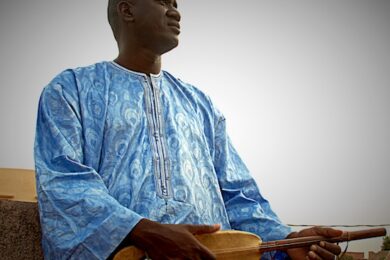

Bassekou Kouyaté’s innovation in expanding the possibilities of what can be done with the ngoni, a form of west African lute, cannot be underestimated. With his group Ngoni Ba he has developed a, literally as the name translates, “powerful” sound for the instrument, with lead, rhythm and bass roles in the style of a traditional rock band with guitars. Kouyaté comes from a lineage of ngoni players and griot musicians in his family that dates back hundreds of years.

Kouyaté has developed the music from faithful arrangements to a more contemporary sound with Ngoni Ba on the albums, Segu Blue (2006), I Speak Fula (2009), and 2013’s Jama Ko, on which he was joined by his wife and sons. Their new album, Ba Power (reviewed here), is perhaps the most striking music they have made to date, having plugged in and revved up the overdrive in a distinctly psychedelic rock style. With up to five ngonis featured on the record, the new direction seems like a natural progression.

Inspired in part by the tough recent history of Mali, this is the sound of now, as blistering effects-laden bursts of wah-wah rub shoulders with the exquisite majesty of the arrangements, as on the honeyed tones of ‘Ayé Sira Bla’. The album bridges the gap between desert rock and traditional griot music, comparable to the hypnotic rush of last year’s Tzenni record by Mauritanian singer Noura Mint Seymali and her group, who used the ardine and tidinite in a rock band setting.

In addition to his work with Ngoni Ba, Kouyaté has also worked with some of Mali’s best known musicians, including Songhoi blues guitarist Ali Farka Touré on his final album Savane and with kora master Toumani Diabaté on his collaboration with Taj Mahal, Kulanjam and the Malian/Cuban crossover record Afrocubism. And on Kouyaté’s latest LP he has collaborated with an impressive group of musicians, both from Mali and elsewhere. Among his collaborators on the new LP are avant garde composer Jon Hassell on trumpet, drummer Dave Smith of Robert Plant’s Sensational Space Shifters and guitarists Samba Touré and Chris Brokaw (Come, Codeine). It was recorded by Chris Eckman, who has worked with Tuareg rockers Tamkirest.

Bassekou answered these questions by email. Thanks to Stephane Grimm for translating.

The sound on Ba Power is a big departure from Jama Ko. What inspired the transition to this more rock style and the decision to use effects like distortion and wah-wah through the ngoni? Was it a conscious decision to move forward the possibilities of what you could do with the ngoni, sonically?

Bassekou Kouyaté: I think my sound and my quest to modernise it started right from the first album and continued on every new album I was recording. My goal is to reach more and more people with my music, because my music is African music and it carries African culture and history. I want it to be heard and appreciated by as many people as possible, so going towards a more ‘modern’ sound is a totally conscious thought.

What were you listening to that inspired the rockier sound?

BK: I did not particularly listen to specific music or bands or musicians, but from past live experience, I saw, for instance, when using the wah-wah, people were starting to smile and dance… and it also goes with my desire to have more and more people listening to my music and message; I know that young people like rock music; I hear it on the radio, and in festivals where we perform, and also like it myself! And it is fun to play, so that’s why I oriented this album a bit more on the ‘rock’ side.

Traditional griot praise songs like ‘Ayé Sira Bla (Make Way)’ and melodies as on ‘Fama Magni (The Pain of Seperation)’ are included on the new album. From the perspective of a griot, do you have any apprehension about giving this music a contemporary reworking? How did you maintain balance between the traditional styles and contemporary rock? Or is this necessary today?

BK: I think about it a lot. Basically, I have two kinds of people listening to my music: African people, who understand what I’m telling them, and that for some part listen to my music for that purpose, and the other people, who listen to my music for its vibes, and the feeling it gives them, even if they don’t understand the words. So I wanted to maintain some tradition to keep on pleasing my African audience, but I also wanted more salt and pepper, or a more contemporary sound, to please my other audience, people from Europe, Asia, America, everywhere they don’t understand the words, but get the feeling of my music. That is the balance I was and am still looking for.

‘Borongoli Ma Kununba (Borongoli Sleeps)’ refers to the name given by the griots to a mythical person with all the qualities of a king or great leader. Can you tell us a bit more about this character and what he represents?

