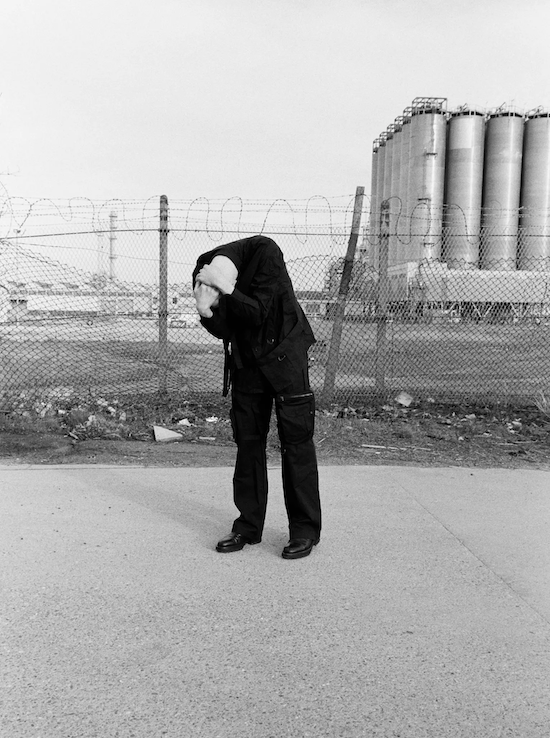

Photos by Timon Benson

The records of Blackhaine – the project of Salford-based multidisciplinary artist Tom Heyes – reveal a world of paranoia, grit and desolation. Pairing brutal choreography with a muscular, elastic take on UK drill, he constantly throws us back into the same scenes: lurking the streets of Salford, holed up in anonymous hotels, or blasting through sheets of late-night rain on the M6.

These records are also bound, just as compellingly, by constant references to violence through a lens of detachment. From street crime to narcotic self-destruction, the violence in Blackhaine’s music is broadly presented as meaningless or superficial. “I got tired of listening to the same overly aggressive stuff all the time” he explains with a smile. “I wanted to put a more boring take on it.”

While boredom is a valuable theme in Blackhaine’s work, his three EPs to date – 2020’s Armour, 2021’s And Salford Falls Apart and 2022’s Armour II – are works of tremendous vitality, insight and dynamism. Characterised by sudden shifts between thumping drill and ambient noise, created with producer Rainy Miller, Blackhaine’s music explores class, mortality, addiction and ennui: his aggressive rapping style slipping into plaintive chanting and earnest confessional.

An equally unusual choreographer (having notably been invited by Kanye West to work on the Donda listening events), Blackhaine’s performances draw from butoh: a form of Japanese dance theatre in which performers twist their bodies in ways that can be physically punishing. Taking additional reference from seeing spice smokers bent involuntarily shapes in city centres, his contortions reflect how his music – tough and muscular as it might seem – can suddenly snap pliably in new directions.

Blackhaine describes his latest record Armour II as a sequel-of-sorts to Armour, picking up the former’s narrative device of a car journey (seen in Armour highlight ‘Black Lights On The M6’) to present “a car crash in slow motion”. Employing more melodic arrangements and guest appearances than Armour, this record’s increased dynamism helps articulate the rapper’s shifting train of thought. This reaches its conclusion in ‘Waiting Room’: the beat cuts out, and Blackhaine’s rapping crescendos to a breakneck, hyper-aggressive verse he describes to me as “ultimately meaningless”. After a silence, the EP’s final minutes are instead given to a gorgeous piano outro: guest-vocalist Kinsey Lloyd arrives to “save the day”, as Blackhaine explains, in an epilogue-of-sorts calling for listeners to come together. While Blackhaine’s music makes powerful use of aggression, it never equates aggression itself with real power. Ahead of his performance at WOS Festival in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, Blackhaine discusses the world-building across his records to date.

While both Armour and Armour II are replete with images of being in a car barreling forwards, the music itself makes constant deviations – marked by changes in structure, texture and speed. Could you tell me about the role of car journeys in these records?

Blackhaine: I’ve always seen the car thing as about creating containers, from which I can view the outside. In terms of the pacing, it’s more about what would happen while I was in the car that would change how I see the outside, as opposed to the speed of the journey itself. My thoughts, I suppose, are amplified when you create this container of the car.

You always seem to be riding in the car rather than driving it. In ‘Blackpool’ on Armour you’re “riding through the moors, you see me riding in this car”. In ‘Stained Materials’ on Armour II you’re “in the passenger seat”, and in the videos for both ‘Stained Materials’ and ‘Armour Freestyle’ you’re shown in the back of the car. Could you expand on this?

B: That’s an idea I’ve not really unpacked. I suppose it’s just that when I’ve written about car journeys, from a historical perspective, I’ve been too inebriated to drive myself, or just getting ferried about – which happens a lot in my life nowadays.

Your claim in Armour II-opener ‘Stained Materials’, “I could’ve been something” which is then repeated in ‘Pavement’, complements your claim in Armour-opener ‘Blackpool’ that “I don’t even know how the fuck to be someone”. It’s also revisited when you claim you “never even had dreams” in Armour II closer ‘Waiting Room’. What can you tell me about the role of aspiration in your music?

