Graham Sutton in 2014 by Karolina Urbaniak

The Church of St John The Evangelist, a listed, grey brick building, stands on a traffic island on Stratford Broadway, little more than a mile east of where London’s Olympic Stadium was erected. Situated in a small oasis of green trees on land donated by The First Duke Of Wellington’s older brother, its steeple looms high above the grey roofs of "the piss stinking shopping centre on the new side of town" identified by Matt Johnson in The The’s 1986 hit, ‘Heartland’. An imposing, even forbidding, construction designed by architect Edward Blore – also responsible for parts of Buckingham Palace – it’s been providing inspiration and sanctuary since the mid 1830s, never more so than during the Second World War, when German bombers flew missions overhead while its crypt sheltered terrified locals by night, even as the church’s windows were being blown out.

Some four decades afterwards, and a century and a half after it was built, any alarming sounds – apart, perhaps, from the police sirens haunting this shabby corner of late 1980s East London – come from inside, from the very bowels of the building. It’s here, in a tiny, foul smelling room with whitewashed brick walls and a mouldy carpet, that Graham Sutton, John Ling, Mark Simnett and, later, Daniel Gish – the core of Bark Psychosis – gather to rehearse. Illuminated only by the dim glow of their equipment and the strip lights in the corridor beyond, they work in near darkness, at times transported from their grim surroundings by the sheer intensity and euphoria of what they’re creating. The confined space they occupy – with amplifiers in each of its four corners, and drums lining the wall – magnifies the already exaggerated dynamics of the noise they’re creating, so much that the walls seem to be moving in and out. Even outside, on the street, passers-by can make out the cacophony rising from the vaults, and these are perhaps the only times a mainstream audience will be exposed to the group. For the seven years or so that Bark Psychosis exist as something that can be considered a band, they’ll struggle to be heard. Their music’s echoes, however, will resonate for decades.

Bark Psychosis are not, even today, a name bandied about with abandon. Co-founder Graham Sutton – now better known as the producer of, amongst others, These New Puritans, Jarvis Cocker and British Sea Power – may have dusted off the identity for an album, ///Codename: Dustsucker, in 2004, and again for a limited edition, vinyl only remix of These New Puritans earlier this year, but the catalogue left behind by their original, vital incarnations is small: less than two dozen tracks. Nonetheless, these map out a brave journey of adventurous idealism that conflated minimalism and maximalism, from the incendiary noise of their disowned debut, 1988’s ‘Clawhammer’ (part of a split 7" flexidisc), via the avant garde soundscapes of 1992’s ‘Scum’ single, and on to the cultured elegance of 1994’s Hex album.

It’s probably the latter that has had the most lasting impact: those who heard it were enamoured with its radical confluence of disparate influences, its rejection of traditional structures and its complex, meticulous arrangements. But even those who didn’t hear Hex – or still haven’t heard it – will have been touched by it in some way, because it was in a review for The Wire magazine that Simon Reynolds first coined a term that has hovered over huge swathes of exploratory guitar music ever since: "The future of rock is looking more buoyant than it has for a while, thanks to Bark Psychosis and their ‘post-rock’ ilk."

Post rock is a distracting term, to be honest, when faced by Bark Psychosis, since it’s a vague expression that’s become associated with an aesthetic that, inevitably, casts a shadow backwards over what preceded it. Bark Psychosis don’t sound obviously like Mogwai, or Tortoise, or Slint, or Sigur Rós, though each of those bands could, at times, be said to reflect Bark Psychosis’ philosophy. If the band actually were post rock – those involved don’t so much dispute this as simply shrug their shoulders at the futility of arguing – it was not just because they were, as Reynolds claimed, "children of Eno, in that they use the studio to create what he’s called a ‘fictional acoustic space’, rather than simulate the experience of a live hand". Though there may be truth in that, it’s more because Bark Psychosis’ intentions were simply to put rock behind them. Everything that followed was intuitive. Intuitive and startling.

Bark Psychosis were formed in 1986 by 14-year-old Graham Sutton and his school contemporary, John Ling. They set out with the honourable intention of establishing a democratic line-up: "It was about trying to create something that was incredibly personal and ‘truthful’ to ourselves, while trying to remove as much ego out of the picture as possible," Sutton explains. "I always found the whole culture of bands, rehearsal rooms and music shops selling stupid gear – of wanting to be some sort of gang and ape the Stones – just ridiculous, and impossible for me to identify with." But, as the frontman and most vocal member of the group that subsequently developed – as well as being the only one still prominently involved with making music, something for which he has sometimes used the band’s brand – Sutton was always destined to be cast as the band’s mastermind, whether or not he (or anyone else) liked it. "It was an entirely fruitless and naïve endeavour," he acknowledges, and, as if to underline his point, Ling didn’t respond to attempts to involve him in this story.

Sutton comes from from a musical family – "My dad," he says wryly, "currently plays the organ on a circuit of crematoriums that he refers to as his gigs" – and betrayed an obsessive interest, even as a toddler, in an art form he still describes as "a mysterious force".

"One of my earliest memories was being three or four and being completely obsessed with ‘The Infernal Dance’ from Stravinsky’s The Firebird Suite," he recalls. "I would play it at massive volume, with my head on the speaker, and just feel thrilled, terrified and overwhelmed. I’d get such a rush from it. I ended up having a long phase of nightmares about it, to the point where my parents binned it!"

Before long, Sutton’s fascination led him to experimenting with tape decks, recording his own "sound dramas" and re-editing songs with the pause button. Soon, he says, he was experimenting with his turntable too. "I got into this technique of lifting the stylus just a fraction and then playing the 45 at 33. You’d get a tiny ‘blip’ of sound as the warp of the disc touched the needle, and it would create just enough traction to drag it towards the centre by an imperceptible amount, so you would very, very slowly progress through the track, ‘blip’ by ‘blip’. 12"s would take hours! I loved it, but it drove my mum up the wall."

