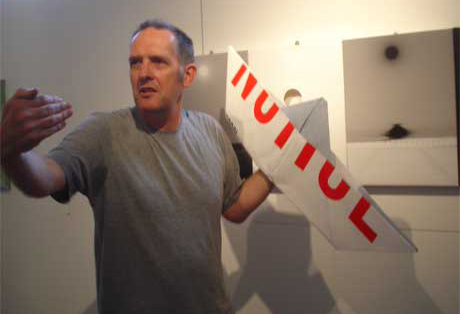

A couple of weeks ago, I was lucky enough to get to take part in situationist/artist/writer Bill Drummond’s new project; a choir called The 17. It was part of an occultish happening in the distinctly un-occult surroundings of a West London studio. I sat with 16 others – mainly people I didn’t know – drinking red wine listening to Drummond’s warm brogue explaining why he thought recorded music had run its course. His reasoning – compelling, flawed, exciting – ran that as a medium the age of the album was over. And then it was time to record ‘the piece’. This involved us singing all five notes of the pentatonic scale – for five minutes each. Then his affable sound man John stuck all the notes together on his laptop and played the piece back to audible gasps from the participants. (Jimmy Martin’s account of the night can be read here.)

Earlier this month his book 17 was published. It traces a bizarre and picaresque journey which he sees as a valediction to the album and the relevance of the 20th Century practice of recording music. It seemed like a good time to meet up with him and chew the fat.

The Quietus: I was quite drunk when I took part in The 17.

Bill Drummond: There was a lot of red wine round that night.

The Quietus: I wish I’d got slightly less drunk but it was still obvious that it was something quite special. Has the amount of times you’ve participated yourself diluted the experience?

Bill: Well, there’s nothing like the first time, ok? The first time, which was in Stockholm, it was just a relief because up until then it had just existed in my head and there I was performing it with an audience and it worked. And over the two and a half years I have become more critical and have become more aware of the tell tale signs that it is going wrong. There is a group dynamic and within five minutes it can drop by half a tone. Or it can all go up by the end of the five minutes.

The Quietus: Does that happen if you have one dominant voice?

Bill: It can just be the group dynamic or it can be if there is one dominant voice. I need to be careful when I say this but there has been one dominant voice who has done it more than once who is way off key but it is part of the making of it.

The Quietus: What would you say to accusations that you’re just being curmudgeonly, that there are plenty of people for who recorded music hasn’t run its course. That you don’t have to be a subscriber to WIRE magazine just to hear stuff that you haven’t heard before.

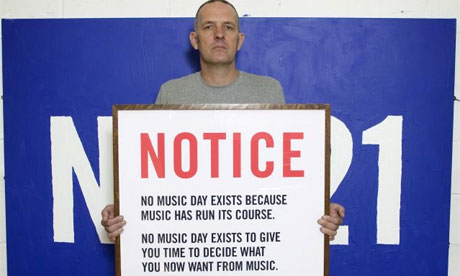

Bill: I would be very defensive on the accusation of being curmudgeonly because I’m not one of those people who think it was all better in my day and I’m not saying that there isn’t still good stuff being recorded out there. But what I am saying is that recorded music as a whole is part of the 20th Century. It has run its course. As a medium it is dead. If there is a 17-year-old discovering pop music for the first time then that’s fine, I can’t criticize what they’re getting from this. But over the coming years more and more people and I don’t just mean people my age, will realize that recorded music has run its course and that the whole thing is very restrictive. This thing that has been around since whenever is a very restrictive way of making, reproducing and appreciating music.

The Quietus: Have you heard of other people setting up their own choirs?

Bill: No. The 17 is my own way of reacting to this – I don’t think it’s the future of music. It’s too specific a thing to me. I state at the beginning of the book that part of it is throwing down a gauntlet to people.

The Quietus: Me and my friend Manish came up with this idea that there should be a prohibition of music, where bands were not allowed to record an album for five years but then everyone was made to release an album on the same day at the end of the period. It would be a great leveller and clear away some of the deadwood.

