putting them all on a piece of paper, then improvising music to the words, not necessarily dealing with the words in sequence. I was doing that a fair amount, especially with the song ‘Life And Times’, that’s like about five different periods of time that I can think of, that those words were written in. I love that style, the more acoustic feel, that was what Workbook was to me. And this record, coming out twenty years later, it’s a little bit of a revisiting of that. Then the middle stretch, as you pointed out, the heavier guitar stuff, is more in that Sugar category I guess.”

I’m interested by what you say about not needing to live the song. As a sex writer, a lot of people think that means I have every experience I write about, which is really funny because it’s part-fantasy, part-experience, part-other people’s fantasies, part-other people’s fears, part-conversations I hear on the bus, or in bars or whatever. I think people don’t imagine that songwriting is fiction writing either.

BM: “Yeah. It’s not a literal start-to-finish narrative, like a book where there are nine chapters then the dream sequence where the credits roll… but having said that, it is a little bit. I mean, to me, I’m about albums, and if you wanna call that a song-cycle… I grew up on Beatles albums, Who albums, jukebox singles, I grew up with that history of music where albums were these 30 or 40 minute statements. They were concise and they were song-cycles in the sense that they captured a feeling, they captured a moment in time, they weren’t assemblages of loose pieces, they were very much like, you sat down and conceptualised a record and what you wanted to say. I still carry that with me to this day, that’s like my operating mode, and I hate dragging albums out to 70 minutes just because I can. I like making a concise statement and having everything relate in terms of key and tone and feel, I really try to lay the records out to have psychology, to create feelings for the listener as an entire piece of work.”

That’s interesting – so for you the psychology of an album is about more than just the lyrical content, it’s about feel too – and about what you leave out as well as what you put in?

BM: “Well with this record and the cutting out, there were two songs that didn’t make it that were great ROCK songs, really aggressive, real strong playing, and the words didn’t carry the weight that the rest of the record had, and had I included the two songs there would have been a few people who were like, ‘Man, those are the rock songs we’ve been looking for!’ but it would have thrown the whole balance of the record off. And they’re great songs but they didn’t have the right feel, so those might be a good launchpad for another project.”

My impression was that although the songs were about loss and uncertainty, musically they seemed very finished, quite satisfying. So there’s a sense in which the music is saying, ‘This is a story, I’m putting some distance between myself and the narrator of the lyric.’

“Hmm, well, that’s funny. The methodology of the recording is this – I do everything at home now, and a lot of this stuff is just first thing in the morning stuff. A lot of what you hear is me writing the song. I don’t labour these vocals, I don’t labour these guitar parts. There’s a lot of mistakes in there. A fair amount of the stuff is the first time that I’m doing it. A lot of the playing, I’m just coming up with this stuff on the fly.”

Wow. Okay!

BM: “Yeah, that’s the beauty of working at home. The curse of it is, well, when am I finished? [laughs] Nothing ever seems completely finished. But satisfying, yeah, there’s an essence to it, a sort of purity to it, that I enjoy because I don’t shine all the rough edges off of everything. There’s a lot of compositional… those are compositional guitars, first thing in the morning vocals and if there’s four bad notes I just get the Autotune out and fix them. I’m not gonna sing it again because I know when the mistake is and I’ll probably make the same mistake every time I go by [laughs]. I just go for the natural feel and that gives off an effect, psychologically, I think. It gives it all a feel and as far as distance, well, like a song like ‘The Breach’, it’s so quietly sung… there’s a technical term in recording for when you’re too close to a microphone, it’s called the proximity effect, and it’s sort of unpleasant to the ear, but it’s on that vocal and I left it there because I wanted people to, I wanted it to feel as though I was right up on somebody’s ear. And it’s… at least in my mind that’s what I was trying to do with it.”

Sugar ‘Tilted’

I’m interested in what you say about biography. The temptation with songs about heartbreak is that people try to look for the identification, isn’t it?

BM: “I think traditionally in pop music, or in song and story in general, that’s… what people want. They want to personalise these stories and make them their own via the creator or the vessel. It’s a funny relationship because I don’t like the idea of demystifying it, because it’s nice that there are still some people that believe in the power and the magic. Y’know? Sometimes taking it apart is… I don’t wanna deflate the balloon for anybody ’cause I love when I hear a song and I feel like it’s speaking to my core and that the people singing it understands exactly what I’m going through. That’s what we’ve done for centuries.”

When you look at someone like PJ Harvey, I think a lot of people assume that because of her narratives about pain and heartbreak, it was easy at first to look at this young, frail woman and think, OK, she’s had all these experiences. And the biographical element early on became almost a kind of extension of the sexism women have to deal with in the industry. Is there a similar prurience in the way the press treat you, as a gay man?

