Annea Lockwood portrait by Sam Green

‘For Ruth’ and ‘Conversations ’74’ plus A Film About Listening make up part of the bill for this year’s Counterflows At Home digital festival which runs for all of April

“Tell me everything…”

“What is everything? That we love each other?”

“Yes, yes, yes… love!”

This begins with a love story. New Zealand-born composer Annea Lockwood’s most recent composition ‘For Ruth’ is a reply to a love letter on tape her late partner Ruth Anderson made her in 1974, titled ‘Conversations ‘74’. In ‘For Ruth’, their affectionate conversational fragments, loving affirmations and the bubbling laughter of two people giddy for one another are embraced by field recordings of rich birdsong, grumbling frogs and passing cars, as well as resonant vocal intonations, which sound like the tintinnabulation of struck metal. The few complete sentences that surface contain an exchange that is a sort of found poetry on the feeling that the world has become whole through partnership with another person.

Lockwood met Anderson in 1973, when she was hired as cover at the electronic music studio Anderson ran at Hunter College in New York City (one of an estimated three women in the US at that time to have designed and run her own studio). Anderson had asked Pauline Oliveros to fill in, but Oliveros was also on sabbatical at the time, and had suggested her friend (the then) Anna Lockwood, who was living in the UK. “Ruth called me up one evening, got me out of the bathtub, and offered me a job in the US,” she tells me brightly over video call. “Of course, I jumped at it. I’d been dying to get over to the US. So I went to New York, met Ruth, then a week later she invited me and my then partner Harvey Matusow to visit her in New Hampshire. Ruth and I just fell in love in those three days. She was wonderful, a lightsome personality, wise and kind, and most generous, so of course, I fell in love with her right off the bat.”

After that, they started calling each other regularly, and Anderson began taping their conversations, which she spliced into a gift – a jocular love letter – to Lockwood. ‘Conversations ‘74’ is a quick-cut collage of mostly non-verbal parts of their exchanges – sneezing, sighing, greeting, questioning, giggling – intercut with some lolloping detuned barroom piano tunes, sloppy with delay, or perhaps drunk on love. “We said, ‘Oh, we can listen to this together when we’re old’, but we never did,” Lockwood says.

Ruth Anderson died in November 2019, before the release of Here, her first full length album (on the label I run, Arc Light Editions). Lockwood found the tape Anderson had gifted her while going through her shelves, and asked mastering engineer, composer and musician Maggie Payne to make a digital transfer. Both pieces – ‘Conversations ‘74’ and ‘For Ruth’ will be broadcast in April as part of Counterflows At Home, along with a film about Lockwood by director Sam Green.

“The two pieces are bookends to Ruth’s and my long marriage,” Lockwood tells me. She agrees that ‘For Ruth’ is perhaps the first love song she has composed across over her long career. She describes her work as being about the transfer of energy and has also made music with glass; documented rivers from source to mouth; burned, submerged and buried pianos; permanently prepared them with plastic lips and bubble machines; incorporated poetry by Etel Adnan and Guantánamo detainees, and composed for choir, trumpet, gongs, didgeridoos and other instruments. She will be 82 on her next birthday, but is as animated and excited as a teenager when talking about the way sound operates in our environments and upon our bodies. Over the course of our chat, she frequently breaks into huge smiles that are like the sun coming out. “I’m really interested in the way sounds unfold – really interested!” she says, grinning. “Whether that’s sounds from the environment – a frog talking to a frog, or [trumpeter] Nate Wooley, at the end of our piece ‘Becoming Air’, raising his trumpet bell up to the ceiling to put his throat into a strange position, but keeping the note going. I feel that sounds are autonomous – they have a sort of life span… That’s at the bottom of a lot of my work. It’s in the pacing of my work, and it’s in how I layer sounds… or don’t!”

Lockwood approaches sounds with open arms, she is curious about their operations and pays them acute attention, and while she’s a known figure in avant garde circles, the last decade has brought more widespread attention to her work, which has new resonances in a time of climate crisis. There have been residencies at Café Oto and LCMF, a Composer Portrait concert at Columbia University’s Miller Theatre, a large New York Times feature, reissues of her work on Oren Ambarchi’s Black Truffle label, and performances of her work around the world, as well as behind-the-scenes research by individuals such as Louise Gray which has filled in her history.

Annea (originally Anna) Lockwood was born in the summer of 1939 in Christchurch, New Zealand. She studied piano and composition, and moved to London in 1961 to continue studying. Her route out of New Zealand was either to the US or UK, she says, and since her mother was from Southampton she headed to the Royal College of Music and attended various summer schools. She studied electronic music, but wasn’t satisfied: “It was fun to put sounds together with massing oscillators, and filters and ring modulators and whatnot,” she says, “but the sounds we were making weren’t intrinsically interesting to me… So rather than make myself figure out ways to do just that – which of course with granular synthesis and so on, has been beautifully done – I switched to another domain of sound.”

