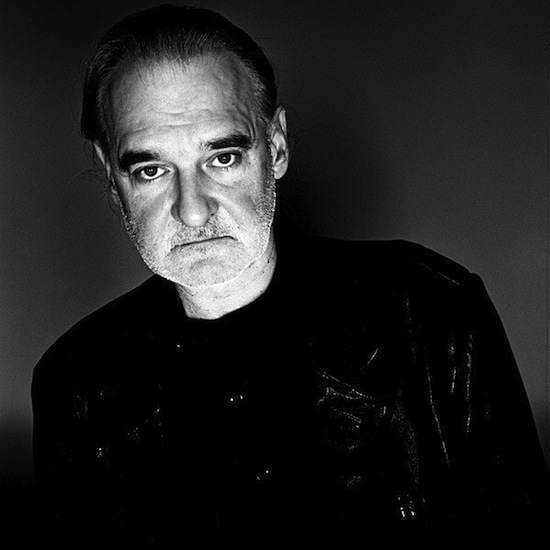

Béla Tarr portrait by Cameron Wittig

Béla Tarr’s evocative and beautiful Werckmeister Harmonies hit me hard in the winter of 2005. It was a bitterly cold, grey morning and I was standing on a train platform waiting with the other lifeless faces. The night before I had stayed up way too late and was still reeling from the effects the film had on me. "Dreamlike" is how the director Jim Jarmusch described it. I felt the opposite. I was haunted. At the time I was just starting up a new music and art project. The sound of this fledgling venture seemed to be perfectly encapsulated within Tarr’s incomparable film. Long takes filled with calming quietness that effortlessly evolved into somber sadness and then nightmarish doom. Time seems almost entirely suspended as the camera drifts from frame to frame. The words of the main character Janos (Lars Rudolph) describing/choreographing a total eclipse for the stupefied drunks in a seedy bar during the mesmerising opening scene of the film echoed in my mind: "The sky darkens, then goes all dark, the dogs howl, rabbits hunch down, the deer run in panic, run, stampede in fright. And in this awful, incomprehensible dusk, even the birds … the birds too are confused and go to roost. And then … complete silence. Everything that lives is still. Are the hills going to march off? Will heaven fall upon us?"

The train doors folded like a pair of old crow wings behind me. My fellow passengers and I were quiet as skeletons as we rumbled into the city.

Fast forward to almost a decade later. I had boldly bastardized the title of this great film and put it into service as my band name. Three albums in, my collaborators are many numbered, as are the performances across North America and Europe. During this time, sitting silently alone in a new city or staring out the window of a moving vehicle, the thought would occasionally float through my mind that if by some strange coincidence Béla Tarr were aware of what I’ve done he might not be cool with it. In September of 2014 I had had enough and decided this matter needed resolution. I wanted to talk about the film, about how it inspired and influenced my work but didn’t dare ask for any great "meaning" inherent within it. He was quoted in a contemporaneous Roger Ebert review of the film as saying, "I despise stories, as they mislead people into believing that something has happened. In fact, nothing really happens as we flee from one condition to another. All that remains is time. This is probably the only thing that’s still genuine – time itself; the years, days, hours, minutes and seconds."

Béla Tarr, 59, is looking very relaxed as he settles into a chair with a glass of lager on his veranda overlooking Sarajevo. The revered filmmaker has taken up a faculty position at the Sarajevo Film Academy and since the release of The Turin Horse in 2011 has remained largely out of sight.

"Bosnia and Herzegovina is a fucked up country and I’m working here now with almost forty young people."

You’re teaching now?

"I can’t say I’m teaching because what does this ‘teaching’ mean? It is a collaborative laboratory and this is a new way of filmmaking with new film language and I just try to push them to excel… to be free of the system and resisting outside influence. The main issue is you have to be free; you don’t have to accept any rules, or expectations or other stupid things like that. I’m working with them and it’s a very special experience."

While asking him an in depth question about Werckmeister Harmonies I notice Tarr has drifted someplace else, turning his head towards the hillside beyond the veranda.

"Sorry to interrupt but do hear this? In the minarets they are singing. Do you want to see?"

Without a pause he grabs his laptop and points it towards the hills. A stunning panoramic view of a Sarajevo hillside fills my screen and the voices of the faithful swell deep and loud.

"I am in a Muslim country now. From my place you can see fifteen minarets and now in fifteen minarets they are singing."

With little to no grace I ask Tarr if he’s aware of my work. He rakes a hand through his hair.

"I’m really fucked up. Believe me. I’m totally focusing on this shit [the film academy]. But my partner, she was listening to [your music] and she likes your stuff and convinced me that I should talk with you."