BK: Every great personage can be called ‘borongoli’; It’s a bit like ‘your Majesty’, or ‘your Honour’, and this song is actually a song that griots would use to wake up the King; because when you are a King, you deserve to be awakened the right way; softly and gently, so using nice music was the best way to make sure the King would start his day the best way possible, and be in a good mood to go through all the duties an important personage has to.

As you have previously collaborated with the likes of Ali Farka Touré, Toumani Diabaté, Taj Mahal and musicians from all over Africa as part of the Africa Express shows, how important was it for you to include a range of guests with different musical backgrounds and playing styles on the new album?

BK: I always liked collaborations, and looking for a new sound for this album, I thought it was very important to get new musical contributions to continue moving forward. I don’t play like my father, he didn’t play like his, but he always stayed in Mali, and never had opportunities to play with occidental people, people from outside Africa. Now in the modern world, these opportunities exist and I wanted to take advantage of this new situation. That’s why I’m so happy to have gotten these guests to play on my music. I love collaboration!

Where you familiar with the work of the musicians who guest on Ba Power previously? And what did they bring with their contributions?

BK: Aside from Samba Touré, who I know very well – and I’m very proud to have him play on the album, to show collaboration between the north and south of Mali – I didn’t know the work of the other guests. We discussed, together with Chris Eckman, my producer, while recording, what were my expectations for this new album, what I was hearing. I had ideas, he had ideas, and he came up with these great musicians, and had them play on the album. And I think what they bring to my music, and the way they invested and understood it and what they brought to it is simply magnificent and magical.

I mean, the drum parts add so much to the groove we had from the start. It adds but also leaves space for the original track – brilliant! And also all the other add-ons of this wild trumpet that fits so well and adds to the harmony, and guitars, and organ… simply beautiful. I’m so happy that they gave me a part of their talent. Collaboration! I love it! And of course, Samba has his own unique and distinguishing touch, and it also fits in very well.

Jama Ko was recorded in the middle of a military coup, what was happening around that time and how were you affected?

BK: It was terrible. When I saw President Amadou Toumani Touré’s power fading and being crushed, I was devastated. He was a great and very close friend of mine. He did a lot for me and for Mali in my opinion. I was actually writing and recording a song in his honour for the album; I had to abort it. I couldn’t continue, of course, because of the political situation. It would have been dangerous and risky for me and my family. And that’s when ‘Jama Ko’ –the song – came about. This song is a praise for the unification of people, and I thought at that time it was the thing to sing, and it became the title track of my third album… No really!

It was a really difficult situation. You have to know that I had also a lot of guests during that period: my producer and engineer, and also press people, some of them were in Mali for the first time, and they were starting to get scared – who wouldn’t? And I could not show them I was scared myself. I tried to be reassuring, telling them this was political issues, that didn’t concern us, and that we were here in Bamako, in my house (I had to move the recording to my house for safety and because of power failure downtown), that everything was safe, and let’s go on with the music and it seemed to work. They started smiling again and we went through with the recording of the album, but those days were very difficult times…

How did you react to the possibility of a Mali without music as creative activities came under threat at this time and how did it impact on the recordings you were making?

BK: I was really scared – I thought it would be the end of Mali! Mali is music! Mali is known around the world for its culture, mostly music! If you cancel music in Mali, you destroy Mali! No more Mali. When you ask people around the world, ‘Do you know Bamako?’ No. ‘Do you know Mali?’ No. ‘Do you know Ali Farka Touré?’ Yes!’ Music is the heart of Mali! I was really afraid I even thought of buying a house in Burkina or Senegal, to continue to make my music and keep Malian culture alive, in case things got worse.

How is the situation in Mali now, and what were the conditions like during the making of the new album?

BK: For this album, another threat came to my family. My mother was really ill during the recording. I would come home every night, and see my mother almost unconscious. She would still ask me how it was going, and how come I was not more present. It really tortured me to leave her like that, but my brothers and sisters were there to look after her, and I would see her every night. It was torturing because I knew I would lose her sometime soon, but I had no choice. Too many things were involved. I also missed an awards show – for Songlines magazine– in England, that I was supposed to attend just before recording, but I couldn’t make it. And she unfortunately passed away about 10 days after we finished recording the album. Ba Power is dedicated to her memory, because she was a very strong woman.

There is a sense that many of the great albums coming out of Mali in recent years serve as dispatches to let the outside world know what is going on, where the story may not be widely reported. How has the situation changed your approach to music making and the message you hope to get across?

BK: The situation evolved a little, but my message has always been ‘Peace’. You know, problems in Mali are not a new thing. There were problems in the north of Mali for a long time now, way before the coup d’état. And my message has always been this one: the only solution for Mali is peace, discussion between north and south, and being united as one people, with many different cultures. There are more than 600 ethnicities in Mali and that is a strength, a positive one! It shouldn’t be a problem or a threat to strangers, visitors nor Malians themselves… Peace!

