8.

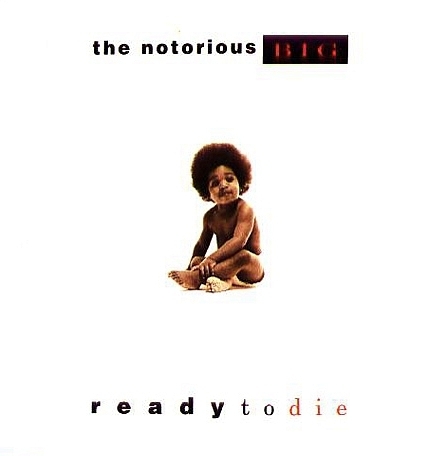

Notorious B.I.G – Ready To Die

Brilliant, brilliant. I know ‘One More Chance (Remix)’ ain’t on there – his original’s on there – but Biggie’s one of my favourite rappers. Everyone’s probably either Team Tupac or Team Biggie [but] I didn’t really get into Tupac until the last 10 years, I was just proper Biggie, his storytelling was out of this world.

After Public Enemy – I wasn’t really into Wu Tang until late, until 95, 96, so I didn’t really get into the Wu Tang epidemic – [it was] Notorious BIG. He made the hardcore tunes, he made the soft tunes, the commerical tunes that no other rapper could spit on, he made it cool. When jungle was the fashion in ’95 and I was just at school, except for jungle, [if] you put on hip hop or R&B you could not go more than two seconds without hearing a Notorious BIG record. If you didn’t play a Notorious BIG record, and the girls weren’t singing along, you’re lame, don’t DJ!

Biggie’s raps, and his whole dress sense, was a jungle dress sense! He made it hip-hop! The Versace glasses, we was wearing them in jungle raves, so when he was saying "Versace glasses clocking you", everyone knew the lines. He’s as quoteable as bar none. You see girls singing along and you just sing along to his catchphrases, he was just that guy. So yeah, Notorious BIG, that’s one of the moments for me growing up, that was a part of my life, that was my raving experience.

You talk about the importance of storytelling in hip-hop, and while grime evolved primarily from the UK dance continuum, were people like Biggie major influences on that first wave of grime MCs?

Yeah, course! When the grime scene first come about, everyone was into Jay Z at the time, and you had Ludacris and everything like that. I know Dizzee, a lot of his influence was the dirty south rappers, Ludacris and those guys. But I think that a lot of the time, a lot of the MCs were taking a lot of lyrics and using them as their own [laughs]. Because MCs originally were just toasts, [but] jungle was where it all started really, people spitting 16 bars, people like Skibadee, Shabba, they were were turning the toast into artistry. But when garage came it kind of went back a peg, because it was like ‘we don’t really want that, we want the music to do the talking’. So when grime came about, that’s when it got lyrical again.

It’s interesting isn’t it – talk about the evolution of UK dance styles so often focuses solely on the music, but actually the MC has evolved along with them too.

I watched the whole thing evolve. I feel old. Now I’m only 33, but I was sneaking out of the house when I was 13, 14… I’ve been raving since I was 12, even, so I’ve been doing this 21 years, almost 22 years. Flippin’ hell. I’ve watched scenes come and go, I’ve watched genres come and go, and I’ve watched how things evolve. I’ve watched how certain MCs spit, and I’m going, ‘ahh, you took that from here, you took that from there’. Clever MCs take it and make it their own, and patent it themselves.

I watched Dizzee Rascal come up and it was like, ‘woah, this guy’s different, man’. A lot of people didn’t really take to him, it was weird. I love Dizzee, when he made ‘Go’ and ‘Hoe’ and that – and especially ‘Wheel’, I was listening to that tune on repeat, just a loop – he changed the game with that.

The whole MC thing was like, you can tell the influence was a lot from dancehall and hip-hop – where else were you going to get the influence from? – and then hip-hop’s influences come from dancehall anyway. All the early jungle stuff was played on [reggae] sound systems by Saxon and Coxon, and they all played one or two jungle tunes. MC Navigator was one of the biggest MCs on Kool FM at the time, and he used to go out with someone on my road back in the day – we used to call him Speccy Ranks – and he was a part of a big sound system called Unity Sound. The Ragga Twins come from Unity Sound, and a few other people.

So it all comes from the sound system culture, and I think our sound system culture has only been highlighted a little bit with the whole dub side of dubstep – a little bit – but our history of sound systems over here is actually the backbone, and it’s never really highlighted, which is a shame. It’s almost kept in the dark. It’s almost that everyone’s trying to lean towards the Ministry Of Sound or the Fabric situation, and it wasn’t just that – if it wasn’t for the soundsystems you wouldn’t even have these club events. It was church halls, all kinds of places where you could get the music when you couldn’t get into clubs, like private functions. That’s how the music lived.

Places you’d feel it physically.

Yeah! They wouldn’t allow the soundsystem culture, that’s why back in the day you had house parties and house raves. Nowadays the clubs are more lenient, they allow you to go into the clubs and put on the events, but back in the day it was almost unheard of to put on events in clubs unless you owned the club. And the licensing was relaxed, but it was still hard to get a license, so you’d probably just hear of someone hiring out a church hall or a function hall and then putting on dances in those places.

When I was growing up that’s where we used to go to – church halls, youth centres – which used to go on ’til late, it’s not like they’d finish at 11, they’d finish at 6 in the morning! It would still be over 18 events, so it wasn’t like it was a youth event – it was a proper rave in a youth centre. It’s only when you saw the change from 93 to 95, where all of a sudden the clubs relaxed their license and health & safety and noise patrol said, ‘if you play music at a certain level, we’ll arrest you’. That’s when it all changed. Before that, you could have a house rave and they couldn’t say a thing – call the police, the police say "turn it down". [You’d say] "No." Now even if you own your house you get a fine – and even worse, if you don’t own it, you get evicted. That [whole development came] from raving culture, which changed it all. But that’s another story!

Well, the next one is Soul II Soul, which is obviously very much still linked into UK soundsystem culture…

Exactly, exactly…