Anni Hogan was one of the first female DJs and promoters in the fecund post punk ferment of Leeds and London. She spread her infectious enthusiasm for electronic music, northern soul and smoky dive bar jazz in equal measure at the pivotal Amnesia and Batcave clubs, while manning the decks and booking the talent.

Her earliest forays into music were revelatory turns with Derek Jarman-soundtracker and avant-garde innovator Simon Fisher Turner; nascent Bad Seed Nick Cave and big band swinger Barry Adamson. She was part of a heady scene that revolved around a houseboat in Chelsea and included likeminded spirits Lydia Lunch, JG Thirlwell and Blixa Bargeld not to mention Siouxise and The Banshees. Through experiments in sound and technique, Hogan developed both her songwriting skills and a fluidity on the piano which was akin to catching moonbeams in a jar: the results can be clearly heard on her iconic Kickabye EP of 1985.

It’s for her formative collaborations with Marc Almond that Hogan is perhaps best known – a friendship begun on the Amnesia dancefloor that blossomed through Marc And The Mambas, whose members included The The’s Matt Johnson and the multi-instrumentalists Martin McCarrick and Billy McGee and whose inspiration came from Jacques Brel, The Velvet Underground and Syd Barrett. Post-Soft Cell, she continued as Almond’s musical director, co-writing and performing as part of The Willing Sinners and then La Magia, for whom she co-produced 1989’s The Stars We Are album that contained the smash hit duet ‘Something’s Gotten Hold Of My Heart’ for Almond and Gene Pitney.

Continuing her quest for musical enlightenment on collaborations with Yello, Kraftwerk’s Wolfgang Flür, Zeke Manyika and Swans’ Jarboe, she has also played with such legends as Hugh Masekela, toured with Paul Weller and formed the acclaimed Cactus Rain along the way. She has scored films, including 2012’s Mountain with Rob Strachan, which she also produced; co-founded the Mitra Music for Nepal project with Cathy O’Dowd in 2015 and released the 2016 electro-acoustic album Scanni with Scanner. More recently, she formed the ZANTi project, with Derek Forbes of Simple Minds and Propaganda and their Broken Hearted City album was released earlier this year.

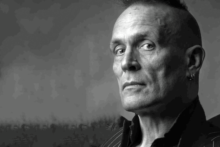

But perhaps now the wheel of time and fortune has spun back around: Hogan’s latest album Lost In Blue brings back many voices from her past to meet in a candle-lit, smoky basement dive, with a distinctive figure at the piano. Lydia Lunch, Richard Strange, Wolfgang Flür, Kid Congo Powers and Gavin Friday provide richly evocative contributions to a dreamlike, celluloid soundtrack, fashioned with the help of producer, Dave Ball. Both as a requiem for times and places lost in memory and a celebration of the spirit that defies adversity, it is a profoundly beautiful journey to the end of the night.

You were initially known as a DJ at the Amnesia Club in Leeds. Presumably being a woman behind the decks was a rare sight back then?

Anni Hogan: Around the same time as I started as a DJ, I’d actually semi-joined a local unknown, never-to-be, Leeds band with the terrible moniker You The Night And The Music. I never actually played an instrument or did any gigs but went to several meetings until they disbanded a few weeks later. But they did affect one transformation: Julie, one of the girls in the band, wanted to try tinting my hair blonde and spiking it up, which I was very into. It was at that point I could visibly see myself changing – which echoed the change I was feeling inside, really. I was extremely affected by all the new electronic music I was hearing. I had seen Joy Division supporting the Buzzcocks at Leeds Uni in 1979 and they made a huge impact on me. I went to the second Leeds Futurama and was stunned by Soft Cell’s unique, manic performance. So I was certainly having my own cultural shifts.

I started working at the Amnesia in the summer of 1980 I think. All the students had gone home and although I was from Merseyside originally, I stayed on afterwards, taking an endless year out of university, as I felt more at home in Leeds. At first I got a job behind the bar and through that I struck up a friendship with the in-house DJ called Ian Dewhurst. At this time, I was coming into contact with the wilder and weirder characters on the Leeds scene. There were a pair of girls who wore tweed suits and twinsets and they had played me Reproduction by The Human League for the first time which blew my mind. Ian reacted to my perpetual requests for alternative music by getting me to DJ while he went for a drink, but as I quickly got more experienced, he encouraged me to play for longer and longer while he chatted up women, paying me with cocktails and cigarettes. This situation suited everyone.

