There’s often no prize for coming first in music. The preternaturally talented composer, ear-boggling singer, intuitive multi-instrumentalist, vocal manipulation innovator and pioneering synthesizer early adopter, Annette Peacock knows this more than most. During an interview she tells me that every time she makes an album she feels like it’s the right statement for the time but it turns out never to be the right statement for the market of the time. Markets are big amorphous, slow moving bodies that perhaps don’t always respond well to mercurial outlier innovation in music. "I feel like I’m doing the right thing at the right time but then it turns out I’ve been 20 to 40 years too early", she says laughing.

Though it seems unfair to Annette herself, at least it’s a guaranteed revelation for music fans today who stumble across her work as it still sounds incredibly fresh all these decades later. If you’re anything like me and listen to any version of her track ‘I’m The One’ you’ll have your mind blown by a colourfully cosmic clash of pitching and yawing MOOG lines, stone to the bone funk rhythms and a stunning mix of soulful singing and muscular vocalisations, blasted apart into pure pointilism by electronic manipulation. It is as smooth and seductive as it is raw and urgent as it is spacious and minimalist; and still, four decades later, it sounds like a version of future music that is yet to fully arrive.

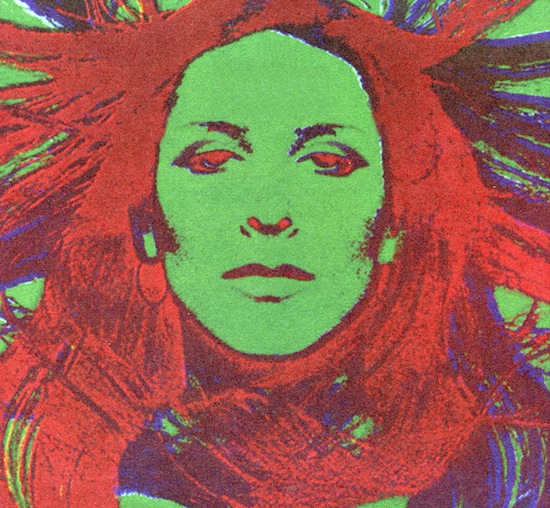

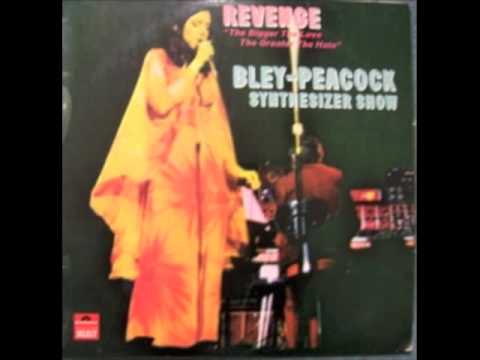

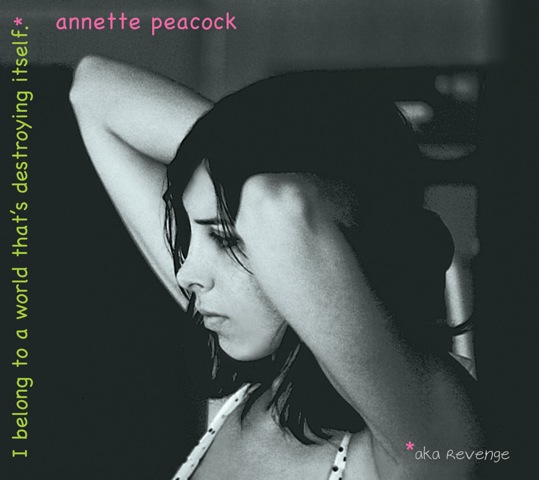

However, a new generation is starting to wake up to her undeniable power. Aiding this process of rediscovery has been what one can only hope is just the start of an extensive reissue programme. In 2012 Future Days reissued her marvellous I’m The One album from 1971 (after Annette had released the signed, collectors edition on her own label). Even though, like most of her albums, it defies easy categorisation, it is a bizarre and rewarding blend of psychedelic funk, synthesizer embellished jazz, singer songwriter balladeering and futuristic blues. And now this year her own Ironic label is about to reissue the Bley-Peacock Synthesizer Show’s Revenge: The Bigger The Love The Greater The Hate (recorded in 1968) as Annette Peacock’s I Belong To A World That’s Destroying Itself. This record is an even rawer, wilder prophetic warning of ecological disaster, that features a trail-blazing use of synthesizer-modulated vocal takes and is the first recorded examples of her pioneering free form song style. (One can only hope that X-Dreams and The Perfect Release get the reissue treatment soon as well.)