BM: “Oddly no. I don’t think I have to deal with that. And I agree with what you said about PJ Harvey, I think that speaks a lot about the power of the early works, that people want her to project and want her to portray like that. But as a gay man, no, I don’t…. I think there are certain facets of the press that want to associate my sexuality with the work but I think the vast majority are trying to associate the work with the body of work I created before, and that’s a different kind of story to explain [laughs]. I’ve got this big body of work that things are constantly compared to. I think that’s the one that I have to contend to each time out, comparisons with previous works that they’ve elevated already. I try not to think about that too much [laughs].”

The notion of classicism in music has become a weight for everybody hasn’t it? In terms of guitar music, we’re in a kind of retrogressive stage, where classicism has become a really heavy burden on a lot of people, and the idea that there was a sort of golden age of indie is perpetuated in a lot of independent culture now, which I think is not necessarily helpful.

BM: “Yeah, I agree with all of that. The good news is that good music always wins and the records, the music that was always important to people, that continues to live on. You take the good with the bad on that, we all do as fans and we do as creators. It’s a burden to have an acclaimed body of work, but… y’know, that’s what we want [laughs]. We never get the complete deal. You gotta pay a little bit on each side.”

Husker Du has more weight on it than most, though, being seen as the bridge between hardcore and what eventually became indie. It happened at that kind of crux moment.

“Yeah, it’s a band everyone speaks of in pretty big terms. For me, I find it a little differently because I’ve been there and I’ve done a lot of different things since. That was a great time and a great place to start making music, and the environment was right for that kind of music. Um, all the weight that has been attached to it since, it used to drag me down a lot, because it made it harder for me to feel like I was progressing and growing because everybody always wanted to hold me to that weight, and now I laugh about it because I should be so lucky to have weight around [laughs].”

But I can see why it would be difficult, being judged by this standard that isn’t even necessarily self-imposed. You might want to expand away from that.

BM: “Yeah, and I spent a fair amount of time and a lot of effort trying to do that at the beginning of this decade. Y’know, Modulate, the electronic record, I put a lot of work into it, it was sort of like learning how to do something in public, I might have been better off working with a producer on something like that…”

I really like Modulate!

BM: “I do too, but I can look back on it honestly and say, ‘Yeah, if I’d had a little bit of help from somebody on that, it would have been a hundred times better.’ But I wanted to do that for myself and I did it in public and it really caught a lot of people off guard. I like that record a lot too.”

Bob Mould ‘Sunset Safety Glass’

I wanted to ask about Modulate and also your secondary career as a techno DJ. I wondered whether it was a ‘gesture’ album… because with Workbook, there was such a feeling of exhalation, for me, that I imagined had to do with the end of Husker Du and finally getting to work on solo material that might have been waiting. I got a similar sense with Modulate, that maybe this was something that had been around for a while.

BM: “Yeah.. it was what I like to call a hard reset. I was trying to re-invent, trying to shake the language that was familiar to me. I think all of us that create, from time to time, we need to shuffle the deck so hard that you’re bound to create something incredible or something that you really need to refine and shape a different way. Modulate was a big chance, and I think had I not done that, I wouldn’t be where I am now. My love of electronic music that started in ’99 got me to making that record and got me to start Blow Off, the DJing nights that we do. I had just moved to DC, I didn’t know anybody, I met Rich Morel, my work partner in Blow Off, we started to write songs together, we started this DJ night because I wanted to make friends, and here we are six years later and I’m probably doing better in that, as far as sheer attendance numbers, than I am in my regular career. In the context of this article it might be secondary, but for me, it’s… we’ve got fifteen events in the first half of the year!”

Husker Du ‘Makes No Sense At All’

I was interviewing Juan from (joyful Californian avant-punk band) Abe Vigoda, and we talked about cultural identity and the bearing it has on music making, and he told me that you were his gay guitar hero, when there were like, no gay guitar heroes. On a related note, I’ve got a quote here that says ‘Argos’ was written for your theoretical gay punk band. So who’s in the band, why don’t they exist and why are there no gay guys working in independent/DIY music?

BM: “Well, the Abe Vigoda guys are great, I think that must have been right before they came to DC and played and we hung out and had a really good time. They’re really sweet guys. As far as my gay theoretical punk rock band, that’s me and my four friends, and it’s an in-joke really. One guy was trying to learn how to play guitar, another guy actually knows how to play keyboards and write songs, but he was never gonna get around to it, another guy moved here from Chicago and he’s a really good musician, so we joked that we were gonna have this band and we weren’t gonna have any songs longer than two minutes long and they were all gonna be these gay punk rock meets Kraftwerk kind of songs. And I wrote one song, and… we haven’t done anything since! All my friends are gay, I just can’t get them to do anything! It was sort of a running joke for last summer. So anyway that song was part of the joke, then I realised it was really a cool song so I put it on the record [laughs]. So that’s how that came about.”

