A couple of months ago I received a surprise parcel of second-hand books through the post from a friend who I hardly ever see. There were four of them: On The Side Of The Angels – the second volume of the journals of Elizabeth Smart; The KLF: Chaos, Magic And The Band Who Burnt A Million Pounds by John Higgs, Liars In Love by Richard Yates, and The Importance Of Music To Girls by Lavinia Greenlaw. Upon receipt, I had read none of them, but I began with the latter, and the bulk of my reading of it was serendipitously soundtracked by a revisiting of London band BOB’s 1991 album, Leave The Straight Life Behind, which was given a well-deserved reissue in a considerably fleshed-out capacity earlier this year.

The Importance Of Music To Girls is a stubbornly unclassifiable first-person account of growing up as a teenager in 1970s and 80s Essex; part straight-down-the-line memoir of adolescence, part critical analysis of the intersections of pop, punk, and disco in this seminal period, part poetic paean to the deep emotional connections we forge with the various cultural artefacts which scaffold our stumbling towards adulthood. Greenlaw’s text is a celebratory, distinctly British document of a life defined and sculpted by the music which, incrementally during these years, seeped out of radios, black and white TVs, and sketchy live venues dotted around London and its extremities. In tone and texture the book (not to mention the way it found its way to me) made for a good narrative companion to the repeated hours spent in BOB’s company via the re-release of Leave The Straight Life Behind, which buffers the original album with welcome live and session recordings, including the three Peel sessions the band completed over the years.

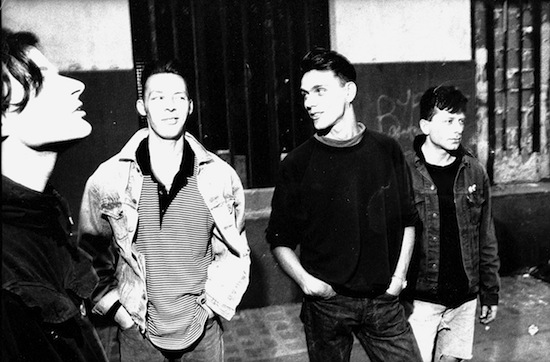

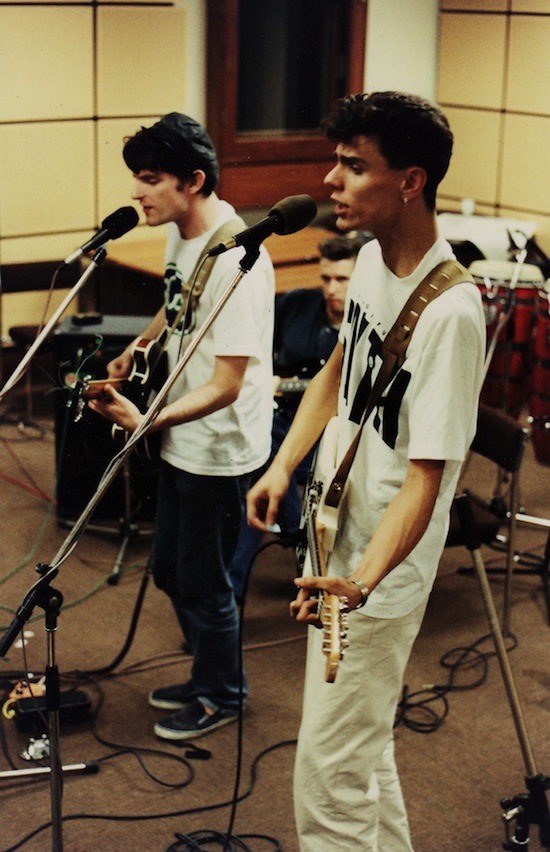

The kind of band BOB were renders the inclusion of the latter more than appropriate; in many ways Richard Blackborow, Simon Armstrong, Jem Morris, and, later, Dean Leggett and Simon Hersom, together formed one incarnation of that multifaceted phenomenon: a ‘definitive’ Peel band. In its melodic range and inclination, use of layered vocals, and earnest lyrical tilt, BOB’s music – heartfelt, alternately abrasive and emotional indie-pop which, despite sounding unmistakeably British (sharing much of their sound with Postcard bands like Josef K and Orange Juice), also ploughed a similar path as Australia’s The Go-Betweens, and even – dare I say it – Aussie/NZ outfit Crowded House (who formed across the oceans in 1985, the same year as BOB). As such, it had Peel written all over it, and, as it happened, the influential DJ played an active and pivotal role in shaping BOB’s path. But more of that later.

