10. Johannes Brahms

Schumann declared the young Brahms to be the future. Brahms’s own contemporaries, in later years, thought of him as conservative in comparison to Wagner. Brahms: even the name sounds dour. The stodgy-looking heavily-bearded man who looks back at us from his portraits doesn’t do much to counteract the impression of a starchy ‘greatness’. Schoenberg did his best to convince us of Brahms’s harmonic and rhythmic radicalism, but the taint has remained. He is central to the tradition, and sort of ghettoised in it.

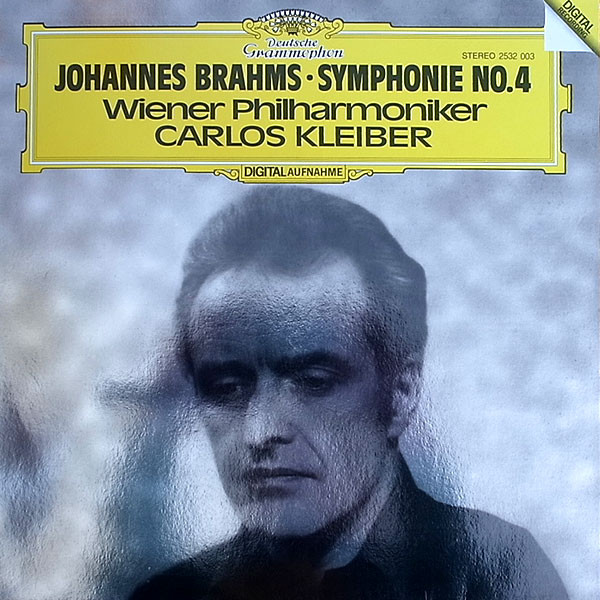

They said that Carlos Kleiber only used to conduct when his freezer was empty. He didn’t care for the whole dog and pony show of the great conductors’ circuit. He was minimalist, ferociously precise and full of humane virtue; a magician on the podium, a handsome man with a dance-like style. Another legend has it that he gave a concert once on the condition that he be paid with a brand new Audi A8. He conducted, got his car, and drove away. Carlos Kleiber never gave an interview. He was especially good in Brahms, using that gift for precision to draw out the great heart of this composer. He studied every score in manuscript, listened to all available recordings: the slow movements are like young rivers, clear as glass, and the fast movements are ballistic missiles.

Kleiber’s Brahms’s 4th, recorded in 1981, is my desert island disc, and not only mine.