Born in New York in 1941, she was composing music and experimenting on the family piano before she even started at school. She had the life changing experience of taking LSD under the guidance of Timothy Leary in the early 60s and toured with Albert Ayler’s band when she was just 20 years old. The pianist Paul Bley began to record her compositions in the mid 60s and eventually they would feature on over 60 of his records. After hearing the Walter Carlos album Switched On Bach she became determined to be the first artist to record what she saw as serious new music using the new instrument as the key element and went to visit Robert Moog with the express intent of persuading him to gift her a prototype of one of his machines; something she managed to do.

Being such an outlier musician, determined to give no quarter to commercial interests, has led to her going through several long periods where she hasn’t released albums, perhaps another reason why she isn’t yet a household name. However with these recent reissues and the fact she is now working on a new album, one would hope that more and more people will have their ears opened to her unique musical vision.

You come from a musical family. Do you feel like you were born to make music?

Annette Peacock: I’ve often wondered about that. I’ve often wondered about how much of that comes to you in utero, or from your DNA, or from your environment… it’s never been determined basically. But yeah, there were string quartets playing me to sleep downstairs at night. My mother played in the philharmonic orchestra so I was always taken around to the rehearsals and always hearing music constantly. There was a piano in the house and I was left alone a lot. Inevitably I began to make sound using the piano; as a toy even. As a child you strike it and it makes a noise – the possibilities are infinite. It’s not a fixed programme. You have all of these notes and don’t know any of the relationships between them, so it’s fascinating to a child.

Do you remember what the earliest songs or compositions that you wrote were like?

AP: No I don’t but what I do remember is that I wanted to study piano and I had a friend who was being classically trained by her father. She was kind of an older role model for me and this kind of spurred me on to want to learn the piano. So I begged my mother for music lessons and instead of being able to play pieces – I thought, ‘Oh, I’m going to be playing the piano and all of these beautiful pieces’ – they gave me scales. I had to play these scales over and over again. And I was really really irritated. And then when they gave me the first piece of music I hated it and I refused to play it so my mother said I couldn’t continue with the lessons. So I was left to explore the piano on my own which may have worked to my advantage.

At most of the stages in your life you have been self-taught haven’t you, apart from one brief period in a musical conservatory.

AP: Yes. That seemed to be the way it was going. I was with two musicians who had been trained. Paul [Bley] had been at Julliard and Gary [Peacock] had been trained. Neither of them would teach me. Paul said I would lose my originality and maybe he was right. When you think about it, when you’re exposed to all of the amazing music that has been made before you, how could you possibly conceive that you were going to make something equal to what had already been created? I wasn’t trained to hear music in a traditional way so it gave me the advantage of being able to hear in a pure sense without any foundation of perspective or anything like that. So the whole process was very open for me.

From a very young age you were associated with some very far out countercultural figures. What influence did Timothy Leary have on your outlook on life?

AP: Well, two things. One, I asked him what he hoped to achieve with LSD and psychedelics and he said he hoped to influence the arts. You know I only ever took one LSD trip and I don’t think I ever really came back from it! I’ve been fighting my way back into reality ever since [laughs]. But it certainly put that idea in my mind that the two things could be connected: the psychedelic state of mind or perspective and the sound. So I think that influenced me. It was very memorable. And he called me a love goddess. I met him at some friends’ houses, who were comrades of his when he was at Harvard. I was at one of the houses when he came round for dinner and he invited me to come back to Milbrook [the rambling mansion that Leary and his associates operated from] that evening. He relinquished his bedroom, he was a perfect gentleman; he was absolutely lovely and I ended up staying there for quite a while. We didn’t have any kind of intimate relationship because I’m not that sort of person. I wish I was more sexually liberated and had been with more people but I’m kind of a private person. But the concept was kind of interesting and I hadn’t heard that before.

Can you tell me a bit about the influence of touring with Albert Ayler? And was this clash of opposing cultures between the classical music of your childhood and the world of free jazz that you were exploring as a young musician something that has influenced you for your whole career?

