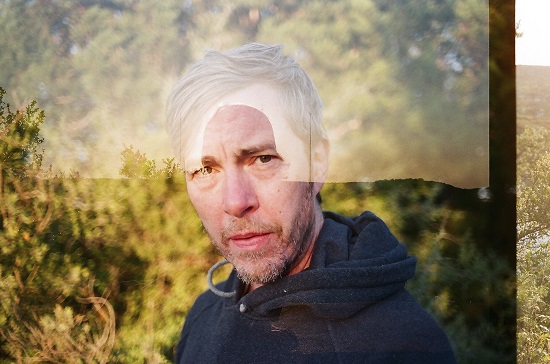

Photo by Mclean Stephenson

Since Bill Callahan last released an album, 2013’s Dream River, he got married to the filmmaker Hanly Banks. She gave birth to their first child, Bass, not long afterwards. In 2018, Callahan’s mother died, two and a half years after a cancer diagnosis. As he adjusted to this procession of life-changing events, his work rate slowed. Where before he was “a man on a desert island… a flower petal floating gently down a little river doing whatever I wanted,” an artist who would spend 12 hours a day playing guitar, after Bass was born he could barely carve out three. The result is that it has been an unprecedented wait for him to share a new record.

“I guess the long silence gave me more time to think, think about what I value,” says Callahan over the phone from his home in Austin, Texas, having just dropped Bass off at his first day of summer school. “I’ve even started to value journalists.”

Callahan announced his return via his first ever Tweet last Christmas Eve. “Alright, people! Let’s DO this!!! I am PUMPED for 2019! Woohooooo!” said the man once considered one of the most inscrutable musicians of his generation. “I’m thinking about quitting Twitter,” he Tweeted two minutes later. A few months later he trailed “an important announcement,” before revealing to his fans he’d never eaten a taco. Ten minutes after that, he mentioned off-hand that he was releasing a double album on June 14.

That record, Shepherd In A Sheepskin Vest, is supreme. At first Callahan’s voice, low, resonant and comforting, seems to ramble from image to image, from the cosmic and transcendent to the straightforward and bare. Gradually, the record reveals that these seemingly disparate images are locked irreversibly together. He finds the cosmic in the straightforward and the straightforward in the cosmic, often within the same sentence. The record is as profound a meditation on the birth, death, love and loss that he has experienced in the last six years as it is possible to comprehend. He sings on ‘Son Of The Sea’: ‘The panic room is now a nursery /and there’s renovators, renovating constantly.’

Photo by Hanly Banks Callahan

People have called the record daydream-like, but this does not even begin to do it justice. Unless you put a weak phrase like that in Callahan’s hands. “I guess you could say it’s daydreamy in the way that topics change quickly,” he offers. “Sometimes when you let your mind go you might think for a second about when you were six years old, and then all of a sudden you’re thinking about this guy you knew two years ago. The word daydream sounds very much like you’re floating on an oarless boat in a calm lake, but daydreams are kind of frantic a lot of the time.”

On a technical level Shepherd might look different to Callahan’s past records – much longer in total, but the songs are much shorter, meaning it’s more fragmented and amorphous than the slowly-unfolding, tightly wound series of albums he’s released since abandoning the Smog moniker in 2007. Yet it retains his obsession for meticulous structure. However much his writing might flicker from one small focus to another, it does so within a deeper framework. He speaks of it in the physical terms of an LP, and incidentally has been releasing it one side at a time on streaming platforms, to allow it to be digested slowly and at its own pace by a fanbase by now rabid to hear everything at once.

Photo by Hanly Banks Callahan

Callahan explains the record’s broader structure. “It starts with a kind of unconscious inner world with side one,” he says. “The last song [of side one] comes up and it’s like the dawn of now, of consciousness, about to deal with the real world, and as the album moves on it eventually leads to endings and death. It starts as a very inner world, then the record zooms out slowly, slowly, until at the end you’re out in space looking at a blue planet Earth from as far away as you can get, looking at life from the cosmic.”

He has previously described his approach to the album as ‘chronological’, broadly following a fixed progression of one event in his life to another. “I might not be able to give you the most convincing argument about the chronology of all of my albums,” he says, “but stepping stones across a river might be a better analogy. I always find a little rock poking out of each one that lets me put it in stepping stone order. I could go through the whole record and take you through how ‘on this song my son hasn’t been born yet, and then by the time it’s this song, he’s been born’. I mean even when I was recording it the engineer Brian Beattie would be like, ‘Wait, has Bass been born yet?’ He was thinking the same way.”

Lyrics reach out to one another across different songs on Shepherd – an image will appear for a minute, then sink for half an hour to re-emerge ten songs later, replying to its earlier iteration. Certain figures, charged with symbolism by the songwriter, keep on flitting into view: a shepherd and his flock, a sailor, a lion on a family crest. “I do think those archetypal, mythical images are kind of the backbone of our existence,” Callahan says. “There’s an invisible world, we are physical bodies here and we are rushing to get to work and do the little things we do every day. If life was all just surface things that are very apparent to us then we would have committed mass suicide. I think it’s important to recognise all these other stories, this other world that’s occurring from childhood. To have those interacting and recurring images, not just come up once and disappear, all of the things stay with us for our whole life. These things they keep changing. They are our parables for living.”

Photo by Hanly Banks Callahan

The record is chronological, but that is not to say it is methodical; when Callahan writes ostensibly on one theme, he allows the others to connect to it. ‘I got married to my wife, she’s lovely / And I had a son, giving birth nearly killed me’ he sings on ‘Son Of The Sea’. ‘Circles’, an elegy for his mother which takes place during the album’s latter-stage sequence of songs about death, he discusses a dying face as being ‘as stark as genesis’. The religious imagery that appears often on Shepherd, in the same role as those earlier ‘mythological’ figures, is almost always from Genesis and Revelation; Adam & Eve, the Four Horsemen, et al.