Sutton and Ling first met in 1983, when they found themselves in the same class at a private school in Walthamstow, one that their parents would never have been able to afford had the two boys not won scholarships. "I hated it, and wanted to get away as soon as possible," Sutton states firmly, but at least it offered them useful opportunities, not least a 4 track Portastudio, which they began to employ alongside a TR606 drum machine that Sutton had picked up for a tenner. Sutton had become a disciple of John Peel’s, even calling him up during shows to berate him for playing The Wedding Present, and soon both he and Ling were ready to quit education and pursue music. By 1987, they had adopted the Bark Psychosis name, and their nascent band began performing at school. Napalm Death covers were an early staple of their set, and, as well as developing a love for the Earache Records stable, Sutton was heavily immersed in the US noise scene: he was an avid fan of Swans and much of the Blast First roster, particularly Butthole Surfers, Big Black and UT. His and Ling’s horizons stretched way further than this, however. In fact, combined, their tastes were positively precocious.

"We were also listening to stuff like Miles Davis, Nick Drake, John Martyn, The The, The Blue Nile, Eno and Budd’s The Pearl, Public Enemy, NWA, Can, Prefab Sprout’s Swoon, Happy Mondays, Talk Talk, James Brown, Parliament and Funkadelic, Lee Perry, Upsetters, Augustus Pablo, dub and sound systems, Psychic TV – obviously accompanied by long sessions of staring at inter-channel TV interference – Kraftwerk, The Sabri Brothers, Steve Reich, David Sylvian, and on and on," he lists breathlessly. "And, right as we left school, Phuture and Acid broke, and the whole scene that came with it. It felt totally natural to listen to ostensibly polarising musical worlds bumping against each other. In fact I found the contrast between them enhanced their particular transformative effect."

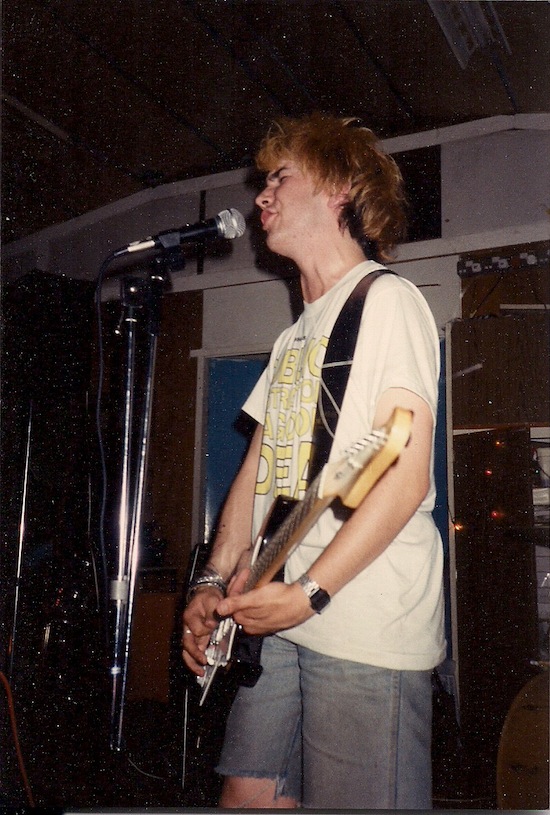

Sutton in 1988 by Vinita Joshi

In the end, Sutton didn’t have to quit school: having informed his parents in late 1988 that he intended to leave, he was caught smoking a joint three weeks before the end of his final term and expelled. He moved to a disabled care home in Edgware for the next ten months, taking time off to hitchhike around the UK following bands like Dinosaur Jr., Sonic Youth and, of course, Swans. Soon afterwards, thanks to a notice left in a music shop, he and Ling (who had dropped out of education, equally unhappy, at the same time) met Mark Simnett, a community worker and drummer ten years older than them. His presence added to the already existent, seemingly incompatible, clash of influences within the evolving outfit’s ranks: Simnett was a prog rock fan with a special fondness for Pink Floyd, while his drumming style was heavily jazz influenced. It was not an obvious match.

"They were extremely evolved as teenagers: old men in short trousers!" he smiles. "I liked their demo, although I did not think it was very revolutionary. I think it had an intensity about it which hooked me. But really it was more about ‘trying out’ with musicians who were doing something outside of my comfort zone. I remember an excellent Marillion type band wanting me to play with them at that time and I turned them down. My girlfriend thought I was crazy, and my sister thought John and Graham were too young and inexperienced to get involved with. But my instincts proved to be right."

It was Simnett who brought them to St John’s. He was running a government-sponsored project for the unemployed in the crypt, and persuaded the vicar to allow his new band to rehearse there. Sutton, who’d until now focussed on vocals and guitar, and Ling, who played bass, began adding other instruments and toying with samples. At first, the trio struggled to find a way forward, with Sutton and Ling inclined to make as much noise as they could. Eventually, however, they found what Simnett calls "a middle way", especially when working on a track called ‘Prologue’, an early version of what would later become Hex’s opening track, ‘The Loom’. "I felt the ‘oceanic, soundscape’ thing really kicked in here," Simnett elaborates, "and this resonated with the prog that I had grown up on." Sutton, however, remembers things moving faster: "Almost immediately it was palpably intense and transformative. Fucking loud, too."

Some time earlier, back when Sutton was still at school, he’d befriended fellow East London resident Nick Allport – who, with Paul May, edited a fanzine called Sowing Seeds – and Vinita Joshi, Allport’s girlfriend. These days Joshi runs Rocket Girl Records, but at the time she’d just moved down from Rugby to live with Mays and Allport in South Woodford, in what was known as ‘The Groovy Top Flat’, not far from Sutton’s parents. Sutton had first met Allport and Joshi on the platform of South Woodford tube station: they were carrying gear to a show where they would perform as a Jesus And Mary Chain tribute act called The Judas And Daisy Chain.