It never occurred to me that being a female DJ was such a big deal. Thinking back, it was radical and pioneering, but for me personally, it was a natural progression from making mixtapes on the cassette player when I was young or putting the 45s in a certain play order on my record player. It’s always about the music for me.

Eventually I began running my own nights. Ian turned me onto a lot of great music too, US disco and northern soul and I was able to incorporate my own eclectic tastes in music into my own nights.

At what stage did you start to promote gigs there?

AH: Jeff, who was the manager, eventually put me on the books for the princely sum of seven quid a week. I wasn’t promoting or booking bands in a conventional way, but Jeff knew I had, shall we say ‘cool’, current taste and he wanted me to get the bands in that I wanted to see or I was hearing exciting things about. Depeche Mode, A Certain Ratio, and of course, Soft Cell were among the acts that I promoted at the club.

When did you meet Soft Cell?

AH: I first met them out in Amnesia, they used to come down to my nights. There was a room going at a place in Leicester Grove, a rundown, cheap housing area of Leeds where Marc and Dave lived. So I took the room and we became flatmates and friends. One time I went into Dave’s room and Petula Clark’s ‘Downtown’ was playing through his synths; he was doing this amazing remix on the spot. I think it was then that I really felt something special was happening and could sense that the shift from the traditional rock line-up to the economy of electronics was happening. Dave was actually so ahead of the game back then it was crazy. He used to take his drum machine to the Warehouse and jam over the records and people used to think they were hearing special remixes, this was in 1979 or 1980. Marc was of course an amazing, beautiful creature, he was at the centre of everything.

Were you surprised when they found success?

AH: Not at all, I was such a fan anyway and had seen them many times up to that point, they actually did ‘Tainted Love’ for the first time live at a show I promoted at Amnesia. We all knew, in Leeds at least, that they were going to be big – maybe not as big as that record eventually became maybe, but they certainly had something special and unique.

Was it at this stage your started to get more involved with your own music?

AH: At some point during late 1981, I met Matt Johnson, most likely at the infamous Columbia hotel in London, where record companies put bands while they were in the capital. Matt and myself hung out a lot for a time. I must have told him I played the piano and he then put me in touch with Simon Fisher Turner who was absolutely wonderful. We went into the studio and I did an improvised piano piece and string synth part to recordings of clockwork dolls and all sorts of strange sounds. It was my first time ever in a studio. I must have had it on tape and then played it to Marc. He was surprised, I think, as I’m not sure he knew I played at that time.

On the strength of that, presumably he asked you to join the embryonic Marc and the Mambas?

AH: It was never really like that. He bought a house in Leeds and asked me to move in. We lived together there while Soft Cell continued. We recorded ‘Sleaze’ and ‘Fun City’ with Dave and Tim Taylor for a Soft Cell fan club 12” at Box studios in Heckmondwike in Yorkshire. It was just a fun and easy experience to be in the studio with my friends and making music. I had no doubts and improvised on electric piano, even throwing in a bit of Duke Ellington’s ‘Caravan’ on organ over the end of ‘Sleaze’. We posed for the sleeve band photo with Huw Feather and the record came out. I think Marc realised I was very musical and was someone he could work with as an alternative to Soft Cell and so the Mambas became a more realistic longer-term venture than maybe was initially thought.

Did that freedom of expression follow into the recording of the first Marc and the Mambas full length LP Untitled?

AH: In a sense, yes. Matt Johnson worked with Marc for two tracks on the album, ‘Angels’ and ‘Untitled’, with me playing the piano line on the hugely underrated title track. The other tracks were either more or less improvised or arranged by me. ‘Empty Eyes’ was very much an on-the-spot track I came up with on electric piano and developed from there, and I think Marc and Cindy’s backing vocals added a loose, 1960’s girl group feel to that track. It was that Velvet Underground-influenced psyche which underpinned many of the tracks and gave the album an overall psychedelic feel.

