2. Glenn BrancaThe Ascension

I was playing in this early band that I had called The Flucts and even before we moved down to New York we’d come down on weekends to see some stuff and started to get inklings of what was going on at CBGB’s and Max’s. We’d see early shows by Patti Smith and Television and Richard Hell and Teenage Jesus & The Jerks and The Contortions and all that stuff.

One of the first things we saw when we were coming down, we went to this weird gig at Max’s and it was the week after there was this really intense nuclear meltdown in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Three Mile Island was the place and it was a really huge early nuclear scare and everybody was freaking out. The next week we were looking for something to do in New York and Max’s had this bill that said “Friday Night – Meltdown” and we laughed our heads off and thought this has got to be good, what can this be about?

And it wasn’t Glenn Branca’s show, it was a show by Rhys Chatham but they were kind of like mortal enemies and kissing cousins, the Phil Glass and Steve Reich of the Electric Guitar set. Rhys was putting on that famous piece of his ‘Guitar Trio’ and it was an intense night. The place was filled and they came out – there was Rhys on guitar standing in the centre with this leather vest on over a white shirt and these Roger McGuinn granny glasses. He looked really weird, he had poufy hair and stuff. He had these other two guitar players in the background and one of them was Glenn Branca. Glenn had his collar pulled up and his ducktail and he looked super fucking cool and the other one was this guy David Rosenbloom who was later in Glenn’s band with me. The guy in the middle playing just a hi-hat was this guy called Wharton Tiers who recorded a lot of the early Sonic Youth records and Glenn records too.

They played ‘Guitar Trio’ and it was a half an hour long, just open tuned guitars and it just built to this absolute roar. It was kind of an amazing experience, it was so incredible sounding and it was one of those pieces that you hear and think ‘wow, I’ve heard this in my head forever and I’ve never heard it in real life, and here it is right now in front of me.’ It was really amazing on a lot of levels. The piece ended and they were in this period where Rhys was really into this drug called amyl nitrate, you’d take a sniff and for thirty seconds your head would explode. So they were doing that during the piece and in between the pieces, and after the piece was over they were all in a huddle and you could tell Rhys was doing amyl nitrate. Then he stumbled back to the foreground and said “we’re gonna do another number now!” and they proceeded to do the exact same number again for another half hour and this time they had these enigmatic slides projected by Robert Longo who became a famous artist later. It was a crazy, crazy night and it introduced me to both Glenn and Rhys.

The first place I moved to a few weeks later, with David Linton, the drummer in my band The Flucts, was this cold-water loft in Brooklyn. Across the hall was a keyboard player called Anthony Coleman who was still a downtown fixture. He said come and play with this guy Glenn Branca and slowly we worked out that’s who that guy was on stage with Rhys that night.

Coleman said you should come down and see us we’re playing at the Kitchen or whatever and Glenn was supporting his first record which was called Lesson No. 1 for Electric Guitar. We went and saw it and it was again one of these evenings where it was unbelievable, I’ve never heard anything like this and I’ve always dreamed of this kind of music. And he had another artist with him called Richard Prince who did the artwork on my new record.

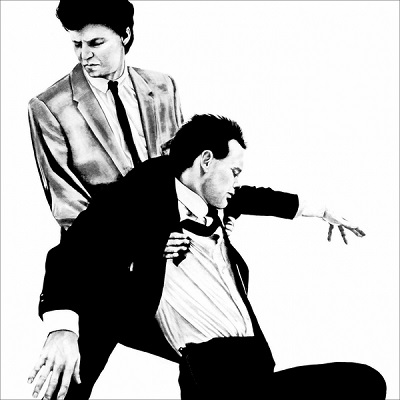

One of the pieces Branca did was called ‘Dissonance’ and it has a part for a sledgehammer on an anvil, and so Richard Prince was playing that. This was at the Kitchen and it was four guitars and a bass and drums and Glenn was leading the group like a deranged Toscanini, his back to the crowd, his guitar slung low, the pompadour and the collar and everything. He always had clothes that were ripped around the edges so he looked half like a street bum and he was conducting.

It was really remarkable and a couple of weeks later he put an ad in the Village Voice, which said he needed musicians for his new record and tour. In the interim I had actually played ‘Guitar Trio’ with Rhys Chatham and Glenn was at the show and saw me, so when I went over to his house he recognized me right away and he taught me the parts and said this is the kind of stuff it’s going to be, do you think you can do it and I said yeah.

So we started to build this really tight relationship and it led to the recording of Glenn’s The Ascension which was really like Glenn’s coming out. It was bigger than a pop group, it wasn’t two guitars any more, it was four guitars and he was on his way towards making these rock symphonies. Some writer, I don’t know if it was snarky or not, wrote “well it was 45 minutes long and it sounded like the last 3 chords of a Who song”. To me that sounds like the ultimate experience. I don’t know if the guy was chiding him or not but often that was a pretty apt description. You could substitute Beethoven for The Who or something – they all use the same chords and yet it had that amazing quality and it was also very, very loud and we worked together for a number of years and in a way on stage I became Glenn’s foil.

We started to get into these guitar duels together, rubbing the guitars together, rolling around on the ground and all that stuff. In a certain way he’d found someone that was like minded enough he could actually take it into this other level. Glenn’s whole thing was, and he grew up in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania where this whole Three Mile Island thing was, he was a drama person. He went to school in Boston to study theatre and he was making these experimental theatre pieces and he needed music for them and he couldn’t find the right music and so he started making the music for them and it just transpired that he got more interested in the musical side of it than the theatrical side of it and so he always had an eye for the drama of the music.

I couldn’t say enough about how important and extreme as the music was, he was never unaware of this dramatic element of what he was doing. It was always staged in a way for maximum drama. There was always maximum drama whenever Glenn was in the building, whether there was an argument, or the music, or a discussion about high art or whatever it was. Branca was so responsible for so much stuff, for energizing this down town scene in a major way.

He was one of these artists that you didn’t really experience his music unless you were in front of it. You could hear the records and The Ascension was some of his best work ever and it’s a great record but it didn’t sound anything like what it sounded like to stand in front of it at 110 decibels.

He also started his own label and released a couple of the first Sonic Youth records. He asked us to be the first release on his label so there was kind of a mentoring thing going on there as well. It was definitely some of the most important music that was going on in New York at that time, because it was straddling all these worlds. It had one foot in the punk world, one foot in the art scene and then in the Phillip Glass, Terry Riley, Steve Reich kind of world of art music, he had elements of all of that stuff, and beyond all of it, just what he was doing was brilliant.