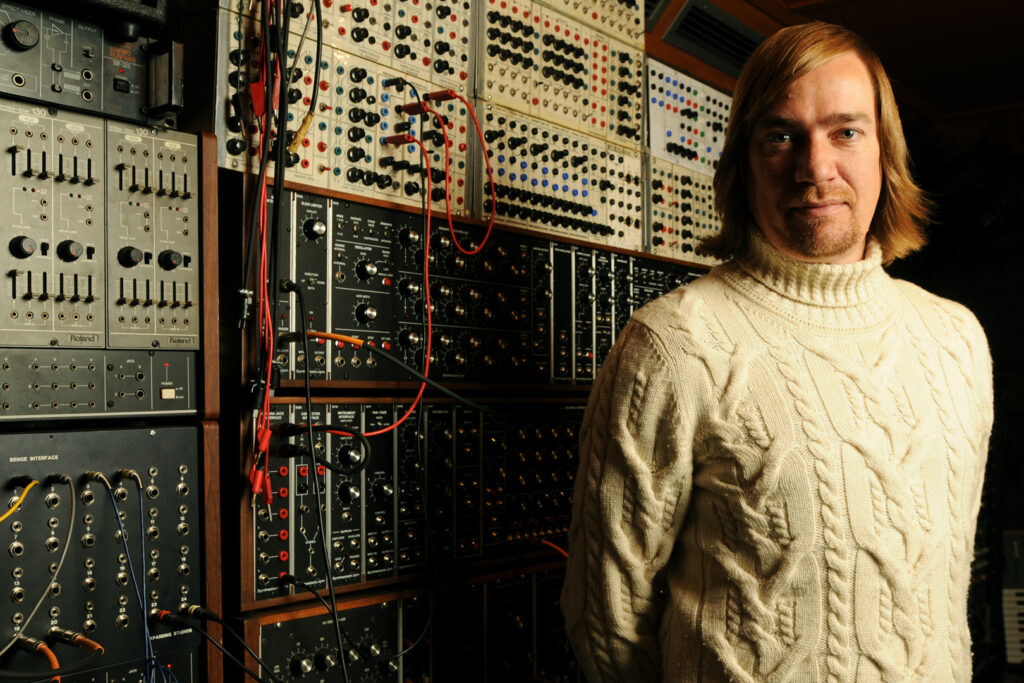

We walk down narrow stairs from the offices of Expanding Music to reach the studio that Ben Edwards shares with experimental jazz/folk outfit Tunng. In fact one of the folktronica bods is already down there doing the hoovering, listening to jazz very loud on the stereo. The cellar used to buzz with a different kind of thrum altogether though; Edwards (who looks like a much friendlier, younger, less sociopathic version of Carson Wells, the canister carrying hit man from No Country For Old Men) tells us that the cellar space used to house an upmarket vibrator and sex toy mail order firm. These days the company SH! operate out of a shop over the road and, while they don’t operate a ladies only policy, men can’t enter the premises on their own. And while it is often the case that small studios can often be tedious pits of male geekery and sites of artistically sterile equipment worship that repel all but the hardiest of female visitors, Ben’s underground den is a thing of wonder indeed. It is an Aladdin’s Cave of keyboards that makes you want to tear around pulling out and replugging in patch cables and start twiddling LFO knobs and adjusting attack, sustain and delay sliders.

Ben, better known as Benge has just released an album called Twenty Systems which traces a history of sorts through twenty years in the development of synthesizer, starting with the 1968 Moog Modular and ending up with the Kawai K5M which was released onto the market in 1987. Each song is played entirely on one keyboard with no additional effects or processing (apart from on one track but more of that in a second). It is very true that this project feels very ‘now’ with the recent years seeing re-ignition of interest in vintage synths and such figures as Delia Derbyshire and Dr Moog. Edwards started his collection nearly two decades ago however, picking up the instruments for a song when people were chucking them out to upgrade to computer software and the songs aren’t at all retro-flavoured but instead will find favour with those who like electronica and IDM. This said he must be aware of the new found allure that his collection of instruments has as the album comes with a lovely booklet portraying them all. (At the bottom of this interview, there are a selection of photographs to whet your appetite.)

What was your early material like?

Ben Edwards: "I guess I’m not from the dance side of things, I’m much more from the art music and experimental side. I went to art college to study fine arts basically. I came out really disorientated with the art world, not really knowing how to make a living out of it or anything – not that I make much of a living out of music – but I took music as my way of being expressive. I was very interested in abstract art and I wanted to make music that was like that but also beautiful to listen to."

With Twenty Systems you’ve struck a fine balance between making something that is conceptually very solid, quite experimental but also something that works in the context of it just being an album, as a record that is pleasant to listen to.