Bill: Look. Forget albums. Released music, forget it. You’re still thinking in this mindset. You’re still thinking of music as something you get on an album. A band are producers who make an album. That is what has ended. We come from an age where we know what an album is. We can appreciate it took something to make it, the artwork, the packaging etc. Then came CDs and already it seemed like the game was up but now with MP3s . . . It would be alright to have a moratorium but then to release an album at the end of it would be to miss the point. If you do that – then what’s the point of having the moratorium?

The Quietus: Like a lot of people you seemed to like the idea of the internet and peer to peer file sharing systems as a means of propagating music when you first encountered them. Do you see it more as the great leveller now?

Bill: Brilliant, yes brilliant at first because for the first time ever, recorded music immediately had no financial value. Again albums had a certain financial value, they were proper things that had been properly made you could see how much they cost to make but then CDs came along and we accepted it but after a while we used to see them given away free with magazines and newspapers and we knew they had no value. Then it had no visible value at all, you couldn’t see what had gone into it. Once that goes then you can see the industry struggling to keep hold of it, inventing new laws in an attempt to stop the inevitable. There have been loads of times in history when something has been very expensive because it is controlled by the few. Say for example the spice trade. Once spices were very expensive but now you can go into loads of shops down this road and buy whatever spice you want for less than a quid.

The Quietus: A bit like the invention of the printing press?

Bill: Yes.

The Quietus: So do peer to peer file sharing systems mean we will return to a pre-World War II culture of having localized scenes and less fame for musicians? Was the post war boom in pop music merely a blip?

Bill: Things will never return to how they were before. Things never do. We have the internet so music can’t become localized but maybe we have seen the end of the internationally famous rock star.

The Quietus: You’ve said quite a few times that you’ve no interest in numerology but you’re obviously obsessed with numbers to a certain degree what with The 17, 45 and so on . . . are you constructing your own belief system around numbers?

Bill: I like numbers. They have a flavour, almost like colours do. With the KLF we were obsessed with the number 23 because I’d read about The Illuminati when I was 17 and that carried on into what me and Jimmy did but it was almost by accident. I’m obsessed with prime numbers as well but I have never ever read about numerology. I find numbers intriguing.

The Quietus: How long do you see The 17 carrying on for? How will it culminate?

Bill: For some time yet. Maybe another few years. I don’t know how it will culminate but maybe there will be a point where it is time to hand on the baton to someone else.

The Quietus: Something struck me while I was reading the book and that was you seem to self-deprecating about how high or low art what you do is but yet you sometimes describe yourself as an artist . . . Are you an artist or . . .

Bill: . . . a chancer? Age 17 I got asked to leave school and I didn’t know what I wanted to do so I went to careers advice and did all these test questions. I was good at drawing, so I did some paintings and I went up to Liverpool to try and get into art college and from the age of 17 to 20-odd I just read books on the subject. I never wanted to be a rock star or whatever but I read all about art and everything I have done since then has been informed by that. So as much as I hate saying it, that is what I am. I never wanted to be a writer. I know I write books but I never approach it as a writer.

The Quietus: Well in that case would you say that Francis Fukyama’s idea that liberal capitalism has won from his assertion The End Of History can be applied to art as a whole as well as you applying to this to music?

Bill: It’s interesting – it is something that interests me but not enough to make me actually read The End Of History! But music hasn’t run its course – recorded music has run its course. Music as a whole cannot run its course and art cannot run its course either. As a medium recorded music has run its course in the same way that certain forms of art that were very popular in the 20th Century have run their course. You will always get people coming along saying that ‘No, no, painting still has more life left in it.’ But really they mean that there is still money left in it because people still want paintings to hang on their walls. So some people will still do some interesting things with paintings but that is not really where the ideas are. That is not where the emotions are happening. So painting has run it’s course but art hasn’t. Really the possibilities are endless when you have a canvass but after a while you just start seeing a painting. With a recording the possibilities are endless but after a while you start hearing just another album. And there is so much more to art than painting by numbers.

The Quietus: So you think there is still room for the Francis Bacon of multi-media installations to make himself known?

Bill: Well, whatever, but you’re just looking at this from the cliched point of view of ‘multi-media installation’. Sometimes art is a cathode ray tube, sometimes it’s a piece of plastic. It’s part of our condition. We have to do it.