The way that package of books was sent – bound up in a re-used jiffy bag, with a scrawled postcard of greeting and enthusiasm, and even several tiny boxes of moribund Scooby-Doo candy sticks (yep, the fake-ciggy ones which seem wildly anachronistic now) occasioned a nostalgic rush for a time when people actually sent you books (and yes, sweets) through the post; when the latter was still one of the main arteries of communication and connection. It’s a time described by The Importance Of Music To Girls and also by Leave The Straight Life Behind; listening is a specifically evocative experience; the sound of a Britain and a London which in the late 1980s was formed for many by those things which happened on its edges, its peripheries.

Formed by Blackborow and Armstrong from the bones of a sixth form college band, BOB waded out without a particular set of co-ordinates, recording insular demos in Blackborow’s older brother’s home-built studio, before very gradually discovering connections with, and tapping into, the increasingly vital underground London indie scene of the late 1980s. As these connections became welded, the band (with pivotal line-up changes and additions) realised itself and embarked on a prolific and undeniably noteworthy career through those legendarily fecund years for the British counterculture, carving out an untrammelled space for themselves which resonates to this day.

1986 single ‘Convenience’; an unabashedly lovelorn, jubilant heart-renderer which wouldn’t be out of place on You Can’t Hide Your Love Forever, has for many still never been topped in terms of its sheer conviction, tunefulness, and emotional delicacy.

I spoke to Blackborow recently, and – predictably given the tenor of his music – he proved to be a singularly articulate, gentlemanly sort, espousing that blend of humility and self-assurance regarding the import of what he and his bandmates did which made for a rewarding exchange. Now living in Cornwall where he continues, in his home studio, to work both on his own music and with new artists (at the time of our conversation he was wrapped up in producing an EP for a writer friend who had just experienced an awful loss, and wanted to memorialise that loss in a musical as well as textual way), Blackborow is evidently perennially creative, having maintained a quiet productivity in that vein since his band split in 1995.

I was curious about that name, for starters: "For a while we were ‘Beasts Of Boredom’, until we found that there was an American band called ‘Beasts Of Bourbon’. So we abbreviated it to B.O.B. for a while, but quickly got fed up with being asked what it stood for. Hence, BOB. Just a meaningless name, we thought, and friendly! We put that name on the [first release] flexi, thinking that we could still change it if we thought of something better. Peel playing the flexi meant that the name stuck. We grew to like it." (Blackborow sent me an addendum which specifies that the name be capitalised at all times; a stipulation I find appealing, hinting as it does at that middle-ground between self-deprecation and a seriousness about what you are about; a space occupied by many of the artists I love).

You’ve just reissued BOB’s only long-player, Leave The Straight Life Behind, more than 20 years after its original release. Can you just tell me a bit about why this is happening? Is it something you’ve been wanting to do for a while?

"When BOB finished there was a 10 year period in which I really didn’t want anything to do with it! Mostly because there were other things I wanted to do. When I was 30 I went off and did a degree…and then ended up moving down here [Cornwall]. There was talk about a BOB re-issue prior to my leaving London about 10 years ago, and I did kinda start putting things together, having had overtures of sorts (minor ones!) from various small labels. But it just never quite happened. And then when I moved down to Cornwall I actually became quite heavily involved with new music projects, and the plans for BOB took a backseat. But the plans were always there."

The collapse of the distribution arm of Rough Trade in the late 1980s/early 1990s, which propelled the label into bankruptcy and receivership, went some way to claiming BOB’s Leave The Straight Life Behind among its many casualties. Having spent years muddling their way through in expressly independent fashion, spurred by what one senses is a natural work ethic and effortlessly creative disposition on the part of Blackborow and his bandmates, the eventual point at which their debut coalesced and was released coincided with Rough Trade’s demise, curtailing its reach considerably.

