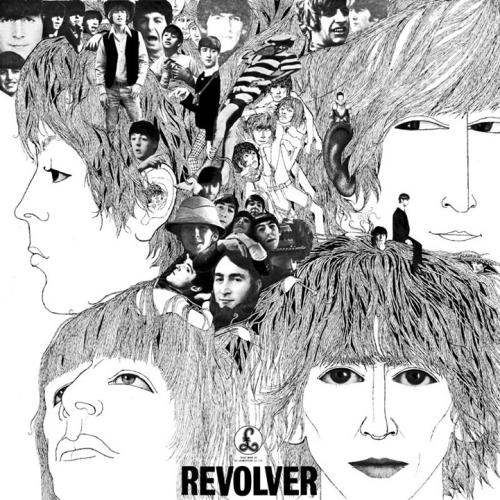

4. The BeatlesRevolver

I was in an all-night art school party in Coppull, Lancashire. One of the revered second-year students brought in a copy of Revolver – new Beatles record, just released. We sat around and played it all, as one did in those days, listening to messages from another planet, soon to be our own. The local copper came in off his beat and settled down for a couple of drinks. All the beautifully crafted songs floated by in 4D – then, right at the end, we heard ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, and that was it – forget the rest. We played that one all night, time after time.

It wasn’t like anything else we’d ever heard, but somehow seemed instantly recognizable. Sure, the words were a bit suspect, but the music, the sound – organic electricity, disintegrated transmissions, lost radio stations, Catholic/Buddhist mass from a parallel universe, what being stoned ought to be like – weightless, timeless, revelation, moving over luminous new landscapes in serene velocity. It communicated, innovated, infiltrated, fascinated, elevated – it was a road map for the future.

I realised much later that it contained a basic kit of almost everything I’d need to make music for the rest of my life – drones, chants, drum loops, bass beats, random sounds, reversed tapes, vérité recordings – and best of all it sounded nothing like the blues or american rock & roll. Much as I loved all this, I felt it was way out of my experience. You could admire it, but not imitate it without feeling a bit daft. So this record was also a great liberation in that sense, too. Another point to make about this track is it is impossible music – music you could never play live. It was a creation of the recording studio, and that was also liberating and revolutionary. As an art student I was becoming aware of that aspect of studio work, and loved it – all those possibilities of choice in the combination of inspired, momentary gestures, even accidents, with incremental, finely-judged work.

Much later, I read how George Martin had literally thrown in the random tapes, noises and reversed sounds after being engaged by new ideas from Stockhausen, Schaeffer and others making the new musique concrète. Martin was a sonic genius right up there with Lee Perry and Conny Plank. In that single move, before anyone else, he used tape as a music-making medium as well as a recording medium – a shift that laid open an entire new universe in popular (or any) music. He changed the future of recording, as well as the sound and the possibilities of popular music, in that moment.