Lockwood began thinking about how to present audiences with a single sound, asking them to “treat it as a miniature composition, and hear how complex and interesting its internal structure could be”. She wanted a material with which people didn’t have instant associations: “If you couldn’t identify a sound, it would hook you in,” she reasoned, and came up with the idea of glass. The glass concerts were Lockwood’s first, formative sound works in which she worked with nothing but glass. They were part art installation, part composition – early performances took place at a London venue called Middle Earth. They were resonant, crystalline, and shattering, made with goblets, glasses, bulbs, rods, micro glass for scientific uses, a bottle tree, and great panes suspended in the performance space. To stage these shows she got in touch with the glass manufacturers Pilkington. “I wanted see not only the finished products, but the debris, and the processes,” she explains. “I made several trips back and forth to their various factories, and they would just let me take whatever I wanted, and would find stuff for me that I might be interested in. I did a number of glass concerts and travelled with it by boat at one point, and they made these beautiful wooden cases for the big glass panes and the glass rods to travel in. They were so good – Pilkington were big enablers!”

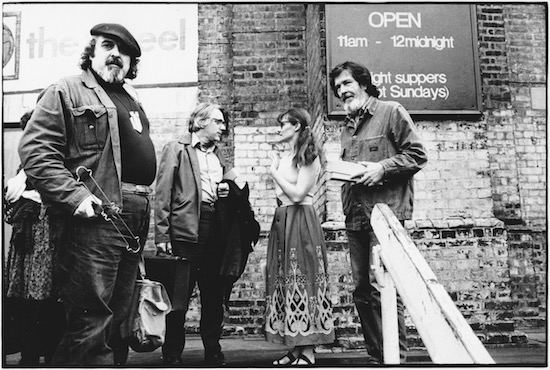

Harvey Matusow, David Tudor & John Cage with Annea Lockwood, photographer unknown

The 1970 album of these works was made over the course of two years, mostly at night in the basement of a church in North London, after she was invited to make a record by Mike Steyn, who ran a label called Tangent that released anything from Ethiopian music to Scottish stand-up. Today, the glass concerts might be regarded as novelty by anyone who hasn’t listened to them in full, but Lockwood says this wasn’t an issue at all: “I was working in a world in the late 60s in which, in all the art forms, really, we took for granted that we could work with any material in any way we could imagine,” she tells me. Around this time she was also improvising in a group called Naked Software (with Hugh Davies, John Lifton and Harvey Matusow) who once used a map of Everest as their score, and made ‘sound hats’ for Henri Chopin’s poetry magazine Revue OU, where the movements of small objects such as bamboo and table tennis balls hung off the hat and created a personal tinkling soundtrack for the wearer. However, she says the glass works were “really the soil out of which absolutely, everything else has come”. Soil is perhaps an appropriate metaphor for some of the works that came after, namely, her ‘Piano Garden’.

‘Piano Garden’ was one of her Piano Transplants, the first of which was a permanently prepared piano made in 1967. “I’d been playing some of Cage’s prepared piano pieces,” she says. “I had an old upright and remember thinking about how Cage always had to take those preparations out of the piano, dismantle them after every performance, so I started imagining what you could do with a piano – what you could put inside it, attach to it, resonate from it – if you were not worried about preserving perfect tunings. And I like playing, and I like absurdities, so I started concocting all sorts of possibilities to permanently prepare a piano.”

With help from her friend the artist John Lifton, the piano was given a large set of plasticine lips and a mouth, which would spurt bubbles when the soft pedal was depressed. She was also good friends with composer and instrument-maker Hugh Davies at the time, and they would often go to a store that stocked parts for toy dolls. “At one point they had little eyeballs with eyelashes and eyelids,” she says. “So, the piano has a couple of eyeballs with eyelashes which flirt with you if you trill on two particular notes. There were all sorts of things which would bounce against the strings and resonate them. I remember inserting some slivers of bamboo into tiny little holes in the soundboard so that you could play it like an mbira.”

The second piano transplant was ‘Piano Burning’ in 1968, prompted by a practical impetus not a destructive one – Lockwood needed to record the sound of fire for another project, and bonfires, hearth fires and other attempts had failed to produce any interesting sound on tape. She knew there was a place in London where she would find discarded pianos, and Bob Cobbing had asked her if she’d like to do something for a festival he was putting on along Chelsea embankment. She suggested a piano burning. “I always want to get as close as possible,” she says. “I wanted to put a microphone right inside the piano, inside the fire, for as long as it would last. So, we wrapped a couple of mics and cables in asbestos, and set up a little tape recorder, and started the piano burning. As a recording, it was totally useless – people just were magnetised, they glommed onto it and talked their heads off! But what was astonishing was how beautiful and strange it was as a visual spectacle. We did another one that night – had always planned to do two – and at night, it was exquisite. In relative darkness, it was just gorgeous. So, it became this curious hybrid: a visual, conceptual, audio event.”