"When we first got together it felt a bit like an… explosion of creativity and we wrote A LOT. We were moving and changing quite quickly at the same time as being quite stubbornly independent, and not particularly organised in terms of management and things like that. So there were a few years prior to 1991 where there were actual chances to get the album together, but we didn’t get it off the ground. By the time we actually thought, ‘Bloody hell, we need to do something about this and actually make a record!’ It actually resulted in a pretty frustrating situation. We’d been touring for three years, had a number of singles out, but still ended up having to finance [the album] ourselves. But we finally made the record, were really happy with it – and excited – and then of course the whole Rough Trade thing happened…"

Leave The Straight Life Behind actually sold pretty well in its initial run, enough to necessitate a re-press; but, because of the circumstances, it was a re-press that never happened. Blackborow ruefully remembers the vague absurdity of the situation: "So then we were touring the album (we toured a lot), and we had all these people coming up to us at the shows saying, ‘I want to buy it, but I can’t find it anywhere.’"

There have been a lot of re-issues from the era in question recently, which has precipitated a degree of eye-rolling in some corners. However, given the particularities of BOB’s case, there is a sense in which the re-release of Leave The Straight Life Behind seems not only valid but vital; a document of hard work and love which, due to the vagaries of a particularly volatile independent sector in the late 1980s perhaps didn’t reach as many of those people who would have fallen for it as it should have done.

Hard work and love were bound up in BOB’s beginnings: teenage pals Blackborow and [Simon] Armstrong and started early and with conviction: "Simon and I had a band together when we were in the sixth form, and we loved it even though we hadn’t got very far with it at that point. When the time came to leave school, the four of us who were in the band decided to take a ‘gap’ year, pursue the band and ‘make it’, I think really believing that would happen…

"But, in reality, this schoolboy band carried on for a year after we left school…and it was actually pretty crap, and we didn’t get anywhere. Realising this, at the end of the year the other two guys wanted to go to college. Simon and I, on the other hand still had ambition, I guess…so we deferred [our college places], and put together BOB…

"It was just the two of us to start with, Simon and I writing and demoing like crazy. We were very close but also very different; in the previous band I’d been the drummer and he’d been the singer/frontman. I guess because I’d started writing a lot of songs I’d become frustrated with the set-up in the previous band. As a result, when Simon and I got BOB together we both agreed we’d both sing and we’d both write songs…"

And so BOB was born. Blackborow and Armstrong both began writing at a prolific rate ("it was healthily competitive"). A system soon developed in which the pair made use of the capriciousness of Blackborow’s elder brother: "We were lucky. My brother had a cottage in the west country, and he’d built an 8-track studio in the attic – for himself – but then he promptly fucked off to America so it was just sitting there empty… and I could go there whenever I liked. So, Simon and I would stay in London for two or three weeks, write four or five songs each, and then we’d head down to the west country to record demos."

The pair worked diligently in this fashion for a good year or so before BOB really got going: "We built up a huge number of songs, and actually became competent at writing. And in knowing how to record what we had written."

They also started their own label – House Of Teeth – in order to self-release. In 1986, and with bassist Jem Morris and a drum machine, BOB put out an unabashedly lo-fi three-song flex ("We realised a flexi was only an extra £100, and would be more likely to be played by a record company or DJ") including the contagiously chipper ‘Brian Wilson’s Bed’ ("It’s the perfect camouflage/ for an old boy with less soul than the Wigan Casino"). Finding themselves armed with "boxes and boxes of these things", the band went off to see if they could persuade Rough Trade to take a batch off their hands to sell on the shop counter for 50p, a mission which resulted in a serendipitous encounter:

"Simon was talking to the guy at the counter, and part of the negotiations involved the guy playing one of the flexis to see if it was any good, and just at that moment Peel strolled into the shop and proceeded to rummage through the stacks with one ear cocked and obviously listening to the track. When it finished he walked right up to Simon and said, ‘Can I have a copy of that? I’d like to play it on my radio show.’ Obviously Simon gave him a copy, and then ran back to mine, and we set up the radio and cassette recorder….and waited…"

And he played it that night?

"Yeah! he played it that night – two of the songs, which was even more gratifying!"