I understand you have built (or are building) a music school in Bamako, how did this come about? What are the challenges in introducing traditional instruments to young people?

BK: I’m building a school, investing around 200,000 euros, to promote the ngoni, and Malian culture at large, dance, traditional songs and repertoire, instruments craft, etc… The ngoni was almost dead after our parent’s generation. I think I can humbly say I did contribute with my modern approach to the ngoni, to bring back interest in the ngoni with the young generation, and that’s why it gave me the idea of the school. It is so important to keep traditional instruments alive, by modernising them as well.

When did you take up playing ngoni and what led you to get into playing music?

BK: I was maybe ten-or-11-years-old… My father gave me a ngoni, like it is the tradition in Mali, but I would prefer to play football… He would remind me every day to keep playing the ngoni anyway… So I would jam with ngoni by myself, when I’d get back home and, after a while, listening to what I had developed by myself, when he thought I was ready, he gave me lessons and tips and ways to improve along with traditional techniques.

How far back in your family does the griot lineage go?

BK: Since before birth of Jesus Christ! Kouyatés are the first Mandingo griots in Africa.

You have said that the instrument dates back to before the time of Christ, what can you tell us about its history and what it represents to you?

BK: The ngoni is Africa’s history! The ngoni has been played forever in larger Mali. It has been played for every king and borongoli in that country; every wedding, every prestigious visitor, every warrior! It is the witness of African history, throughout the wider Mali, in Mauritania, Senegal, everywhere in West Africa. The ngoni was the first instrument played for official and unofficial events, since the beginning of time.

With up to five ngoni players in the group featured on the record, what different role does each musician bring (lead, rhythm, bass, etc?)? And how is this reflected in the meaning of the band name, Ngoni Ba?

BK: It is like a quartet. Bass ngoni, tenor ngoni, alto ngoni, and soprano/lead ngoni. I invented the bass ngoni size, that plays in the same register as the electric bass, to support the fact that we are now amplifying the ngonis, and we need the very low register to be relevant to modern music. The three other sizes of ngonis are traditional, very old formats. Ngoni Ba, in this context – the name of my band – represents the sound that a group of ngonis produces, compared to a single ngoni. It is a bit difficult to translate in English, but the concept is that a group of ngonis is strong, and produces a powerful sound.

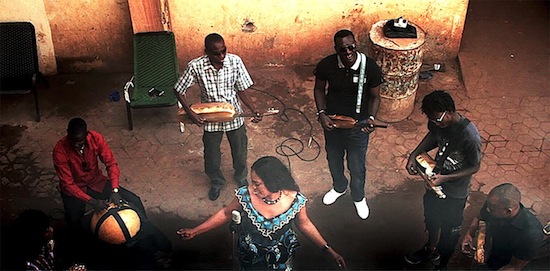

There is also a family connection, with your wife and sons in the group. How and when was the group formed? What influences do they bring to the music?

BK: This formation is the second that I had with the group. It came about for Jama Ko, the third album. Of course they help me with arrangements. The first one to hear my music and ideas is always my wife, Amy. She comments, and puts together the ideas I have for lyrics, and then the rest of the band comes in. We listen together to what I’ve recorded with my phone, and then we jam over the ideas.

Of course it is not all about the ngoni, as another major part of the Ngoni Ba sound is the singing of Amy Sacko, how important is the power her voice brings to the music? What is her musical background?

BK: Amy had her own career before we met. When I first heard her, I immediately felt her big potential, and that we could do great things together. She has a beautiful voice, very powerful and strong, "Ba," yet very sensitive and capable of extraordinary nuance. My mother used to sing with my father as a griot couple, but I’m the first one to also include in a band my sons, and brothers and nephew. It is great to tour the world with my family, otherwise, I would miss them so much.

The ngoni is now played by musicians from outside of Africa, and used in free jazz and other improvised styles. How do you view the way the instrument has been used in different settings and styles?

BK: It makes me very proud. This is my initial goal and dream. I would like the ngoni to be as popular as guitar! The guitar comes from the ngoni, and seeing other cultures emerging and playing an instrument as important as the ngoni is a very big [source of] pride for me.

The ngoni is hundreds of years old and yet on Ba Power you have shown there are still new possibilities. What are your plans for the future?

BK: Continue fighting! Continue to promote ngoni and Malian music and culture; that is my quest, and continue to evolve, along with my favorite instrument.

Bassekou Kouyaté & Ngoni Ba play at Wychwood Festival on 30th May and London Electrowerkz (please note change of venue from Scala) on 31st May. Ba Power is out now on Glitterbeat.