B: I think what I’ve wanted to do with my music, in a sense, is this ‘failed gangster’ thing. I grew up listening to this road rap that’s super aggressive and angry; I remember being in this meeting years ago and someone telling me that when we’re angry we’re trying to mask a need. It’s kind of alluding to that Marlon Brando scene where he says “I could’ve been a contender”: I’m trying to do that same ‘washed up hard-man’ thing.

When I wrote ‘Blackpool’, that was before I learned how to build a world – it was more about my personal feelings in those moments. As I’ve started to deposit stuff into a world, to save myself I suppose, I’ve turned it to be like ‘I had it but now I’ve lost it’. I think there’s something quite tragic about that. When there are aggressive moments in my music, or even my performances, it always comes from a shallow place.

Religion takes more prominence in Armour II than in your previous work. Touched upon in ‘Prayer’ and ‘Faith’, it takes centre stage in ‘Waiting Room’ when Kinsey Lloyd delivers a eulogy calling for the listeners to come together and asks “what does faith mean to you?” Why did you decide to emphasise this religious element in Armour II?

B: If Armour was lurking around in the ends in a car, Armour II is a car-crash in slow motion. I think we’ve all had moments where we’ve thought ‘this might not end up alright’ – I’m not a religious person really, but religion’s something you jump to.

A collaboration I found particularly exciting on Armour II was Iceboy Violet and Blood Orange teaming up for ‘Prayer’. How did this come together, and what do you see this as having contributed to the record?

B: I wanted to invite more voices, so it’s not just one point of view. I’m happy to have my voice challenged on my own record to push the narrative further. Even though I didn’t give Iceboy much direction, they took my verse and amplified it.

Your music offers interesting explorations of class, and you’ve indicated that your art’s focus on deconstruction – from deconstructive choreography to music deconstructing established genre tropes – points to the need for structural change in society. What can you tell me about this interest in deconstruction, and its relevance to political discourse in your records?

B: In UK dance, the whole class thing is very apparent. To be anything other than middle class or above that is quite hard – some of the guys that run these organisations are on a quarter million a year.

The Arts Council runs the world of dancing in the UK. They need a social capital return on everything they do, so it becomes centred on weird ideas sometimes – I just got angry with it and decided to do my own thing. I just wanted to create more of a level playing field, because there’s boss, boss kids out there that just don’t really get a good chance because they don’t want to play the game.

With music, I’ve always had the benefit of the fact that people around me are good at doing their own thing. Politically, it annoys me how experimental music is seen as a middle-class thing. I’m not going to sit here and say it’s not fair, but there’s disadvantages everywhere.

Dehumanisation or violence towards human bodies is a motif in your lyrics, extending to how your choreography twists your body into punishing, unnatural positions. It can also be seen to influence projects like your 2020 film nothing urgent, surreal or of meaning, in which you feed lyrics through a voice automator to dehumanise them. What role do you see this as serving in your art?

B: It’s trying to fight the idea of being numb. A lot of the reason my music’s so aggressive is because I was trying to force myself to feel something. I definitely live a healthier life now. One of the themes in the Blackhaine world is how ‘the thrill is gone’. In that film, it’s supposed to be boring – I just wanted to create a feeling of being numb, something you can tap in and out of. There’s moments in my music that are more aggressive: it’s me trying to break through that feeling of being numb, before it subsides to boredom again.

Your choreography background draws heavily from butoh, contorting your body into shapes that have tested your limits. How do you see this as relating to your music, and how have your physical performances developed now you’ve been doing this for a couple of years and, I imagine, your body has experienced changes from the regular strain you place it under?

B: There’s a whole thing about deterioration that’s always there. Nowadays I try to make sure I’m a lot more prepared physically for my shows. I used to just go on and see what happened – now I have more of a plan, and I’ve started to eke in the physicality a lot more. It’s getting fun. Because it’s a physical thing and it’s sincerely impulsive, though I can never really put it into words properly. It’s beyond words.

How do you approach your shows, and what would you like to imagine people taking away from them?

B: I like to curate something different in terms of the lighting and setlist for every venue. I’ll even change the lights or setlist during the performance – I can kind of read how the audience is taking it. The rest of the lineup also affects things: sometimes they’ll put me on a night with noise acts, sometimes hip hop acts, sometimes DJs. Then again, there’s a certain element of wanting to challenge that, and push things a bit further. I do always like to start with ‘Saddleworth’ though, just as it means a lot to me.

How do you see your work as developing from here?

B: At the moment the newer stuff’s sounding way beyond anything I’ve done before – mainly because I’ve taken more time with it. There’s more live elements going into it: we’re recording guitars, live percussion, and we’ve already started looking at people for a band. It’s sounding fucking good.

Blackhaine performs as part of WOS festival in Santiago De Compostella, Spain, which takes place September 8-11. Tickets, the full lineup and more information can be found <a href=" https://workonsunday.es/festival/” target="out">here