AP: Yeah, of course. That’s an interesting question. I sort of resolved this clash. Leonard Bernstein once played Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question and asked a question: "Where is music going next?" And really I was drawn to the frontier of the movement… to the future. That’s what was exciting me. Classical music had moved into atonality and into electronics and I really wanted to be a part of that. And the next movement into the future was jazz and Albert was the next step in that movement. Albert was the future. Jazz moved from Ornette [Coleman] to Albert. And Ornette was steady rhythms with chord changes that could go anywhere; it wasn’t locked into a harmonic pattern – he called it harmolodics. And then Albert came along and liberated the time so it was totally free. It was very exciting. I was very young and the music was very physical, emotional and passionate and all of those things that a young person relates to. It was just exactly what I wanted to hear at that time. And he freed things up at that time in exactly the same way that Jackson Pollock freed up painting and [John] Cage freed up composition. It was just a place in music where things felt very limitless and was it very exciting. But the audience wasn’t ready for Albert’s music. They hadn’t yet processed Ornette’s music. Albert would say: "I’m breaking reeds here and people are just sitting there. They’re not responding." I just think the timing was wrong for Albert; that was the tragedy for him.

This year marks the 50th birthday of the MOOG synthesizer. How did you come to hear about the instrument because you were a very early adopter of it.

AP: We had a friend, Don Heckman, who was a journalist on the New York Times – in New York the music circles were quite small and everyone knew everyone else. One afternoon Paul said to him, ‘Have you heard anything new or interesting?’ And he played us the Walter Carlos album [Switched On Bach]. I got really excited because it was the first new instrument in 300 years and I was trying to encourage Paul and get some enthusiasm going. I said, ‘We have to get this instrument.’ But he was not that interested because he didn’t have to be. I was the young artist so it was very exciting to me as I hadn’t established myself yet. I didn’t have an allegiance to anything that I needed to abandon to pick up the synthesizer. I was moving ahead a lot faster. Finally Paul agreed to check it out and agreed to go down and visit Moog. He said that if we were to visit him we would have to take a station wagon and bring it back the same day. And that was very clever.

Presumably a prototype MOOG would have been worth a lot of money. How did you persuade him to give you one?

AP: Well, on the drive down I psyched out what would be an argument that would persuade him. And I figured that he would want the MOOG to be used to make serious music and to be seen to be involved in serious music because at the time it wasn’t, it was being used in jingles and in synthesizing Bach and things like that. It wasn’t taken seriously as an instrument. So that’s basically what I told Paul to pitch to him and it worked because he gave us a prototype and we drove it back that evening. It sat in our closet for about six months because we couldn’t find any information on how to use the thing. We went round trying to visit people but no one would give us any information on how to use it, they were all being very secretive. So finally we just rolled up our sleeves and worked out what to do in order to confront it. Originally I thought I would be behind the curtains altering the sound of the MOOG as a composer, conductor like the Wizard Of Oz – because I’m not really an up at the front kind of personality – and Paul would be out front playing. But that didn’t work so then I thought about using it in a non-traditional way, for augmenting non-traditional sound sources like the voice and other instruments. But that was difficult and I had to invent a way to do that.

And this is one of the most notable innovations that you’re associated with. How did you come to this?

AP: Actually someone from a technical magazine in Britain, when I was living there, interviewed me and I described to him how I did it. He said that it couldn’t be done – even though I’d made records of me doing it! That took me by surprise. [laughs] It was just a case of working out how to get in there and control the oscillators and the envelopes and then how to control the sound once you had made contact with it. It was very primitive and rough and I had a lot of problems with the engineers who had never encountered anything like this before – especially in the live situation. At that time synthesizer was generally very difficult to use in the live situation because it was huge and heavy to move around, and not designed for that purpose. And it was unstable. I was never quite sure what sound I was going to get and I was very much flying by the seat of my pants. When we first started performing with it, the audiences had to wait for 20 minutes between songs while I changed the patches from a book of diagrams I’d made. It was very convoluted, but we were pioneering and one has to expect that sort of thing.

Obviously vocal manipulation today is a big thing. Do you have any opinion on Auto-Tune for example?

AP: A lot of that stuff is facile. Obviously there is some creativity involved, as well as a lot of imitation. It’s a trendy thing. A new piece of equipment comes out and everyone uses it because it’s different, but there isn’t a lot of creativity in it and it seems quite finite in its potential. It’s not that interesting to me.

When did you first start recording Revenge and what was your vision for the album?

AP: Well, it was my first record… I’m not sure I had a vision. It was a long time ago. I think I just wanted to be first. I wanted to make my first record and take music into the future. I think I was probably moving really fast because I thought someone was going to do it before me. HA! I had to wait so long before that even began to happen, but when you’re young you have this perception of time moving so much faster than it actually is. But that’s youth, it gives you the confidence that you can actually do it and that you have something to say that people will actually want to hear. All of those kinds of things.

Can you tell me about your own process of free-form songwriting?