I am filled with an overwhelming sense of relief. Picking back up on the very lengthy and clumsily worded statement on how profoundly Werckmeister Harmonies impacted me Tarr quietly replies: "It is an old film."

He pauses and then very eloquently adds, "It is from The Melancholy Of Resistance, which is a really beautiful book and I love it very much. My friend Lazlo Krasznahorkai wrote this book and he asked me, ‘Do you want to make a film of it?’ And I said no. Then afterwards, about two years later, I met Lars Rudolph. He wasn’t an actor at that time he was just a street musician. He was playing a trumpet and I met him accidentally. And later on the same evening I called Lazlo and I said, ‘Now I can do this film because I saw a guy who can be Janos.’ And then it was simple. It’s not a mystery, it’s not a sophisticated thing, I just needed to see a real person in front of me. He inspired me and he moved me and then it was done."

J R Robinson portrait by Drew Reynolds

I mention the scene in Werckmeister Harmonies where Janos is gazing into the eye of an immense rotting whale carcass in the back of a truck. Janos whispers: "How mysterious is the Lord that he amuses himself with such strange creatures." This line is conflicting for me as I think of Tarr as a philosopher as well as a filmmaker. Do you believe in God?

"No. I don’t believe in God. I believe in human beings and I believe in life, the power of life, but I surely don’t believe in God. Because I do not see God. But if he exists I [have] got to say ‘FUCK!’ Because if he allows what we are doing these days he’s…"

Tarr trails off and looks out at the sunlight fading over the hills: "You have to understand one thing. I was making films for more than 34 years and I stopped. 34 years is a long time. I was doing my first movies when just one or two of my friends would be punching me and telling me how fucked up my work was. And how fucked up society was. Then, step-by-step, film-by-film, I went deeper and deeper and I tried to understand more and more. At the beginning when I was 22 I believed our problems were only social problems. But later I understood this was a totally logical problem. And somehow during the making of The Turin Horse, you can see definitely the real darkness and when you are definitely flowing into the light. And that was my goodbye to film-making and that was the point when I decided, ‘No more movies. This is the closing event.’ Without light in the darkness you cannot make movies. That’s simple."

Another remarkable sequence in Werckmeister Harmonies is a particularly dread inducing long take of a truck rumbling slowly down a nighttime street. The shadow of the trailer crawls across the walls of the city, spreading like an oozing bloodstain and pitching everything into complete blackness. Was this scene your statement on coming of age under the old Soviet system of oppression in Hungary?

"You have to understand something about Hungary. In Hungary it was always different all the time. It’s never been a kind of Soviet country because the Hungarians are too lazy. We are still [too] lazy to be real fascists even if we had some allegiance to the fascists or the communists [before]. It was always temporary. Even now, today Hungary is fucked up again like it was in the 30s. Before we were with the communists, now we have turned back to the fascist way again. But somehow the country and the spirit of the people are different. If you really want to know what was happening in the Soviet Union at the time you have to see the Soviet films. Those movies were totally different from our movies and of course our movies are more European than the Soviet films. Movies are always simply a reaction. I’m reacting for the world. And if I see something that inspires me or moves me I start to act. Sometimes I have to begin to be political, like in the last few years I have had to act in a political way too. I really have to do something because I feel my country is going to Hell now even if I know it is not going to Hell because of the people. But fact is fact and Werckmeister is a very Hungarian film and not influenced by the Soviets."

I’m particularly interested in Tarr’s view of our current state of affairs. I posit that we seem to be living in a time of weakness and doubt, of disorientation and hatred. Vladimir Putin is reviving the old-line message that fascism works best. Anti-Semitism is alive and well in Europe as well as an intense backlash against the Muslim population. Beheadings are mainstream media events. Millions starve or die excruciating deaths in Africa, bleeding from their eyes and dehydrated from diarrhoea. Americans are inert, device distracted and deeply unaffected by our perpetual state of war. Our leaders are uninterested in leading, obsessed with raising money and double checking that their golden parachutes will deploy correctly. Dark times to be sure…

"I am not living in the darkness. I’m working now with a lot of young people. And we are all really optimistic because we believe in our power. We believe our energy, and we believe our fantasy. We don’t have reason to be sad or depressed or to be waiting for the darkness because that’s what THEY want – to push you to the dark! We are not going to be pushed there. We want to be happy, we want to have energy and we are going to have it. We don’t care about the darkness even if we know it exists."

Wrekmeister Harmonies’ Then It All Came Down is out now on Thrill Jockey. Werckmeister Harmonies is available on Artificial Vision DVD