Marc was so brave with his song choices and the project as a whole. At the time, Soft Cell basically had a teenybopper audience so to choose Lou Reed, Jacques Brel and Syd Barrett covers – and even encourage my solo pseudo classical piano piece – must have split his fanbase at the time. It’s easily my favourite Mambas album.

What changed between the recording of Untitled and Torment And Toreros?

AH: I’d been a DJ for Soft Cell during The Art Of Falling Apart tour and it had been such a positive and happy experience despite the inevitable arguments and drama of being on the road. However, the pressure of being a big act was starting to take a toll and none of it was helped by their manager Stevo, who could make a tense situation impossible. He seemed to live off the drama, but to be fair, he was only about 19 years old at that stage.

Lots of this tension carried over into the recording of Torment. All of a sudden it was no longer just me, Marc and Flood (who had engineered Untitled too) it was a whole new lot of faces, with all of them vying for Marc’s attention. Looking back, I suppose I was a bit jealous and intimidated by these trained Guildhall musicians. We recorded it at the famous Trident studios, it was done mainly at night. Really long hours and it really tested us all. It was an emotionally draining experience for me.

Did you love Marc?

AH: I’ve always loved Marc, I have never stopped loving him. I don’t really work like that. I certainly have felt hurt by him and am sure I must have done the same [to him]. I think I saw him as a big brother and I was his pain-in-the-ass little sister. We were both very insecure people and artists. At the time I was very young and there was extreme pressure… the experience of making that record wasn’t a happy one for me. I felt, and still do, that Marc and myself had a very special musical dynamic but we took everything to the limit on Torment.

How did you come to work with Nick Cave?

AH: By 1983, I had moved to London. I stayed at Lydia Lunch’s place briefly while she was back in the States and this coincided with me making Kickabye in Alvic studios, only a walk away from Lydia’s. I had friends called Christina and Celia who lived on a houseboat in Chelsea Wharf and they were also friends with Nick, Kid Congo, Barry Adamson and the wonderful Jessamy Calkin who was tour manager to Einstürzende Neubauten. Nick and I wrote a song called ‘Vixo’, which listening back now, was pretty much him discovering himself and where he was about to go as a solo artist. I also played on the demo of his version of ‘In The Ghetto’. It was just the way it was back then, we were all just constantly working and helping each other out.

I also played on the backing tracks for the Immaculate Consumptive live shows. I had befriended The Banshees, Sioux, Budgie and Steve all helped me out, and their driver at the time, Jos Grain, who now does live production for Iggy Pop. I got asked to be a regular DJ at the brilliant Batcave and Jos used to drive me from Lydia’s and along with the Banshees, Blixa Bargeld, Nick, Lydia, Jessamy, Marc and the guys regularly came down. It was the place to be and the atmosphere was a heady heat and intoxicated brew of crazies mad for the music. Danielle Dax, fresh from The Company Of Wolves, was naked and painted in the cage, the whole place was decorated, they had a cinema/sex room with Hamish DJing downstairs and me upstairs. Fascinating times. The Batcave was the best!

Marc and I did play the Batcave using backing tapes and Farfisa organ. It was pretty brave of him/us but I remember thinking, ‘We are great, we are the natural progression on from the Velvets’ – well, I was excited and in the moment! Then I’d go back to Lydia’s flat and take Pervert the poodle for a walk and feel genuinely inspired by everything going on around me.

Lydia had left her records so I quickly discovered new records and sounds, for example Yma Sumac’s magnificent Mambo! and John Barry’s Beat Girl. I played them all down the Batcave and back in Leeds, when I went up there. Lydia’s Queen Of Siam remains one of my all-time favourite ever albums and was also played to death in my DJ sets.

It’s quite an impressive list of artists that appeared on the Kickabye EP.

AH: There was a strong female presence on the EP. Jessamy Calkin wrote the lyrics to all the songs (except ‘Vixo’) including ‘Burning Boats’, on which Marc Almond gave one of his great vocal performances. Anita Lane, who was still with Nick at the time, came up with Kickabye as the title for the EP. Gini Ball and Anne Stevenson, along with Billy McGee, provided real strings, happily playing their real string arrangements of my crazy keyboard played string parts… it worked out great! Aside from that, Budgie from the Banshees drummed and played harmonica on ‘Vixo’ and my vocal tracks and Jim Thirlwell gave some extra Foetus treatment to ‘Burning Boats’, although everyone worked to my original piano parts which I always laid down first, even before the drums, something I still tend to do now if I can get away with it. I like to drive the pieces myself, basically.