“Well those are probably the best bits of the Bible, the beginning and the end,” Callahan says. “In the last five years I’ve been in the room while my wife pushed my son out of her, and I’ve been in the room and held my mother’s hand while she died, that’s the beginning and the end too. I guess I’ve been through the extremes in the last five years and I’ve noticed the similarities of those two. Being born and dying felt very similar in lots of ways.

“When my son was being born, I wondered what it was like to be a birthing nurse or doctor when you punch the clock in the morning, then you start pulling babies out of people ‘til it’s five o’ clock, then you punch out. What is that like? I realised all the nurses had a certain blissful air about them, almost like they got high off the process. There seemed to be a golden glow in the room as the time drew nearer and nearer. I felt like I saw the gates of life that were gold, sunshine gold. I really felt our life force. Then with my mom, you know, she got a prognosis of a year and a half, and then it was about a year later that she died. It was a very slow process that I witnessed, but actually seeing death creep in over a period of months… it was awful, and also beautiful, in her last few days there was definitely a force in the room, the same gates of life. It felt very similar to the birth. She seemed like she was going where she wanted to go.”

Photo by Hanly Banks Callahan

If there is a song on the album that encapsulates Callahan’s root philosophy, it is ‘Morning Is My Godmother’; ‘She comes to me in the setting up / and in the breaking down / she shows me what is infinite / and how it fits within the grasp of man’, he sings. Explaining further, he says “I’m the type of person that every day is a new day, and every album is a new album, and every party is a new party… I think that we are given this gift as cautious humans with night and day, the sun going away and coming back, we’re given this gift of a blank slate, really. That’s what every morning feels like to me.” The image reappears on ‘Tugboats And Tumbleweeds’, a song of advice for living that appears as Shepherd’s penultimate track: ‘Morning can be godmotherly’, he sings. “I wrote that song to Bass,” Callahan says. “Brian the engineer said when we were recording it, ‘I’m not feeling it enough, maybe it would help to picture your son sitting across from you and try singing it to him’.

“But I was also trying to be a father figure to myself too,” he adds, almost as an afterthought. The musician told

Pitchfork earlier this year that “a few years ago [my father] told me, ‘I didn’t really care about any of you kids. I was just focused on myself and my career.’ It was a hard thing to hear so directly.” This must surely have been in his mind when writing ‘Tugboats’ to a younger Bill Callahan. “I think when you’re a kid it’s all you know; you just accept what you’re given because you have no choice. I didn’t have a mentor that I looked up to and listened to. I think that’s probably why I kind of led a fucked up early 20s just crashing around and trying to get the answers for myself, because no one had really told me what it was like if someone really loves you, how they treat you if they really love you. No one illustrated that for me. I find that talking to other people, they talk about the advice that their parents have given them. I feel like I had to basically make myself through trial and error.”

When his mother was reaching the end of her life, she moved at Callahan’s request to join him in Austin, Texas. He says he wanted to spend the time to get to know his real mother, a person who had always been distant during his childhood, spent between Maryland and Yorkshire owing to his parents’ employment in the National Security Agency. “I had tried every few years for the last 15 years of her life to bring our family closer together. I’d start a little campaign for a family reunion, all this stuff that naturally we just don’t do. I really wanted my mother to go to counselling but she wouldn’t go. I’d read some books so I tried to be that for her, I called her every week at the same time but she just didn’t… she couldn’t [open up]. Maybe there’s just a cultural thing where women weren’t allowed to have emotions in her generation… But yeah, I spent 50 years studying my parents and they are the least known people to me.”

Photo by Hanly Banks Callahan

Callahan had a son of his own at a relatively late age – he was 48 – and has insisted that as a result “I’m not trying to prove anything to my dad,” as he told Pitchfork. But it has enforced a fundamental change in his way of being. “Becoming a father made me feel more manly than I maybe had been, but at the same time it’s also made me feel motherly and womanly. I think being a parent you need to be a mother and father. A mother needs to be mother and father too. Also, I’m trying to figure out his brain, kids’ brains are different. Every day is a free jazz improv at deafening volume and you’re just trying to keep up! I’ve realised that it’s a crazy, psychedelic world that kids live in. My son has made up a great-grandfather and they go on all these adventures, but it seems like he’s channelling a real person, somebody from his past…”

It is indicative of Callahan’s brilliance as a writer that he ties birth, death, parenthood, childhood, love and the lack of it together into such a complete record, one that seems to find some kind of cosmic truth held by them all. The record moves in so many different ways, from birth to death, from the inner world to the outer, from the ordinary to the mystic, all ebbing and receding at different moments, in different directions. It moves on a grand, glacial scale with its overall structure and it moves deftly and subtly on a lyrical level. But the one song that ties everything together is not Callahan’s own.

In the six years between this album and his last, Callahan continued to play shows in Austin, but with none of the usual new material began to introduce covers into his set. One of them was ‘Lonesome Valley’, specifically The Carter Family’s version of the gospel folk standard, which is the only non-original to make it to Shepherd. “That song has been passed through hundreds of thousands of consciousnesses, and when you put that with a bunch of brand-new songs it becomes the glue that holds them all together” says Callahan. “I realised just recently, that song is the shepherd of the album, and the rest of the songs are the flock, the new things that are delicate and stumbling along. Lonesome Valley as the old shepherd that’s protecting them by being similar to them but much more wise. it gives it all an eternal kind of feel.”