"I remember thinking how young he was, maybe only 15 when we met," Joshi recalls. "He came across as very bright and determined, but always broke. He’d come over and grab a slice of bread or something. He had punky hair, and was very passionate about music."

By 1989, Sowing Seeds had morphed into a small label called Cheree Records, after Allport and May’s failure to complete an issue of the ‘zine had left them with copies of a proposed cover-mounted flexidisc featuring Loop and The Telescopes. Having successfully sold it at a Loop show on New Year’s Eve, 1988, Allport and May had decided to pursue the label wholeheartedly, and encouraged Joshi to make suggestions for future releases. She was soon central to the business. When Sutton played them recordings by Bark Psychosis, it became clear that they’d work together, and before long a track was included on a split single alongside Spacemen 3 and Fury Things.

‘Clawhammer’ was recorded with Matthew Kettle, who later went on to engineer The White Stripes’ Get Behind Me Satan, as well as provide front of house sound for acts like Elliot Smith, The Flaming Lips and The Arctic Monkeys. There’s a certain charm to its scuzzy punk, but, for his part, Sutton would rather it was entirely forgotten. "God, I loathe it!" he states unequivocally. "It was a transitional thing after Mark had just joined that was recorded in literally two hours." (In a 1994 interview for a US ‘zine called Audrie’s Diary, Sutton was even blunter: "It’s crap. It’s not worth the fucking bit of plastic it’s printed on. It’s complete bollocks. Bollocks, bollocks, bollocks.")

Still, these 150 seconds of juvenilia were good enough for Cheree, who committed to a full single, releasing ‘All Different Things’ b/w ‘By Blow’ in the spring of 1990. "Graham came round with a cassette of the recording and whacked it up," Joshi remembers. "The songs hadn’t been EQ-ed or anything, and there is that quiet-to-loud bit about a minute and a half into the song. It blew my speakers!"

By this point, Sutton, Ling and Simnett had been joined by a fourth member, Su Page, on vocals, who lived in the same Leyton squat as Sutton and Ling now occupied. (They’d also tried out an additional guitarist, Rashied Garrison, but he’d failed to last.) The band told NME‘s bewitched Steve Lamacq that it had taken them six months to complete the single. He, in turn, praised this "colossal crawl of offhand feminine vocals which deliciously expand, if not erupt into cascades of sparkling guitars and ear-crushing handclaps, before slipping cunningly back into languid underdrive". Another release, ‘Nothing Feels’ / ‘I Know’, followed in October, winning them further plaudits: Melody Maker‘s Paul Lester declared it to be "essential listening", while Lime Lizard‘s Steph McNicholas described it colourfully as "like putting your hand in a pool of water and pulling out a searing slither of glass".

What all four songs had in common was their courageous, dynamic spirit, one that took advantage of, rather than overcame, the conflicting interests of each member. The singles also asserted their belief that recorded work and public performances were separate entities. Tapes of the band’s shows had always disappointed Sutton, who felt they failed to capture the intensity of what was actually happening on stage – "very under-rehearsed was the preference," Simnett declares – while studio-based, "documentary style, here’s-the-band-in-the-room-just-playing" recordings were of no interest to the youngster either. "That seemed like a lazy aesthetic cop-out," Sutton argues. "I remember reading this Kubrick quote where he was talking about natural-esque settings and he’d go, ‘Yeah, it comes across as natural. But is it interesting?’"

"Live was a lot about the visceral impact," he continues, "the contrast and power of volume levels, where there was no escape, but far less room for subtlety with our limited resources, crappy PAs and toilet ambiences. And with a record… Well, a recording can always be turned down, can’t it? You’re immediately robbed of a guaranteed part of your arsenal. So you take the approach of getting these physical and nervous system hits another way. That very naturally leads onto looking at the picture in negative, and exploring the use of silence. There’s no escape from silence, is there? But that ain’t going to work that well down the Hull Adelphi, is it? Later on, the two sides would converge a bit, but there always remained a tension about those two arenas and the different ways to maximise the intensity in each."

Ling and Sutton’s love for abrasive chaos remained a fundamental ingredient of their early releases, and an obvious willingness to break contemporary songwriting habits always lay at their heart of their work. But there was an enviable grace to the quieter moments of their singles, arguably born as much as of an ingrained love for Talk Talk’s Spirit Of Eden as Simnett’s fondness for Pink Floyd. ‘All Different Things’ was a sprawling track unafraid of moving at its own pace, its guitars chiming, its drums echoing across the room, its mood sepulchral; ‘By Blow’ shuffled ambient mutters, found sounds, Simnett’s delicate percussion and uneasy spikes of Sutton’s guitar before launching a relentless barrage of frightening, ugly chords, clattering drums and feedback. Their successors displayed a more narcotic side to the group’s nature: the terror at ‘Nothing Feels”s heart was merely implied, with Sutton’s vocals restrained and guitars that mirrored Cocteau Twins and A.R. Kane, another local band. ‘I Know’, meanwhile, was a hazy shade of autumn, its acoustic guitars circling Sutton and Page’s succinct but enigmatic, whispered exhortations – "Breathe/ I know you’ve been tired… I said to you/ ‘This time is yours’" – before the song seemed to collapse in on itself (to at least one member’s audible amusement).