By 1984 Marc Almond had disbanded the Mambas and Soft Cell had split. He formed the Willing Sinners, a new group based around yourself and your fellow Mambas Billy McGee and Martin McCarrick. How did your working dynamic change at this point?

AH: I think because we had been working together for a while by then, we just felt it was a natural progression. We didn’t realise the pressure that Marc was under, to be out on his own. I certainly didn’t really understand the nature of the business then: money spent needed to be recouped. The full nature of the music industry manifesting as beast of burden [when it came to] the solo artist could be very damaging to anyone who came into contact with it. It was a truly stressful experience. However, in the end this was his choice and we still did rally round him and work very hard ourselves against this stressful backdrop.

The first two Willing Sinners albums were recorded at Hartman Digital in Bavaria with Mike Hedges. It was emotionally and musically a very mixed experience. For example, Mike took an instant dislike to our guitarist Richard which made it a bit tense and I was the only girl most of the time. I have the impression Mike tried to divide us, possibly under record company orders, to treat us like session musicians essentially, which was a shame as I felt for once this was a real happening band. A band that toured, made records and, at that point, hung out together. We were also tight and had great talent in the ranks, I mean Billy, like myself, worked with Nick Cave and Barry Adamson and Martin went on to be in the Banshees, while Steve played with Echo & The Bunnymen.

The actual recording process with Mike wasn’t really too bad for me, we got on in general, shared a passion for some similar sounds and he was a funny guy. He loved the piano and used a version of the ‘wall of sound’ method on his production with the piano doing well in the mix. I actually loved living at the studio on a day-to-day basis and found it very stimulating. We were in the mountains, with use of a sauna that utilised a stream as it’s cold room, for God’s sake! I stayed over during a holiday break and met Yello and did an impromptu guest piano improv on a typical rhythmic wild ride of a track by Boris, called ‘Blue Nabou’. Again, I was a huge fan, so this was a special moment, too. I was hanging in the screen room watching a film and had been relaxing, to put it mildly. They just popped their heads round the door and asked if I wanted to play on this track. Of course I did!

In the end, there are some amazing songs on Vermin In Ermine and Stories Of Johnny. We even had minor chart hits, but it was on the next album that I feel we truly created something extraordinary.

Mother Fist And Her Five Daughters is widely regarded as Marc’s finest solo work, but with little commercial potential due to the themes such as masturbation and suicide. How did you approach working on that project?

AH: It was such a productive period and we actually had enough music for a double album – in fact I think that was the original idea before the record company got wind of how it sounded and the themes Marc was singing about. We got back to a very minimal sound on that record and it has an almost 1930s blues feel mixed with Weimar cabaret. It was a record that Marc needed to make and it just flowed out of him as it did out of us.

I had much more input on Mother Fist co-writing and arranging the album. It was experimental and yet musically still very accessible and humorous, too. We used lots of authentic, interesting instruments we had heard on our favourite records: real marimba, vibraphone, hurdy gurdy, yang ching, harmonium and so on. This hive of intense musical creativity made for a beautifully-crafted record, which is for me the best representation of The Willing Sinners. Mike Hedges was again on production but we recorded in the UK this time and in my memory, it remains a far superior experience to the making of the previous records in Bavaria. But we were older, wiser and more experienced, so that does make sense.

And then Martin McCarrick left to join Siouxsie and the Banshees.

AH: We had just finished a big tour and he announced he was leaving. I was devastated, we all were. There was a big connection between us and the Banshees and I felt there was a certain amount of seducing going on from the Banshees side – previously, they had spent time with me and I have since thought maybe they were thinking of asking me. Sioux and Budgie had helped me during the making of Kickabye and Steve was also a mate. I even appeared as the sleepy dormouse in their Play At Home special on Channel 4 alongside Robert Smith. I remember Budgie criticising Marc’s vocal technique to me and I did not like that. I could never imagine leaving Marc, so the next obvious choice from our stock was brilliant multi-instrumentalist Martin McCarrick. I think he was probably feeling it was time for a change.

