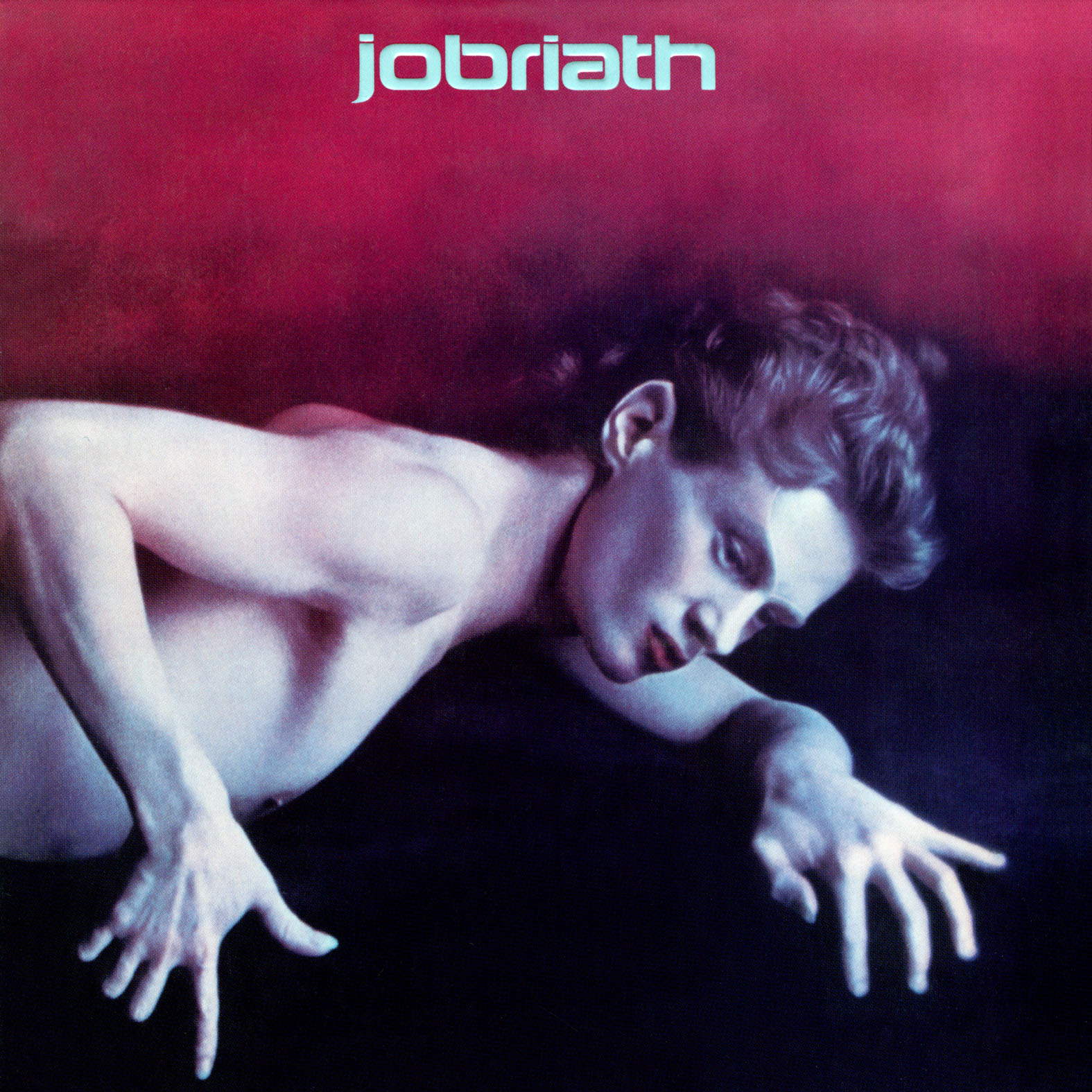

1. JobriathJobriath

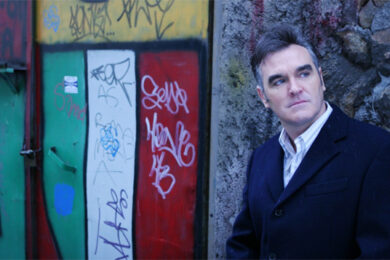

Not least due to Morrissey’s efforts – most notably overseeing the release of the compilation Lonely Planet Boy in 2004 – Jobriath has been slowly emerging from a terribly undeserved obscurity over the last decade. Back in 1973, pretty much every music fan was briefly aware of him due to manager and boyfriend Jerry Brandt’s arrogantly audacious publicity campaign, which included putting a 40 foot high nude picture of the singer on billboards in Times Square before the public had even heard a single note.

None of this went over at all well in the authenticity-obsessed Old Grey Whistle Test era, but when Jobriath himself batted away accusations that he was simply copying David Bowie’s sexually ambiguous is-he isn’t-he Ziggy persona with the claim to be "rock’s true fairy", he pretty much sealed his fate. Quite simply, he was far too gay, and far too open about it, for the mid-70s rock press. The NME‘s snide and overtly homophobic dismissal of his remarkable debut album as "the fag end of glam rock" was typical of the responses he received at the time, getting booed off stage for being gay even in New York. After releasing a second album less then six months later to widespread indifference, Jobriath was abandoned by Brandt and his record label Elektra, and disappeared, eventually dying at the age of 37 from AIDS-related illness in 1983.

This would be a sad tale even if he was the hyped vacuity he was perceived to be, but listening back to this wildly ambitious debut renders it positively heartbreaking. Yes, Bowie is a clear influence, but then, Bowie himself is pop’s most notorious magpie, and the striking similarity in the cover design of Bowie’s Diamond Dogs LP a year later suggests this wasn’t a one-way street. But in any case, there is a lot more going on here, from the forward-looking disco-rock of ‘World Without End’, to the in-your-face gay anthem ‘I’maman’, to the agonisingly beautiful solo piano and voice ‘Inside’.

Furthermore, it’s in the ballads rather than the obviously glam-era stuff that you can most clearly hear his influence on Morrissey, with songs like ‘Be Still’ and ‘Blow Away’ being clear ancestors of his piano-led elegies of recent years.

The follow-up album, Creatures of the Street is arguably even better, and, astonishingly, was culled from the same sessions that produced the debut. Neither album contains a single scrap of filler, and while Jobriath’s own drug and mental health problems no doubt contributed to the derailment of his career, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that widespread prejudice robbed the world of a major talent. John Tatlock