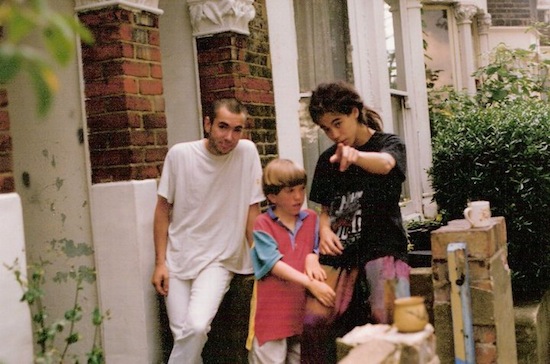

Ling and Sutton outside their East London squat, 1990

Bark Psychosis were meanwhile developing into a powerfully inventive live band. Joshi, however, recalls that the experience wasn’t always one to which they’d look forward. "They were very nervous before playing live. I remember a number of times when I’d chat to Graham before a show trying to calm him down. He was so nervous he wanted to throw up." All the same, they were earning a formidable reputation, and not just for their extreme volume and ability to provoke music journalists into rhapsodic flights of fancy: "If they send out a prayer into the unknown," wrote Melody Maker‘s Jonathan Selzer in late 1990, "they set it alight, a stormbird raging through the heavens igniting everything in its wake, a chorus of white light that holds you spellbound within its thrall". Cathedrals of sound lay just around the corner.

"The early shows were incredibly raw and emotionally draining," Sutton reminisces. "We were all very angry, frustrated and confused young kids with various hangups to vent that had found a release within the unit. That, coupled with a loathing for the culture of bands and established patterns of doing things as we saw them, meant that we felt pretty fearless about just doing whatever felt most powerful and appropriate on the spur of the moment. We truthfully didn’t give a fuck, apart from getting out of the music what we needed from it. There was always the feeling that it could fuck up at any moment because everything was so open, which of course it often did! But on the occasions it all clicked together, it was a mighty fucking force that we got lost in as much as anyone else seemed to. At its crudest, it was a sort of ‘reel them in, then bludgeon them’ strategy. Then the seduction would begin again. The whole quiet-loud thing has now become another cliché, but for a while it felt viscerally exciting to us, and was something that felt very natural. It was all tension and release, I guess, with a view towards some kind of transformative sensual experience: for us, and, hopefully, for any people that had turned up to some toilet of a pub to watch us play."

Sadly, other kinds of tension – with little prospect of release – were also building behind the scenes. In May, 1990, Allport and Joshi had started talking to two potential backers for Cheree, one being the booking agent for The Telescopes, who Allport and Joshi were managing. In addition to allowing them to work full time and to promote their product with more than their tiny budgets had so far allowed, this would, they hoped, enable them to finance studio time for the likes of Bark Psychosis, whose debut album they now wanted to release. Though this might have appeared a positive development, the band’s strong counter-cultural views were at odds with their prospective bankrollers, and a rift swiftly developed between label and artist.

"Me and John had been squatting for a couple of years in Claremont Road, Leyton," Sutton explains. "There were the usual stereotypes knocking about, but amongst them were some hugely individualistic, idiosyncratic characters that would come to have an impact on us. It was a little enclave of debauchery, hedonism and exploration. Squatting culture was a foundation and a lifeline for a bunch of bands at that time. Into this situation came these two pomaded, sport jacketed cunts as backers for Cheree. One particularly hellish winter, when we’d taken to having to rip up floor boards from a nearby wreck to feed the downstairs fire, they arrived in a gold Rolls-Royce outside the door to pick us up for some meeting. I remember that, as we pulled away, one of them turned around and offered us a peanut from the packet he’d just opened. ‘Its all we’re having for dinner, isn’t it?’ he noted, as the other nodded in agreement. It was clearly never going to work."

Despite this offer of peanuts, Bark Psychosis began to cast about for someone to record their first album, and after a chance meeting at their rehearsal studio with Lee Harris – drummer for Talk Talk – they began discussing the idea of him producing their record. While the band continued to hold at arm’s length the contract that Cheree had offered, Harris searched for a suitable studio, finally settling on a setup in London’s Elephant and Castle. Although Eliot Cohen, the other of the label’s new backers, was the owner of Red Bus Studios – favoured in the 1980s by the likes of Culture Club, Boney M and (ironically, it would soon turn out) Talk Talk – Cheree in the end offered to underwrite the necessary £6,000. This was at last enough to persuade the band to sign the label’s deal.

Unfortunately, plans immediately started to unravel. As Sutton wrote for 2012’s tribute book, Spirit Of Talk Talk, "Lee’s stories gradually got stranger and stranger. His stepbrother had been in Free, apparently. He was wanted for something or other in Australia. By the time he got to regaling us about how he’d once been in the SAS, it all became clear that ‘Lee’ was actually a basket case." In fact, ‘Lee Harris’ turned out to be a man called John Ward: "a complete hoax," as Joshi puts it, "a session drummer trying to secure production work."

On the upside, concerned by this deception, Sutton wrote a letter to the real Lee Harris that ultimately led to them meeting. They would later work together on Harris’ – and his Talk Talk colleague, Paul Webb’s – O.Rang project, and Harris also contributed to Sutton’s 1997 Boymerang album and the 2004 resurrection of Bark Psychosis. On the downside, however, the time they’d all spent preparing for recording was wasted, while the damage to the band’s relationship with Cheree was irreversible. Ward’s criticisms of, amongst other things, the label’s early desire to use Red Bus had struck a chord, and, added to the misgivings the band felt about Cheree’s new financiers, it seemed a stalemate had been reached. "Despite my very real feelings of loyalty to Vinita and Nick," Sutton says of the band’s intransigence, "we just couldn’t reconcile dealing with these pricks."

"Nothing had been properly discussed," Joshi concedes. "This caused all these complications and paranoia. The band knew that Nick and I were on their side, but we were all having difficulty with the backers. Looking back, those backers treated me terribly. I was relegated to making cups of tea and coffee while they would meet with the bands. I am only a girl, after all. I remember one time when Graham insisted on coming into the kitchen with me so they couldn’t hold the meeting until we both returned. That has always stayed with me."

