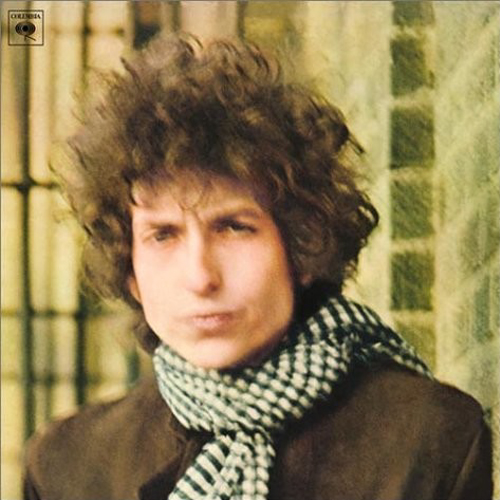

4. Bob DylanBlonde On Blonde

I never really like Bob Dylan The Folk Singer. I realised that university students thought he was saying amazing things and ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’ was an iconic song but I didn’t like that period of Bob Dylan. But when he got that electric band going I was not one of the ones who said "Judas!" I was one of the ones going "it’s about fucking time!" He was great! It’s been proven down the decades that he’s pretty much a great rock and roller too. And a very evocative voice.

What I loved about Blonde On Blonde was that it was definitely seat-of-your-pants recording. He didn’t like to rehearse and he didn’t like to do more than one or two takes. And he was very smart, or his producer was very smart, because [he had] top session men who could just read the chord sheet or just remember a five-minute talk-through and then play it like they knew it all their lives.

Having said that, if you listen to Blonde On Blonde closely, there are hundreds of mistakes. If it was recorded nowadays and they used Pro Tools and fixed all that then it would sound like a crap album. Those mistakes are so charming and I love it that an artist has the courage to keep all those quirky things in, because that’s just 1000% personality. If you start removing those things and you start fixing them then you’re making the record more and more bland. Who are you doing it for? The fans certainly love all those little effects and they love every little squeak and messy thing; they love it! That’s just as important as the lyrics and the music. That’s what Blonde On Blonde taught me.

At the time, I had a wife who was a complete Dylan nut. She was a very articulate and very wordy person and I couldn’t understand half of the metaphors on the songs and she spelled it all out to me: "here’s what these songs mean." And I loved her for that. And after that I really started listening to Bob Dylan The Poet. He really stood up for me and he did a far more minimal album after that. If you’d have given me 14 albums to choose, I’d have also added John Wesley Harding which was bass, drums and Dylan playing an acoustic, nylon string guitar with a plectrum and he tooted harmonica every now and then. But the lyrics on that! Oh! Hendrix took about three songs off that album and made them his own. But what a great batch of songs and what a great batch of lyrics came off of that album too, and I think Blonde On Blonde was encouraging and the beginning of the Bob Dylan that I eventually learned to love.

What I learned from Blonde On Blonde and similar albums I carried over into the T. Rex days and all my David Bowie albums. Because I remember Marc hated to do too many takes on one song. If we went over five or six takes he felt that the song was too clever and that it didn’t belong on the album or that it was overdone. The band would say "oh, I’m just learning the song" and Marc would say "no, it’s got the vibe!" I would take Marc aside and I would say to him "you’re absolutely right – it’s got the vibe which is more important than getting every note perfect." A lot of T-Rex fans love the fact that those albums sound very live, like everyone was having a load of fun in the studio. There were a lot of emotions. Marc was having tons of fun jumping up and down and playing like he was onstage, but there was loads of anxiety and tension that was beneficial to that sound.

I’ve often discussed this with David Bowie and he loved that sound too. He never overdoes anything. Back in the day he would get good musicians and I worked with him we would wait for mistakes to happen. We would say, ‘That’s wonderful! That’s perfect!’ and we’d keep it in unless it was an obvious and terrible mistake like the wrong two chord changes then we’d do another take.

But that’s what I got from Blonde On Blonde and I certainly used that on my Bowie and T. Rex albums. Maybe that’s what Eno took from it [with his Oblique Strategies]. Mistakes are the most precious things in art. You can’t tell me that a painter’s every stroke is perfect. If it was perfect then you’d be a graphic artist. I work with artists who have great swagger and Eno’s got great swagger too. He lives for his accidents as well. You have to practice and you have to know your instrument but in the studio you have to get into the frame of mind that you’re going to lay something down that’s eternal and you have to be prepared to accept your mistakes. It reveals something inside of you that haven’t planned and something spontaneous and something very, very Zen. A lot of people of my generation – back in the day – we were really into that aspect of making records.