So, back to the question of why there aren’t more out gay men in independent/DIY music…

BM: “Y’know, that’s a good question.”

Because in my experience there just aren’t many. My best friend has been working in DIY music for the last eight years, he’s out, and it’s lonely. DIY is what he sees as his culture and it’s not that it’s not accepting, because it is, but it’s just not somewhere where there are a lot of out gay men working.

BM: “Well, I think there’s a number of different ways to look at gay culture. There’s the kind that we see in American gay TV, you know, like Queer As Folk, where it’s all clubby and sort of druggy maybe, there’s that part of it, and then there’s the parts that are sort of more camp-oriented and the parts that are sort of bear-oriented, then there’s like ‘normal’ people who don’t identify with any of it. Where songwriters and stuff fit in, I don’t know. I’m gonna say this out loud and I know I’m gonna get shouted at for it, but when did gay people start having such bad taste in music? Didn’t we used to be the leaders and the tastemakers? Then maybe about ten years ago… what happened?”

What happened to Queercore as well, the punk strategising, and why isn’t there more interesting cerebral queer electronica like the kind you’re promoting with Blow Off?

BM: “I really don’t know. Maybe as far as out indie DIY musicians, maybe it’s just not a field that gay musicians gravitate to, I don’t know. It’s a really good question, I don’t know if I have a good answer. I don’t think there’s a bias against it, I think people in their 20s are really not hung up on that any more.”

I don’t think it’s because the scene isn’t accepting, in certain places it really is, it’s just something that for some reason… it’s not a strategy for making art that especially gay men seem to gravitate towards.

BM: “Well how about this for an idea; if people are self-identifying as queer musicians, do you think that perhaps by doing that, they’ve already eliminated part of the audience at large, therefore they’re not as noticeable as, say, Bright Eyes or whatever?”

Maybe. That’s certainly possible. I was involved in a recent discussion about (feminist-identified music event) Ladyfest, and about feminist culture, which was the most cool thing about Riot Grrl, the diversity, all kind of different cultural identities were involved early on. But the music very quickly gravitated towards punk and let itself be dismissed by virtue of being, you know, ‘incompetent’, snotty, refusing to engage with the press, and as a strategy it didn’t work. It’s such a difficult balance because I can see why punk as a strategy seemed inclusive, but it’s still highly exclusive in some respects.

BM: “But the thing is that early punk and even early hardcore, it was very inclusive because anybody could do it as long as they had something to offer. And I think that, at that time, it crossed… there was no sexual boundary to it. All the people involved were outsiders, whether they were LGBT or not. That was a space where everybody could create. That was my experience from back then, I didn’t sense any strict sexual guidelines, I mean, we were just coming off a very androgynous period with glam rock, so I think people on the punk side were very tolerant because everything else was just hair bands, jocks and metalheads and stuff, and they weren’t gonna sit there!”

That’s interesting, because when you watch Riot Grrl documentaries they all talk about how exclusively male early hardcore was.

BM: “Um, that might be so. That I can’t really argue with when I flash back on it. I know in Minneapolis there were a lot of girls around, both gay and straight, inside the scene, but still the majority of it was guys. Yeah. Especially as hardcore became this ritual dance, with the moshpit and that really sort of severe neo-military look, the jarhead-ish kind of look. Then it became sort of a parody of itself. Like, by ’85 or so it was pretty ridiculous as well.”

Was there a time that you felt people were perceiving you as a queer artist first and foremost?

BM: “I think I always wanted to be seen as a musician and a songwriter first because that was my trade in life. I mean, in ’94 after I was professionally out, I never really thought about it, to be honest. By then, I don’t know if I was in denial or if I had just assimilated the thoughts in my mind, but now I’m like… when I write ‘Argos’ I’m guessing Joe and Jenny in Stillwater, Oklahoma aren’t really gonna understand a song about a gay bath house, or a gay bar that has a dark room. Like, ‘Oh honey, let’s play this at our wedding!’”

Well you’d be surprised…

[Bob laughs uproariously]

I say that because I used to listen to a lot of dub, reggae and dancehall, but I didn’t really understand Jamaican patois all that well. So I would create my own narratives and would happily sing along syllabically with some really homophobic songs without getting what they were about at all. I really liked this one song, ‘Limb By Limb’, which is by Cutty Ranks, which is a hideously violent incitement to murder of gay men, really detailed about the violence too, and I happily imagined it was about him going on tour and taking over all the towns, killing it every night…

BM: “Oh no!”

I loved it. I sang it every day. I put it on mixtapes for friends of mine and they were all like, ‘What the FUCK?’

BM: “Oh no!” [hysterics]

So you never know, maybe Joe and Jenny are singing along to ‘Argos’ thinking, ‘This is about a really great party where everyone can be free!’

BM: “You never know. Oh, man, that’s wild. Oh gosh!" [more laughter]