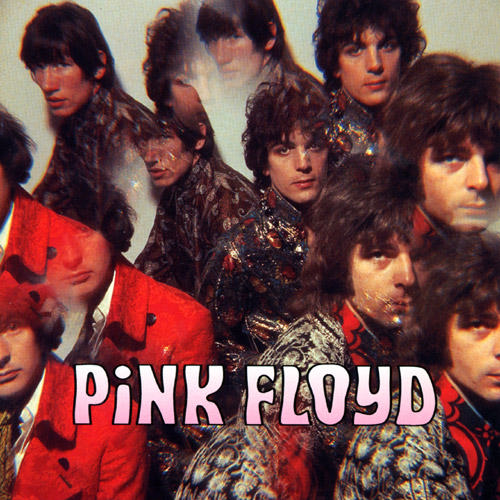

6. Pink FloydPiper At The Gates Of Dawn

Pink Floyd were, initially, a pop group. Even though they were presented to the world as a pop group, they hadn’t really started as one. They started, really, as an experimental sonic collective that appealed to people like [future Pink Floyd manager] Peter Jenner and [producer] Joe Boyd who were jazz fans. They weren’t pop people, especially Jenner. They’d obviously listened to The Beatles and Dylan and Bo Diddley and the largest part of ‘they’ was Syd Barrett.

They seemed to be going on two opposite directions at once and arguably this is part of what tore Barrett apart. I don’t think that would have happened without the drugs but the side that the record business presented to the public was melodic pop. ‘Arnold Layne’ and ‘See Emily Play’ were almost like children’s songs; his words were very childlike, in a way. But they were also dark and creepy and not like Donovan or The Incredible String Band. They weren’t fey; they were both whimsical and creepy which is why their appeal has lasted for so long. They appeal to songwriters and critics alike which is why generations keep on discovering this stuff.

I remember talking to a man who was in an early line-up of The Thompson Twins and he told me that when he was nine or something his parents had bought him a copy of Piper At The Gates Of Dawn and that he cried because it had ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ which he didn’t like because he thought it was a bloody racket and this chimes with those stories of those people who were out in the sticks throwing coins and pouring beer over them. I remember meeting a 17-year-old girl – I was only 14 and so I was staring up her nostrils and looking in wonder at this great creature who towered over me – and she said she seen Pink Floyd play in a barn in Gloucester and she didn’t understand it. She thought it was a noise.

Even at the time I think they were aware of the dichotomy at the heart of them. There was the experimental side and that thing that Barrett had of not wanting to repeat himself. I think there was some quote from his sister after he died where she said he never did anything twice. That’s the dream of any creator – that anything you do is new. But every snail leaves its trail and every spider weaves its web and it’s hard to get away from patterns, even if you’re John Coltrane or Miles Davis or Captain Beefheart. You’re going to have recurring motifs but everything that Barrett did was extremely original and as I’ve said many times, I think his talent was condensed. Most of us eke out a tube over a lifetime and he squeezed the whole thing out in about two years. Maybe if he’d been more able to make decisions and not been left shattered by the whole thing then maybe he could’ve become a more effective painter. Who knows? It’s all part of the mystique that he intentionally or not cultivated.

Emotionally, this is in quite a narrow plane. You put The Beatles on and all human life is there – it’s warm and you feel a warm humanist glow coming out of you – but when you listen to Barrett’s Floyd your temples throb in the way your mind does and you can feel the mania in this that eventually became psychosis. It was becoming psychosis as it was recorded and it’s not surprising Barrett had a massive breakdown from which he never recovered. But at least he had something to show for it.