You worked with Zeke Manyika from Orange Juice on his solo album and also on Barry Adamson’s immense Moss Side Story. How did these come about? Did Marc react to these collaborations? What else did you do off-road from Marc ?

AH: No, Marc was supportive at that stage, maybe he thought if I did a few different smaller things… who knows. Zeke drummed a bit with Marc and we hit it off, we started trying the odd thing out musically and in the end I worked on Zeke’s solo album and a couple of 12”s, while he produced a couple of early solo tracks for me which ended up on the Kickaby reissue. He also introduced me to Hugh Masekela and I was very fortunate (and a bit overwhelmed) to be asked by Zeke to perform a solo piano support slot for both of them at the Africa Centre. It was a biggie in my heart. Yet another genius trumpet player.

Barry Adamson was a big influence before I even knew him. Magazine were huge for me. I saw them at the Warehouse, possibly with Simple Minds… which, if so, means I also met another great bass player I have since worked with, my Zanti band cohort Derek Forbes, Ha! That is great!

Between hanging with the Banshees, meeting Kid Congo at Gun Club gigs and hanging with Blixa from Neubauten, my musical antenna must have been on excitement overload. I was also the DJ support at some interesting key events: Neubauten at Heaven, Test Department and Diamanda Galas at Under The Arches and a few private Some Bizzare parties, including The The, Coil, more Neubauten, and the closing down of the GLC party.

Meanwhile on the houseboat, Barry was seeing Celia. He bought a Mirage keyboard and started writing furiously. I was intrigued and of course into it. When he finally got into a studio, the superlative ‘Man With The Golden Arm’ was the stand-out amazing track with Enrico Tomasso on trumpet, Billy McGee on double bass and I did the Bernard Hermannesque string line. I also played vibes on another track ‘The Most Beautiful Girl In The World’. Barry has recently released his career-spanning anthology Memento Mori and ‘Golden Arm’ is on there, to my personal delight. So I was dipping my toe into other possibilities, early collaborations, but still remaining with Marc.

So what came next was quite a surprise: the critically acclaimed The Stars We Are album that contained the Number 1 hit ‘Something’s Gotten Hold Of My Heart’ with Gene Pitney.

AH: When Martin left, Marc reinvented our band as La Magia, with the core of me, Billy McGee, and Steven Humphries. I felt very involved at this stage and fondly remember Billy and I working so hard, night after night, on arrangements and on the music. It felt very stimulating; it was a liberating experience, as well a a huge challenge. The single ‘Tears Run Rings’ charted and we even did Top Of The Pops, Marc looking the part with an amazing quiff. When it was becoming obvious that ‘Something’s Gotten Hold Of My Heart’ was going to be a major hit single, I was not only crazy elated for myself but also happy for Marc, because I think it allowed him to finally prove the doubters wrong. After all, it was all on his head, and he had the pressure of it all. I have a silver disc for that album, a gold disc for ‘Something’ and of course Marc, me and Billy co-wrote and produced the album.

What are your memories of the Nico duet on the album?

AH: It was pretty intense, unsurprisingly, she wasn’t fully with it for whatever reason and she kept mistaking me for Mo Tucker and thinking she was in the studio with the Velvets, time travelling away in her head. She had trouble locating the microphone, too. It was a little depressing but also completely insane and exhilarating. Despite this, she delivered a spine-tingling vocal and, along with Billy’s string arrangement, the track was one of the album’s highlights.

The Stars We Are proved to be the last record you made with Marc Almond after a nine-year period. Why was that, when you seemed to be at the height of your combined powers?

AH: It was a combination of many things. I think I felt I wasn’t getting the recognition for my work and things blew up into something that never needed to get to that stage. Marc and myself never had proper talks, things always got dramatic for no reason. If we’d had a level head within the set up at that time, I think things would have worked out different. I think the whole dance thing was really making an impact by 1989 in the charts, and certain people who had Marc’s ear were trying to advise me and Billy on how to arrange our stuff, strip it down for clubs, and it just went against the sound we had built. It was a negative influence, confusing and destabilising.