The band continued to write and perform while their new management team – A.R. Kane’s company, H.Ark! – attempted to negotiate a way out of the freshly inked contract. Unfortunately, they were able to find neither a new label, nor a compromise with Cheree’s lawyers, and this enforced state of limbo took its toll. A weary H.Ark! and frustrated Bark Psychosis parted ways, Page left the group, and in fact Sutton admits that this "particularly dark period" led him to a nervous breakdown. It was only the arrival in 1991 of a new manager – Gerald Palmer, who’d previously been impressed when he’d seen the band open for Spiritualized, whom he also managed – that they were finally able to free themselves of their obligations.

Bark Psychosis signed with Corby based 3rd Stone – which Palmer co-owned – and at last returned to the studio, emerging with the three track Manman EP. The release signalled the arrival of a new recruit to the band, Daniel Gish, who’d helped form Disco Inferno a few years earlier. Gish contributed keyboards and synths, and his arrival also helped spur Sutton and Ling’s growing interest in sampling and early digital editing. Manman again reflected Bark Psychosis’ evolution: its tumultuous title track cantered through a sheet wall of guitars and sinisterly distorted vocals towards a lengthy instrumental, before exploding into a climax both beautiful and threatening. ‘Blood Rush’ – despite its title – was the comedown, and it confirmed Sutton’s desire to explore "the picture in negative", with it guitars shimmering amid the quiet of Simnett’s softly brushed cymbals as Sutton almost sighed its refrain – "Say it again/ Our world is void" – ahead of a ravishing, slow motion finale. ‘Tooled Up’, meanwhile, opened with a frantic, motorik groove – accompanied by what seemed to be an accordion, and underpinned by a simple dub bass line – before suddenly careering into the alarming sounds of a vicious crowd from which it seemed to spend the rest of the track fleeing. Confirming that their imposed hiatus had done nothing to dampen the quartet’s urge to challenge themselves, Manman‘s 19 minutes were thrillingly, dazzlingly unpredictable. They were also nothing in comparison to what they next had in mind.

With management conspiring behind the scenes to license Bark Psychosis’ as yet unrecorded debut album to a bigger label, the band retired to St John’s once again. This time, though, they took up residence in the church itself, fashioning a ‘guerrilla’ 16 track studio between the pews. Since it took them so long to write, and yet they thrived in a live setting where they had opportunities to improvise, they’d decided to take advantage of the building’s impressive acoustics and make their fourth single across a single, ten day stretch.

"I liked the idea of issuing a single track. No distractions!" Sutton says of this ambitious, risky strategy. "It seemed like a natural and exciting decision to utilise the massive space above us. I loved the sound of old Miles Davis records, and I wanted to capture the solidly 3D feeling of sound waves moving through air, creating something holographic, rather than through some processing, which always seemed to lack that true immersiveness." By starting from scratch, they hoped to capture some of the spontaneity that was the essence of their shows, and circumstances dictated that they not only work fast, but also make swift, instinctive decisions. "We only had a couple of reels of tape, so we’d just keep playing, recording ’til the reel ran out, listening and erasing before we had something we liked."

The 21 minute piece that followed – ‘Scum’, whose cover photograph of a switchblade against a blue background perfectly captured its mix of dread and delicacy – was genuinely sensational. Simnett compares it favourably (and arguably justifiably) to his beloved Pink Floyd’s ‘Echoes’ – "If you listen to that track alongside ‘Scum’, you will understand more clearly how I fit into it all" – but that’s to understate the giddy, unnerving malevolence that manifests itself: the droning feedback, the ghostly field recordings of a Pentecostal meeting, the shrill chorus of bells, the screeching saxophone. That’s not to mention Sutton’s terse, claustrophobic lyrics, written in response to the feel-good house tracks dominating the airwaves and clubs at the time: "It’s all around you/ It’s all about you/ Don’t tell me that we’re all free/ Can’t escape what you can’t see". That it was recorded in a church is unmistakeable: even if it’s not traditionally spiritual, there’s undeniably something ethereal and mystical in its expansive, resonant sound.

The mythology that’s grown up around ‘Scum’, which was released in the autumn of 1992, has been further enhanced by Sutton’s insistence that, "We just made it to challenge and please ourselves, as was everything else we did. We had no sketch, shape or anything." Simnett agrees that, "I remember ‘Scum’ developing very organically," but adds, "I think you can hold an artistic goal in your subconscious that you work towards without knowing it." Either way, little can detract from ‘Scum”s unsettling, monolithic grandeur. In fact, in its extemporaneous nature, bursts of atonal menace and long stretches of stillness – with little more than Simnett’s brushed cymbals, subtle washes of guitar and subdued prods of bass – "Scum’ was as close as they would veer into late Talk Talk territory, at least in terms of their working methods. This may well be why they ended up working with Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock engineer Phill Brown, who offered technical advice for the complicated recording process and also mixed the results.

"I think it was definitely a turning point in our mode of operation, and in other ways, too," Simnett says. "We just did it, and listening back I am very happy with what I played and improvised. I was relaxed and pretty carefree. That is a very difficult state of mind to achieve when you’re recording, so it was uniquely special in that way, I guess. One critical review said that the bass player sounded like he’d wandered off to have a piss halfway through. I had to laugh at that one, ‘cos it does sound a bit ‘lazy’. But why not? Bark Psychosis can do whatever they want. And they did!"

"Yeah," Sutton concurs. "It’s pretty solid."

‘Scum’ pushed boundaries as far as Bark Psychosis ever did. It’s the moment, arguably, where they were most post rock – in a literal fashion, as well as in the sense that Simon Reynolds later wrote in The Wire that the genre "is based not around riffs and choruses, but layers and loops (these days, executed with samplers and sequencers as opposed to tape and scissors); this ‘rock’ is always on the verge of deliquescing into pure ambience." ‘Scum’ is, one might even say, the anti-‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’, the Iron Butterfly track that many claim birthed hard rock in 1968: both were of similar length and built around extended jamming, but from there they diverged in diametrically opposed directions.