Peel always seemed to gather these kind of anecdotes round him, testament to the way he went about things; playing songs twice or two tracks back-to-back, this quality of excessive passion…

"Exactly- that kind of spontaneity, and also this sense of following stuff through, keeping promises… I guess he just had a very open mind; a genuine, unshakeable enthusiasm…"

That first kept promise was just the beginning. Not long after Peel’s discovery of BOB, Blackborow was sat at home when the phone rang. At the end of the line was the man himself (Blackborow’s home telephone number had been on the back of the flexi), telling him they’d had a cancellation for a session and wondering of BOB would be prepared to step in and do one in 3 days time.

"Simon and I agreed that at that point most of our ambitions had been more or less met… we hadn’t really ever thought of anything beyond that!"

The resulting Peel session heralded something of a game-change for the band. Blacborow and Armstrong were aware of the C86 phenomenon without feeling necessarily affiliated with it. ("We were really in our own little world – I don’t think either of us were aware of any particular scene happening; it was just the two of us drawing on the things we liked.") However, the release and exposure via Peel soon saw BOB initiated into a London live circuit which Blacborow perceives as being revitalised in the wake of the now legendary/notorious NME cassette. Discovering kinship with- and playing alongside – a slew of similarly-minded bands like The Siddeleys, Reserve, and Jessie Garon & the Desperadoes, BOB soon found a (temporary) home with Sombrero records, the label behind a lot of the live shows they fell in with. A brief stint with drummer Gary Connors segued into the recruitment of Jamie Wednesday’s Dean Legget, a man with unrivalled energy and ambition and, apparently, an address book to match. And, so equipped and defined, BOB seemed by 1987 to have properly realised themselves, going on (with, sometime later, bassist Simon Hersom in lieu of Morris’ departure) to carve out the remarkable legacy of songs which constitute the meat of this reissue.

And many of those songs are irresistible and a delight to revisit. Whilst not included here, it’s safe to say that the aforementioned ‘Convenience’ single – probably the best-known of their tracks (making Peel’s Festive Fifty), and marked by the kind of wry earnestness the more bookish bands of this period pulled off so well. ("I have seen lights turn green/ just for her convenience/ that girl has an unbelievable smile.") In many ways sets the template for the lion’s share of this high-energy album. The predominant impression is one of light and richness, a surging, restless jangle-pop which trades on a pithy turn of phrase and an arch self-deprecatory tone (‘Take Take Take’ somehow gets away with the shocker, "Too much masturbation/ too much hope, and too much beer" by way of its knowing delivery). The title track sounds like Biff Bang Pow doing The Razorcuts – or maybe the other way round – and it’s as much of an upbeat treat as that might suggest.

The reissue reminds, however, that there was a slab of darkness and grit bumping along behind BOB’s singalong sunshine, demonstrated in album opener ‘Dynamite’, which is moody, mournfully angry, and characterised by a slanted lyricism as, "I throw my life in your face/ I hope that you choke on the taste/ looking back/ and moving on." Similarly, ‘Skylark II’, wrapped in a distorted sample of The Shipping Forecast (there’s that radio again), counters a plaintive, elegiac vocal verse with a suddenly expulsive power-pop chorus brimming jealousy and reproach.

Blackborow talks about his band with great affection and warmth, and narrates a recognisable tale of self-discovery and self-definition, through music and friendship and hard work: "By the end of the first year [in BOB] I was happy, I felt we’d achieved everything I had hoped to. But then I guess sometimes things take on their own momentum, and you start thinking, "Oh, maybe we could do this as well, maybe we should try to do that…"

And they did; a career marked out by an authentic DIY approach which is emphatically manifest in their determination to get this reissue out there, and ensure a representative document of those achievements exist. BOB and the body of songs represented by Leave The Straight Life Behind will have inflected many lives back when the band were still a live proposition, or bleeding out of the radio on heavy rotation, and for them – and for the band themselves ("looking back/ and moving on") – this reissue will undoubtedly be a thing to treasure. For the rest of us, it offers a welcome window into what now feels like a very different time in the history of British independent music, and a chance to flesh out our picture of that time with the work of a band who very much deserve to be part of it. At least, we can all now get our hands on a copy of the album.