I think, however, my ill-fated solo project Cactus Rain may have brought it all to a head. I had been on tour with Paul Weller previously, which was an awful experience, the worst of cod rock imaginable, bass solos at the front of the stage… the kind of thing I was totally unused to. So I didn’t think starting my own project would be too much of a problem. I got a huge advance, one that I’m still paying back to this day, and recorded it at Blackwing studio with Eric “Upstairs” Radcliffe. I don’t have any regrets; to me, all roads lead to now, and I am very happy these days. But I think it was probably my biggest career mistake.

We were at the height of our musical powers, I would have been better off to stay with Marc; I should have stayed and supported him and so on, but things were highly emotional on all sides. Things got very intense on all fronts. I was still fairly young, and faced with confrontation, I went the other way.

In the end, I never wanted to leave Marc because I felt I could do both projects but he did not like it one bit and I imagine also thought what the fuck was I even thinking. I just had to try it out, I guess. It did not turn out well but it was a huge learning curve and I still wrote some good material, worked with the Reggae Philharmonic and had great fun working with my keyboard and jazz pianist pal Mark Edwards. We had met on tour with Paul Weller and sneaked off to have joints and share all our favourite music with each other making mix tapes. Mark’s trio supported Nina Simone in Brighton and he actually introduced me to the mighty musical Goddess, so there were always good things among the turmoil. I also worked with Arabella Rodriguez, which was inspiring, she engineered the Soul II Soul album and I loved that and asked for her especially.

I just did not understand what it took to front a concept like Cactus Rain and, with the benefit of hindsight, of course I would have done things very differently. However, for me, life is about dealing with the mistakes and learning from them and moving forward, or making the same mistakes again until you don’t, I guess. I’m a lot more philosophical these days about all those past musical jaunts.

You never stopped working and collaborating though. In recent years you have done projects with artists as diverse as Wolfgang Flür, ex-Kraftwerk, and Derek Forbes from Simple Minds/Propaganda,. You contributed to another track on the latest Simon Fisher Turner Deux Filles album and a been part of a large female collaboration involving former Swans musician Jarboe. How important is it for you to work with artists like these?

AH: Well for a start, if I work with people I already know are brilliant and experienced then of course that allows for proper top work; and that really is where I function at my best. It’s the old adage that the really great people make you push the very best out of yourself. I do this by collaborating with people I think I can work with, that I connect with in one way or more, whether it is historical, a chance meeting, or installation ideas. Someone I admire that I think I can also bring something musically to the table. I have to not be insecure and just focus on the music or film and what I can do.

I have been fortunate to meet some incredible people along my musical path, people I have worked with regularly over all the years ,often seeking them out as similar souls, sometimes just happening by fate. For example, Wolfgang Flür was a chance meeting which I followed through; Jarboe I have known since the 1980s. With Derek Forbes, it was entirely new, but we had immediate connection in the studio, writing, arranging, singing, producing and playing everything, an ultra-enriching experience of the highest order. Collaborating is generally the nature of my work, opening up some hidden musical places inside me which is always exciting and I’m also enjoying working in audio-visual conceptual installations as part of my work output.

Which brings us to your new album. Produced by Dave Ball and again featuring a host of guests, does it feel like you have come full circle?

AH: In a way, yes. After spending a lot of time writing and collating material in quite a reclusive creative process, it’s been a wonderful experience to have connected with a number of artists from my own past and present, including Dave Ball, Lydia Lunch, Gavin Friday and Kid Congo, among an incredible line-up. Everyone involved on Lost In Blue gave their amazing talent and we all had a shared empathy for the music, and each other’s work. A wonderfully uplifting and positive experience for me and I personally hear it coming out of the darkness from the record. It was also fantastic to work with one time Mamba and photographic icon Peter Ashworth for the sleeve artwork, too.

So, where next?

AH: The next project is always on the horizon and of course live performance scenarios are becoming a serious consideration too. Installations, collaborations, promoting my new albums, all the usual subjects.

Lost In Blue the new album by Anni Hogan is out on March 8 via Cold Spring