The Quietus: I’m on dodgy territory here and I don’t mean this as some kind of backhanded diss or anything like that. Despite the fact it’s peripheral to what you both do, I think you and Julian Cope are two of the best music writers this country has produced. Do you both share a common purpose or character?

Bill: I think we do loads. The things we have in common are: I have spent most of my life living in the countryside as he has. I’m not at the moment which is because of my family situation but this is not my natural habitat. I’ve always had an interest from a very early age in the pre-history of the British Isles. Now I’ve never made it part of my career like Julian has. We’re both drawn to writing. One major difference between us is that I’ve never been drawn to drugs. They were never a big part of my life. And I’ve never been interested in the iconography of the rock star. I may have looked at a picture of Jack Kerouac when I was young but I was never obsessed with Jim Morrison or whoever. I really like the way that Julian ploughs his own furrow. He has his own ideas and follows them. Most bands have a manager or record label boss and once they’re gone they’re finished but not him.

The Quietus: We ran a piece on The Quietus recently about how you got arrested with David Stubbs and Jimmy Cauty while doing a piece for the Melody Maker and you talk in the book about having a good idea about ‘The 17’ after spending a night in the cells. Have you been arrested a lot of times, and which was the most memorable occasion?

Bill: Yeah, I’ve been arrested a lot of times. I couldn’t tell you how many times. The biggest, the most important for me was in Liverpool when I was quite young. I was certainly very naive. The police arrested me for something that I won’t go into but it had nothing to do with me. ‘That’s it for you’ they told me. They told me I was going to go to jail for five years. I didn’t know that the police couldn’t send me to jail. I didn’t realise they didn’t have that power and that it was only a judge who could do that. All I was worried about was what I was going to tell my mum. But then some evidence turned up that suggested that it was these other two blokes who the police had been after for ages and then suddenly I was their best mate because they wanted information off me against these other two. I learned a lot from that experience.

The Quietus: Did you not find it daunting – the prospect of sitting down to write a book which was ostensibly based around a piece of music that you couldn’t, or rather wouldn’t, describe?

Bill: No because I knew I wanted to get everything out about music that I wanted to and then I’d never have to face it again.

The Quietus: As we speak at this very moment, Gary Glitter [Timelords/KLF collaborator]will be getting off the plane from South East Asia. What was your reaction when you first found out that he had been arrested.

Bill: Well, I speak as a father of three. He’s just got out of prison but . . . he will really be in prison for the rest of his life. He’s always been in prison in a certain way. The prison of his persona. How does he get back from this? He can’t. There’s no way back from this. He has committed the worst crime that can possibly be committed. It wouldn’t have been the worst crime ever committed 100 years ago and it won’t be again in the future but right now it is. Look at Oscar Wilde 100-years ago. Everyone was scandalized. They said he would never be able to come back – and he couldn’t. I’m getting myself into trouble here. It’s bad, of course it’s bad but because I knew him as a person I feel sorry for him you know. I liked him. He wasn’t the kind of person you’d want to spend any amount of time with him – too intense. Monstrously egotistical. I think he thought he was like David Bowie or Freddie Mercury. He thought he was a genius but he wasn’t. He was a throw back. An entertainer. A variety performer. Yeah but I don’t know how you deal with that. How do you deal with that?

The Quietus: I went to go up to Jura once. I nearly made it but just missed the ferry. I was going up with my mate and we thought we go to George Orwell’s cottage and burn a fiver each.

Bill: Well, we didn’t burn the million quid at George Orwell’s cottage, that was at the boathouse. People think Jura is this tiny island but it’s massive and really hard to get across. There was no logic to the location, we could have chosen anywhere really. We were originally going to do it up a mountain because we thought it would be dramatic. But then it started raining and we changed out minds.

17 is out now on Beautiful Books. It features, in his own words: “Music, Uncertainty, Bill Drummond, night trains across Russia, girl pop, sitting on a ledge, art, drunken mercenaries on the north sea, starting again, a classroom of 13 year olds, getting everything done before death, a river full of headless eels, waking up to find all music has disappeared & a choir called The17.” Learn more about the choir at www.The17.org