Bark Psychosis in 1992 by Phil Nicholls

If anyone was wondering where Bark Psychosis could possibly go next, fewer still would have guessed the answer: Circa Records, a subsidiary of Virgin to whom 3rd Stone – which Sutton describes as "being run out of a Northampton Portakabin as a sideline to an office cleaning company" – licensed the proposed album. "That allowed us the resources to make the record we wanted to make," he explains, "which weren’t extravagant, but were more than 3rd Stone would have been prepared to stump up for. It also allowed them to recoup their ‘losses’ and take a big old chunk as commission."

The man who did the deal was Harvey Leonard, who’d joined Virgin as a scout in 1987 and moved into full time A&R two years later. "The artists I signed were a very eclectic mix," he says now. "Circa were prepared to go out on a limb with me due to my more commercial success with World Of Twist and Definition Of Sound. By this time, Circa had become part of Virgin, and because Virgin was being fattened up for market – to be eventually sold to EMI – all A&R managers were told we could only sign one artist each that year. I chose Bark Psychosis. They were not going to be commercially successful, but musically they were outstanding."

Leonard understood Bark Psychosis’ place in the market, and believed in them to such a degree that he felt, "The only way they were going to crash and burn was because of the personalities within the band." He might not have been wrong, but neither he – nor, perhaps, any of the musicians – had yet recognised that inter-band relationships were already suffering, thanks in part to the stressful uncertainties of the previous year, and also the fact that, as egos and temperaments had over time established themselves, their goal of a democratic entity had begun to crumble.

"I had very strong ideas about where we should head," Sutton concedes, "and about how we should approach stuff, and I guess those became stronger and more bloody-minded over time. By the time of Hex, it felt like an all-consuming mission that was to the detriment of mental, physical and financial wellbeing. I can understand how the others might not have wanted to share wholeheartedly in that, but I was passionate and lost in it. If you had a very clear idea of the way something should be, and you couldn’t be persuaded otherwise, why would you acquiesce to just make someone happy?"

"It was clear from the beginning that Graham was the frontman," Leonard confirms. "Daniel was forever trying to eke out his own stamp on the band and would get frustrated if this did not hit home with Graham. John also had his views, but was not as forthright with them, and would just get moody and fester in the background, maybe because he knew Graham better than Dan did. Mark didn’t really get involved in these heated discussions, as I recall. Artistically, Graham held the blueprint of Bark Psychosis’s direction."

By the time they started recording the album in March, 1993 – having spent time writing in Cornwall at the end of the previous year – Sutton’s relationship problems extended beyond the studio. "I’d moved to Brighton in ’92 to start a new life with Kirsty Yates [of Earwig and Insides], my partner at the time," he explains. "It was just all so very, very intense. And then it fucked up royally in a pretty brutal fashion. There was fallout for all concerned. It left me seriously considering whether I wanted to remain part of all this, but ultimately my desire to finish the record and make things pulled me through. It just meant that I was even more maniacally focussed. Maybe it sparked some creative thoughts. Maybe it meant I vented more on the others, or was more difficult to be around? I don’t know: at the time it was just so fucking bleak. So that casts a pretty long shadow over that period for me to this day."

Nonetheless, there was no question everyone was eager to work and primed for the process: the experience of rehearsing, performing and recording four singles had, according to Simnett, "enabled valuable skills and experience to be gained. I think each EP was approached quite differently, with a fresh musical aspiration, gear and locations, which gave us quite a wide range of experience to draw on. There was not really a formula to work to, and we profited from that in some ways."

For Hex, therefore, the approach was again unconventional, and, Sutton says, "it took a lot of convincing and arguing with 3rd Stone for them to agree to it". The band began tracking at Moles, in Bath, before returning to St John’s to overdub and record vocals with a Fostex 1" 24 track, which they also "carted around to record piano in a friend’s front room, or Hammond at Lee Harris’ place, various stuff." Afterwards, the Fostex was taken to Sutton’s flat in Brighton, where they continued working on with further vocals and sequencing, before the record was finally finished back in London after Sutton’s breakup with Yates. The process was, Sutton acknowledges, "a little bit convoluted", but "the only way to actually get the results needed with the budget we had."

"We were quite strong on the idea of trying hard never to repeat ourselves," Sutton expands, "whether that be working methods, sonics or mood. At the time, it really felt like the music was guiding me somewhere, not the other way round, and I wanted to just be open to that and follow wherever it led, even if that was on a merry dance up the bleeding garden path. Or to the point where you’d alienate everyone around you. Just so long as it had a direct, visceral effect on my nervous system and transformed my world. I was obsessed with trying to do what I felt was best for the record and by implication – ironically enough – the band."

That irony was soon conspicuous. Sutton’s refusal to compromise meant that the band’s every penny went into the record. By the summer of 1993, unable to survive financially any longer on just income support, Daniel Gish was forced to leave. Even this didn’t cause Sutton pause for thought: he selected the lavish RAK Studios in which to mix the album.

"I knew that we needed a good, solid place after all the work that had been done," he clarifies. "After all the grief of working in these little makeshift spaces for many months, it was just wonderful. The only trouble was that going there meant we had absolutely no budget for food, or anything else. So Mark parked his camper van in the car park and we stayed in that. Food would come by the studio ringing through to tell us we could go and sneak up and eat the Fine Young Cannibals’, or whoever’s, leftovers. It was just too funny."

Others clearly didn’t find it as funny. "At the end of mixing the record," Sutton confesses, "John told me, ‘This is your record.’ He did not mean it as a compliment, more that I’d somehow betrayed those initial ideals." Once Hex was completed, furthermore, Ling quit. "Obviously I felt absolutely heartbroken and let down when John decided to leave just a week before the release tour," Sutton admits. "I think he’d just had enough of the whole machinations of music making, the whole bullshit merry go round. But more likely he’d had enough of me!"

