7. Blackstar Featuring Top CatChampion DJ

The aforementioned Britpop historians rarely mention that many of us were listening to all sorts of wilfully different music alongside it; it was less a case of Blur vs Oasis, and more a case of Big Black vs Rancid vs Lee Scratch Perry vs New York Dolls. And for me, hearing early jungle was as exciting as when I first saw that footage of Iggy Pop doing ‘The Passenger’, with a horse’s tail attached to his rear. It was music from another planet, and I wanted to know more.

My sister was living in a squat in Kennington, so from the age of 15 I began to make many deep forays into London life, travelling down to spend two weeks wandering London on foot – visiting every single record and book shop and undertaking mini-pilgrimages to places of pop significance. I’d head off to Soho, Notting Hill, Brixton and Camden with a notepad so that I might jot down some observations: the sights, sounds, smells… drains, fried chicken and BO, mainly. I didn’t realise it at the time, but I was taking further tentative steps towards becoming a writer.

Somewhere along the way I heard early jungle, which circa 1993/1994 was essentially ragga music reborn in London: fast, furious, really hard to dance to and not made for white boys from the north-east who probably resembled a member of Supergrass. I think it’s important to get out your comfort zone now and again.

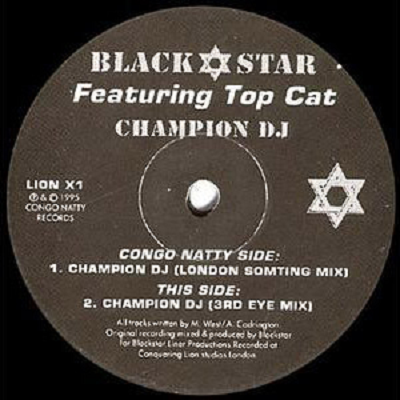

I could have chosen ‘Original Nuttah’ by UK Apache with Shy FX but I was utterly obsessed with ‘Champion DJ’ after my sister’s then-boyfriend played me it. Blackstar was Michael West, aka Rebel MC aka Congo Natty, who’d had a hit with ‘Street Tuff’ by his early band Double Trouble. In fact, he is credited with spawning the term jungle. But it also features a sample from The Revolutionaries’ ‘Kunta Kinte’, which was recently used to spellbinding effect in Steve McQueen’s ‘Lovers Rock.’

When this song kicks in at the fifty-second mark it makes me want to shoot guns into ceilings, and it represents a period when life was semi-feral, and music no longer had to be tribal or parochial. You could listen to everything. I tried to spread the gospel by taking this back to Luton and playing it to my indie-loving friends. I think they thought I was just trying to be eccentric or contrary, but my love was genuine.

Years later when jungle and garage had a baby and called it grime, I was on board with that too.