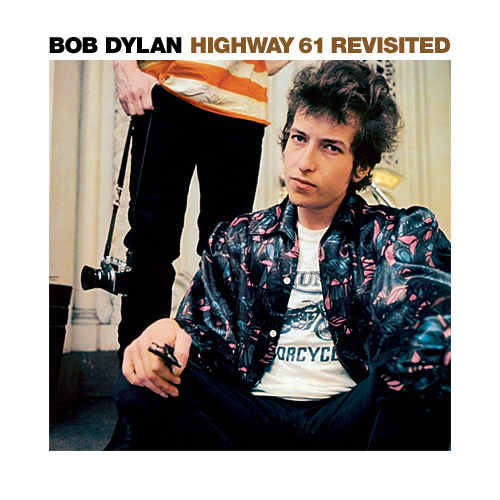

2. Bob DylanHighway 61 Revisited

I remember when [The Byrds’] ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ came out and my cousin, who was nine years older and was one of my gurus, said, “Some pop group’s done ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ and I don’t know about that!” Because to him folk and jazz where the cool things. He liked Dylan and he like John Coltrane but he wasn’t necessarily going to go for The Beatles or The Byrds because he thought it was a little bit vulgar, that stuff.

And that all changed with Highway 61 because Dylan had got hold of The Beatles and they’d got hold of him. Now you realise that The Byrds were simply The Beatles and Dylan mating and they were their offspring, but I heard them before I’d heard Dylan so I’d worked my way upstream to Dylan. Then, I just hadn’t heard anything like it. It sounded like this voice was speaking directly to me. This voice was like coming out of a cloud and saying, “Listen here, Robyn Hitchcock, you will go forth and play the guitar for the rest of your days! This is what you are going to do!”

He didn’t know he was sending us all off to do this but loads of us did and like tadpoles some of us turned into frogs! Others just got eaten by herons and got straight jobs, man!

But there it was and now, 46 or so years later there’s still nothing like it. It was kind of music that had never happened before because he brought Brecht and poetry and a whole load of things from one medium to another like Bowie brought theatre into rock. But with Highway 61 he brought in Mike Bloomfield and The Butterfield Blues Band and he brought in Bo Diddley, essentially. It was kind of the template for what he does now but funnily enough, what he does now is more old-fashioned than Highway 61; he plays kind of jump swing these days and I think he kind of sees himself as a cross between Howling Wolf and Jimmie Rodgers.

But back then there had been nothing sonically like Highway 61 or like ‘Tombstone Blues’. What The Rolling Stones and The Beatles were doing, he’d obviously listened to it but his stuff was much more intense and, up to his bike crash, Dylan had the energy to make everything intense. Listen to Blonde On Blonde [adopts Dylan voice]: "Every. Word. Is. Em-pha-sised!" There’s not even a gap to put a punch line in. His timing is still great to this day but it was like Syd Barrett; it was undiluted talent and doubtless fuelled by the times and the dope. He was on the right side of his drugs at that point and everything was just enhanced and clarified and he was only 23 or 24. I didn’t write a decent song till I was 25 and by that age Dylan had peaked.

He did well. He was grounded in Minnesota iron ore so he’s always had a foot in reality but when you have that many people staring at you it’s hard to be an observer and Dylan was great when he was an observer. He was still an observer when he wrote Highway 61 and he wasn’t reacting to people reacting to him. You could feel him getting angry, that as he grew more successful he grew angrier at what was happening to him and perhaps that made him angry with himself. Maybe it was the toxicity of the drugs or the people that were surrounding him or contempt perhaps that he felt for the public and the fact that it took a while for people to catch up with him.

It led to him, by the 70s, being very self-involved and sounding rather petulant. You listen to ‘Idiot Wind’ and there’s a lot of anger in there but it’s like some animal that’s been woken up: “Oh fuck! What’s all this! Oh God! Go away!” It sounds a bit graceless but Highway 61 is really angry but it’s also really exuberant and he’s pointing his fingers and complaining about Uncle Bill and railing against the princess on the steeple and Mr Jones, I think, is Dylan. I don’t think you can have it in for somebody like that unless it was for yourself. To me, it’s the idea of being very paranoid and you’re stoned. There’s a great line in Dylan’s novel, Tarantula, where he says: “Zonk hated himself and when he got too high he thought that he was a mirror” and I think ‘Ballad Of A Thin Man’ is like somebody’s got stoned and is having this terrible existential horror – “Oh my God! I exist! Aaaargh!” and then all these lines from Scott Fitzgerald start appearing. I read The Great Gatsby again recently and found all these lines in Love And Theft.

He’s angry but he’s exuberant. That’s what I love about Dylan. At his best, he’s such a mixture of contradicting emotions. You’re not just getting rage, you’re not just getting humour, it’s all mixed in and that’s why that stuff lasts.