It was, in many senses, tragic. Hex represented another surge forward for the band, and constitutes a high water mark in the development of independent music for many artists and leftfield enthusiasts. It is, put simply, a beautiful record, one that draws on a rich sonic palette to create a twilit ambience that doesn’t so much betray their earlier, rougher sound as reimagine it. More sedate than had perhaps been anticipated – though there was one more chilling burst of noise to come – it nevertheless held to their tradition of complex arrangements and powerful dynamics, while at the same time exploiting Sutton’s growing studio wizardry. Despite being the catalyst for the band’s disintegration, Hex confirms that, though they were at times mildly indebted to their influences – most notably here The Blue Nile and Talk Talk – they had carved out a niche entirely their own.

These days, it’s easy to recognise Hex‘s grace and finesse, but harder to understand why it sounded quite so revolutionary in February, 1994. That’s perhaps a symptom of the pristine production: its surfaces are so clean that they appear sterilised in contrast to the sometimes murkier depths of their catalogue to date (which can be found on a number of compilations: Independency, Game Over and Replay, though the latter two were released without the band’s involvement). Hex‘s flawless sound, however, allowed one to peer way beneath the surface, so that each of the album’s immaculately conceived elements could be clearly discerned. Since the band had put this much time and thought into their work, they wanted to make sure others could appreciate it too.

Nonetheless, without the bludgeoning qualities of their live shows and earlier singles, Hex took time to reveal its rewards. In truth, it was understated enough to slip almost entirely under the radar, and with the vulgar flag-waving of Britpop already on the horizon – something Sutton these days describes as "a fucking ‘Waterloo Sunset’ nightmare" – its champions were mainly restricted to committed members of the media and already devoted fans. "At the time of Hex‘s release," Sutton recalls sadly, "we couldn’t get arrested, and the album was largely ignored".

Hex nonetheless helped open the doors for a whole new approach to ‘rock’ music, one that acknowledged what lay behind it but looked determinedly forward. Given the fact that Sutton, Ling and Gish were all still in their very early twenties, it was an album of astounding maturity, and it owed as much to the elongated formality of classical music – such as that of Sutton’s childhood obsession, Stravinsky – as it did to the varied interests of the band’s members: four songs tipped over the eight minute mark, while the other three were at least five minutes long, allowing them to pursue a scenic route, unafraid of unexpected detours into prolonged bouts of serenity.

Like two of its inspirations, Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock, Hex paid no mind to the possibilities (or otherwise) of performing its songs live: this was indeed the sound of the studio used as an instrument in itself – the "fictional acoustic space" of which Reynolds had written – enabling grand gestures and minute details alike to add texture to the music’s substance. Sutton’s lyrics, included in the artwork for the first time, remained meanwhile elusive and impressionistic, with perhaps the most binding themes being a sense of urban disconnection and personal doubt: "I can’t relate to where I’ve been," he sings on ‘Absent Friend’, and ‘The city breaks you down" on ‘Fingerspit’. Hex also fulfilled Sutton’s dream of "polarising musical worlds bumping against each other", with its dubby, ingenious basslines, its crystalline melodies traced out by the guitars, its otherworldly sounds drifting in and out to add unexpected, harmonic minutiae as much as atmosphere, and its sprawling shapes and deliberate dissonance. Time signatures changed, key signatures changed, yet the earth stood still for its duration.

This was most true of Hex‘s closing tune, ‘Pendulum Man’ – allegedly named after Sutton’s mood swings – which ended up being used in one of Chris Morris’ most creepy ‘sketches’ for Jam. An extended, almost ten minute long, ambient mood piece destined for ultramarine skies in the small hours – much like those in the album cover’s picture of Leyton Goods Yard – it matched anything Brian Eno had ever achieved, with added guitars that shimmered just as Harold Budd’s treated piano once did. That Sutton’s next project, Boymerang, would go on to release solo material for The Leaf Label, home of the Imaginary Soundtracks compilations, says much of his cinematic sensibilities.

The rest of the album was more elaborate, with a number of guests adding instruments: The Duke Quartet (who include former Durutti Column member, and current Peter Gabriel collaborator, John Metcalfe) provided strings, most notably on the luxuriant opening to ‘The Loom’; Animals That Swim’s Del Crabtree brought his trumpet, adding particularly effective, jarring fanfares to lead single ‘A Street Scene’; Pete Beresford – the father of one of Sutton’s and Joshi’s friends, who’d played in a number of post-war swing bands – provided vibraphone on tracks like ‘Big Shot and ‘Absent Friend’, while Sutton himself added melodica to the latter. They also received programming help from a fellow former Claremont Road squatter, Neil Aldridge, who would end up working for Peter Jackson at WETA Digital in New Zealand. (Sutton likes to point out that the band had earlier played a show at Aldridge’s former private school, Oundle, where Throbbing Gristle had performed in 1980. Years later, he’d record the second Bark Psychosis album one street away from Throbbing Gristle’s Death Factory.)

In a sense, discussing Hex‘s individual songs is hard: they blur into one another, not because they’re similar but because their moods shift so (ir)regularly that each song’s twists and turns are too intricate to document. One could suggest that they exist as movements within an overall unit rather than separate entities: even if each song is more than strong enough to stand up alone, Hex is a record whose comforting melancholy is best enjoyed in a single sitting, much like those which inspired it. But to say it’s ripe for rediscovery is inaccurate: in a sense, it’s never gone away. It’s simply bided its time, keeping a low profile, allowing people to find it at the same, composed pace at which the record gestated and, indeed, operates.

That Hex all but disappeared upon its release wasn’t only down to its prescience. With Ling and Gish out of the picture even before it reached stores, live promotion was an immediate problem: only five shows, with a hurriedly assembled line-up, took place shortly before Hex‘s release. (These were distinguished by the odd fact that Gish rejoined the line-up as a session player, and support came from an hour-long, stop-motion animated film, The Secret Adventures Of Tom Thumb.) A further tour would follow in late spring to coincide with the release of a new single, but, bewilderingly, this wasn’t taken from the album. Even though it included a track called ‘Hex’ – a deafening burst of white noise recorded at St John’s that slowly receded to become something far more tranquil – its lead track, ‘Blue’, confirmed that Sutton’s interests had now strayed far from the path on which Bark Psychosis had first set out. Perhaps it was symptomatic of the loss of his two colleagues, but this sounded like futuristic electronic pop, with a Peter Hook style bassline butting in towards the end to provoke comparisons with a nightmarish New Order.