BE: "The idea to put the new album into a history didn’t come to me until about half way through making it so I already had about half of the tracks done. They were done but they weren’t necessarily to be part of a bigger project. Then when I came up with the idea it gave the album a certain sort of structure but it didn’t give it a musical structure because one track following another meant that it might not flow. It was quite random. But when I had about 80% of the album done I did start thinking about the remaining 20% in terms of what I’d need to make the album flow in terms of melodic tracks or ambient pieces."

To use an analogy, your history of synthesizers works on a genetic level not a memetic level. So the linear progression of synths happens in a specific way, oscilators improve, some parts become more complex while others become redundant. On a year by year level there is a progression in that sense on your album but you tend to ignore the memetic way that the synths were used during progressive years so that very few of the tracks sound like a song made in the year they came out in.

BE: "That is true. I didn’t really set out to do that. The synths do have a sound of their time but I didn’t set out to compose in a way that was of their time. In a way I wanted to take a snapshot of the sound of each synthesizer and just see how it would sound if I applied the same principal to each track, which was to set up a loop of sequences and let the track evolve naturally rather than impose a kind of idea on the actual composition. They are all quite similar in a way because that is the simple idea I had for each track. Some make it seem more complex than others but in principal they’re all pretty much the same."

I did think ‘1975 Polymoog’ did sound quite right for the year, a little like Italian horror movie music.

BE: "If you listen to the first track which is a really simple MOOG, it does sound like a John Carpenter horror film from that era. But that’s just because it’s what he used and it does that kind of thing really well. And again things like the Fairlight and the Synclavier – I know these instruments really well and these are the kinds of sounds I’m trying to coax out of them. The Synclavier for example still really sounds like 1986 or 1987, it has that period built into it."

There’s something very traditionalist about what you’re doing. Is this the synthesizer version of what Liam Watson at Toerag Studios is doing or is there a marked difference?

BE: "Most of my albums – and I’ve done ten up until now – have had a mixture of stuff on it. That’s in the terms of electronic instruments and acoustic instruments mixed in. This is the first album that I’ve done that has been that strict in terms of content. Obviously this record I just wanted it to be the sound of the synth with no effects or processing but normally I just chuck in every single thing I can get my hands on and then pare it down from there. This is almost working backwards to how I usually work."

In the album notes you say you only cheated on one track, which was track number two . . .

BE: "Well, it wasn’t really cheating. When I started I was going to use just one manufacturer per track so for example I’d use just MOOGs on one track but I didn’t really think that it would have the same result as in tying in the songs to a particular year. So I kind of got rid of that idea but I’d already done one song ‘1969 VCS3’, the second track and the thing that’s on it that’s not from that year is an FX unit that’s from the same company but from a later year. It wasn’t really a cheat because I wasn’t setting out to do that particular thing that early but it is the only example on the album where there is an FX on the track not from the synthesizer."

Maybe if you do it live some one will shout ‘Judas’. Talking of which, I’m guessing it would be impossible to do this live?

BE: "It would be. Some of the synths are so fragile you have to spend a week patching them just to get working properly. I’d consider doing it in London but I certainly wouldn’t take them any further and at the moment just too many of them aren’t working, like the Fairlight, it’s so fragile. I certainly wouldn’t want to move the MOOG Modular."

Can you remember what your first experience of a synthesizer was?

BE: "I’ve got quite a strong memory of that. My parents used to run a school for special needs kids and it was at home. But there was a music room and in there was a modular synth that a family friend had donated to the school. It was a box with patch cords and nobs all over it. I was probably only seven or eight when I first saw it and I remember playing on it. The room also had a piano and an organ and hand drums and things. When I was in my teens I used to mess about with these doing four track recordings. I always had analogue stuff around."

You started buying synths in the early 90s, which I’m guessing was a good time to be buying them because of the advent of cheap samplers and sequencers for the PC coming out. What was your best bargain?

BE: "People just used to give me stuff. People just used to chuck stuff out. The ARP 2600 was given to me. That’s very valuable now. The MOOG Modular is worth a lot – since he died MOOG stuff has become very collectable and I did pay a lot for that but nothing compared to what it’s worth now. I found one the MS20 in a skip. I sussed out also in the late 90s that schools and colleges would be getting rid of stuff so i’d just phone them up. They would have this amazing stuff just lying there in storage. I got a few like that."

What’s next?

BE: "I’ve been thinking about it and I’ve been thinking about doing from 1988 to the modern day. It would be a challenge because there are so many different things coming out including synths on laptops and software. There is just so much to choose from. I’d like to explore that but it wouldn’t be the same sort of album it would be a lot less retro and the years would be a lot less defined and the sound would be less defined."

Scroll down and click on the picture of Benge to cast your lustful eyes over Benge’s hot synth collection