AP: That was a lot to do with why I was so interested in electronics and synthesizers. When I came back to New York at the time I started my career – if you can call it that – in the world of avant-garde jazz, everything had broken loose. Everyone was blowing, improvising together simultaneously in the lofts. It was totally free. It was an aggressively masculine texture assaulting you. I’m not male and I wasn’t involved in it so I could see it from an objective perspective. And it seemed like I had to carve space out… to slow things down. So I started writing ballads, with two notes basically, just intervals. No chords. Very minimal. Musicians had no idea what to play on it. Drummers had no idea what to play on it. I felt at the time my responsibility was to create environments that improvising musicians could perpetuate; to create an architecture basically. ECM, the record label, built a very successful label on the concept of those ballads that I wrote. And that’s what attracted me to synthesizers, thinking if I could create the sound, start from initiating the sound at the beginning, creating the rise time and the envelope and the decay time I could slow things down even more. So I was interested in forming a sound that didn’t already exit from the beginning. To create sound itself, and that was very exciting. And that’s how the free form song came about. It was an evolution from Ornette to Albert to the free-form song, which was free harmonically and free rhythmically. It was a new genre.

It was a struggle to get the album out originally wasn’t it?

AP: Oh yeah, they didn’t release it. There was a problem with going over budget. Paul had recorded some music in Boston with his trio but they weren’t interested in releasing it. So they gave me a choice: release the record and the musicians won’t get paid or pay the musicians and the record won’t get released. So I said pay the musicians because that’s the kind of guy I am! But it was devastating. It was agony. It broke my heart.

Can you tell me about the name change for this release?

AP: Yeah, well, it is the third track on the album. And I think it’s a current statement to make even though the record was recorded about 45 years ago. It was a prophetic statement at the time and it is relevant now. You know, I’ve achieved everything I’ve set out to achieve in my life except for two things. One is getting the timing right; getting something out that is appreciated at its time of release because if it’s not I don’t care much about it later on. It has no meaning to me then. And the other thing is being able to release records whenever I like. It takes a lot of money to release records and I have to live very humbly. And that’s OK as long as I have freedom. Sometimes I think that the world awards mediocrity more than it awards originality. That’s a dispute I have with myself though and it’s not based on anything that’s relevant to anyone else though.

Did you see Revenge as a blueprint for I’m The One? Were you taking innovations that you developed for your first album and refining them for the second?

AP: You could say that but it’s more like I’m The One was much more sophisticated and smooth than Revenge. Revenge was young, unabashed, full of abandon. And later I developed more confidence after working with synthesizers for two years. The circumstances were better. I was with a label [RCA]. I had really good studios with really good engineers. I wasn’t making it on the fly. I wasn’t relying on down time and just cobbling together musicians whenever I got the call. That’s how Revenge was made. But I Am The One was produced more and thought about more with a more sophisticated result I think.

I mean this in the most positive sense but on both of these records it sounds like you’re

operating right at the edges of your comfort zone/really pushing at the boundaries of what you feel you might be capable of – is that a fair assessment?

AP: Well, I’m glad it sounds that way, because that’s the way it was. I was a young artist. I didn’t know what my boundaries were. That wasn’t important to me. What was important to me was to be truthful with everything. I was very interested in truth and freedom. Those two things are sacrosanct. A lot of the time you don’t really know what it is that you’re doing. You’re not really aware. And that doesn’t really matter. If you can just get the statement true; if you can get it to sound and feel the way you intended then that’s success. That’s all you need, you don’t need to question it. You just need to manifest what you hear or feel.

I don’t think of myself as a singer; I’m a composer. So I compose a piece of music and then I figure out a way of singing it. The way I do it is to just go for it. I feel the music and I just go for it and that’s maybe why it comes out like it does. But it’s honest and not pre-conceived. The performance part of it is not invented in anyway. I’ve reached the stage now where I feel like the pieces deserve a better performance. In the beginning I wanted someone else to perform them and not me but I couldn’t think of anyone else who I could depend upon to do them so I did them myself. But now I’ve been working with my voice and recording a new release – it’s long overdue. But because I feel the pieces deserve a better performance so I have been working on training my voice. Not with anyone else but by myself on the pieces, working out the best way to sing them so that they get the performance that they deserve.

Can you tell us a bit about this new album – because that’s very exciting news.

AP: Well, I’m hoping that it won’t be a posthumous success because I don’t have another 20 – 40 years left for it to hit with the public! But I’m hoping that I get the timing right on this. That’s what I’m aiming for. I’m hoping that what I produce, for once, is going to be right for the marketplace.

I Belong To A World That’s Destroying Itself is out now on Ironic