For Simnett, the Blue EP – which also featured an ‘Alice S Cheshire Cat Mix’ of ‘Big Shot’ by A.R. Kane’s Rudy Timbala – proved to be "a bend that was too sharp for me for to corner", and he announced that he, too, had had enough. "The state of the band and the music at that time did not tick any boxes for me, so it was an easy decision to make. I do like Blue, but know that I was not functioning right, and consequently gained no satisfaction from it. I actually got the impression that Graham would have preferred it if I had stayed to support Bark Psychosis, which surprised me. But I was so glad to get out. I felt exhausted by it all."

"Things fizzled out because of what was happening within the band," Leonard adds. "Frankly, they were exhausted after the fractious recording sessions. This was not a commercial singles band that could tirelessly promote the record through numerous channels. Media beyond press was limited – this was pre-XFM, pre-Later with Jools Holland – and touring at the time was very expensive, even putting aside what the band wanted to do with the live show with quirky venues and films rather than support bands. In fairness, I was frustrated with the band at this point as we had done pretty much everything asked of us, but there was no easy way forward."

It was, to all intents and purposes, the end of the road for Bark Psychosis, at least for the next decade. Although the band appeared at Britain’s Phoenix Festival that summer, they were – despite the presence of Sutton and, once again, Gish – almost entirely unrecognisable. The two of them had been swept up in a rush of drum and bass, and, by January, 1995 would release their first 12" under the name Boymerang. (Gish would again leave Sutton’s side shortly afterwards, and just one Boymerang album, Balance Of The Force, would be released, by Regal Records, in 1997. Talk Talk’s Lee Harris contributed drums.)

"I just didn’t give a shit what anybody thought," Sutton explains of that dramatic step sideways. "I just wanted to be involved and contribute my part to a music that seemed vital and had changed my life again. Sundays at The Blue Note were just legendary. The experience of writing a track to please yourself, giving a DAT to someone on the Friday to cut a plate, and then see the whole place absolutely lose their shit to it when it dropped on the Sunday, knowing full well that they’d never heard it before and have no baggage attached to whom or what it may be, was beyond incredible. Real life-affirming stuff."

In the years since, Gish and Ling have both, according to Sutton, "dropped off the radar". Simnett, meanwhile, went on to work a while with Porcupine Tree’s Steven Wilson, as well as Yellow6, and these days he’s a father of two who teaches maths for Derby Adult Learning Service, and also gardens for The National Trust. As for Sutton, he moved into production, but quietly released a second, low key but rewarding Bark Psychosis album, ///Codename: Dustsucker, in 2004. Despite the decade that separated it from Hex, it picked up from where its predecessor had left off, the continuity emphasised by its use of ‘found trumpet’ and ‘found drums’, recorded by Del Crabtree and Mark Simnett respectively years earlier. (It, too, included new drum tracks laid down by Lee Harris). The fruit of four years’ work, its musical proximity to Hex confirmed Sutton as the driving force behind that first record: much of its hidden tension remained latent in these new, jazzy, similarly protracted pieces, their depths disturbed by perplexing noises, their arrangements as unconventional as the band had always been. Sutton, incidentally, hasn’t ruled out further activity in the future, though he’s clearly in no rush.

"I’m just not interested in clogging up the place, I suppose," he reveals. "I’ve always wanted to make something that has real meaning or significance to me, and not for any other reason. The wheels will turn again at some point, but only when I say the time is right. It has to be at the point where I have no other option."

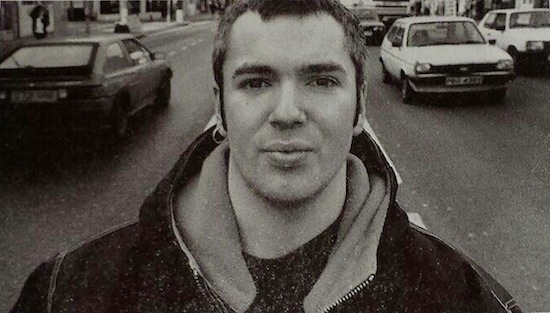

Sutton in 1997 by Phil Nicholls

Back on Stratford Broadway, almost two centuries after it was built, The Church Of St John The Evangelist still dominates the skyline, even though the area has changed dramatically: billions of pounds have been invested in the district since it was announced that London had won the Olympic Games back in 2005, and it’s now considered one of the more desirable parts of the capital in which to settle. Hex, in the meantime, has come to stand as a testament to the extraordinary artistic pilgrimage undertaken a quarter of a century ago by a small group of earnest, local musicians. Like St John’s, it too continues to offer inspiration and sanctuary, but unlike the church’s, its congregation keeps growing. For Sutton, this is the ultimate vindication of Bark Psychosis’ lengthy, tortuous adventure.

"I’m pretty uncomfortable with looking backwards in general," he concludes, "and that chapter is so painful in many ways that, regardless of how I might feel about the record, I don’t like dwelling on it too much. I hate the whole heritage, box set mentality. I know what that music genuinely meant to me, and as far as I’m concerned that’s the end of it. I’m answering these questions now so hopefully I won’t have to again. But we made the album I dreamt of. It was met with a collective shrug and a quizzical look, and I just assumed that that was the end of life of the record. But it’s something that’s gradually snowballed throughout the years, largely through word of mouth, it seems. It’s enormously gratifying…"

Thank you to Vinita Joshi, Harvey Leonard, Mark Simnett, Chris Stone and, of course, Graham Sutton