Annea Lockwood and ‘Piano Burning’ by Geoff Adams

The score for ‘Piano Burning’ instructs to “play whatever pleases you for as long as you can,” the last one was made by LA hip hop trio Clipping, and is the final track on their 2019 album There Existed An Addiction To Blood.

The next was ‘Piano Garden’ in Ingatestone, Essex, where Lockwood was living at the time (a ‘Piano Garden’ was also ‘planted’ in Llanrwst, Wales in 2013). “It was about me wanting to watch the contrast between the delicacy of young plants pushing up and working their way into the heavy, strong construction of something like a piano, pulling the piano slowly apart,” she explains. “I love the contrast between delicacy and the tremendous strength of plant energy. I wanted to watch that happen. But then there’s always playfulness involved, so one of them was sunk at the right angle for the Titanic going down, and a little grand piano was set up near the gate, and as we were on the lane from the station, people would wander in when they got off the train and play a few notes.”

She also sunk a piano in a cattle pond in Texas for ‘Piano Drowning’, and then there was ‘Southern Exposure’, where a grand piano was beached (a composition renamed according to where the beach faces). When this was realised in Perth, a grand piano was set on a beach at high tide, with a sea anchor and then “you wait for the water to decide what to do with it,” says Lockwood. A composer called Ross Bolleter had dug them out the discarded grand, which was carted down to the beach, given a sea anchor, and people played it. “We went away and had dinner and celebrated,” she says, “and the next day the piano disappeared. A bunch of backpackers had been walking along the beach, come across the piano and decided to rescue it. So they picked up the piano, carried it back to their hostel, stuck it under the TV and set about restoring with it linseed oil.”

In the meantime, alerts had gone out to the coastguard and harbour, presumably about an escaped grand piano that may pose a danger to shipping. It was soon returned to the beach, and gradually the piano lost its legs and had its body filled with sand by the tides. Later, when it was no longer playable, it was retired to a glade of eucalyptus and gum trees, where it still resides.

We are both laughing as she recounts this story of someone nicking off with her installation, and as we regain our composure I am struck by Lockwood’s pleasure in sound, by the playfulness and exploratory feel to much of her work. She has no preciousness about how work should be interacted with, but it is her generosity as a composer that means her enjoyment can be shared by the audience.

Pauline Oliveros, Annea Lockwood and Ruth Anderson photographer unknown

This is also evident in her visible excitement when we discuss a current series of events at Issue Project Room in New York, in which a group of musicians and artists have responded to Women’s Work, a magazine of scores Lockwood published with artist Alison Knowles in the 70s. It included unconventional scores and contributions from artists such as Christina Kubisch, Mary Lucier, Pauline Oliveros, Carolee Schneemann and others, and was intended not as an archive, but as something to pick up and do. Lockwood says the prompt was wanting to push back against the fact that “work by women artists was not being made room for as it should have been: it was not as not prominent as it needed to be; was not on an equal footing”. They assembled Women’s Work with women artists they knew and whose work they cherished, “with a view to asserting: this is what women do, this is women’s work,” she says. It was republished a few years ago by Primary Information, a beautiful object and a crucial text within avant garde composition.

Perhaps Lockwood’s largest scale works are her river pieces, which began in the 80s, when she needed a job and asked at the Hudson River Museum if they needed anyone in admin. The person in charge took one look at her, spotted she was an artist, and invited her to make a proposal instead. “I looked out the window at the Hudson and thought, why don’t I do an entire river? I’d been in New York long enough to know how much New Yorkers love the Hudson, but that it’s often visual. I thought people didn’t really know the power of the river, but if you can hear a river, you can hear its energy.”

Prior to this she had begun building what she called the river archive, her own recordings of rivers and streams, plus those friends brought back with them from their travels to places including the Himalayas and Massachusetts. “I’ve loved rivers all my life, I grew up with wild rivers,” she says. “I’d become interested in why we’re so drawn to them. I already knew or had a feeling I wanted to work with them because their textures are so complex, and constantly shifting. They stimulate the mind on at least a couple of levels, and I wanted to explore that – is the sound of moving water particularly nourishing? My suspicion is it is.”

Her fascination with water and rivers is what led to her adding the extra ‘e’ to Annea some time in the mid-1970s (pronounced as if the ‘e’ were ‘é’). “I had been back to New Zealand to visit my mother, and while there I heard that in Maori traditions there was a female embodiment of the Pacific ocean, Ea. I love that ocean, its vastness and its rhythms,” and says she regretted a lack of connection to her country’s indigenous population, “so I changed my name to evoke her. I couldn’t swear to the accuracy of my memory, or to whether such a tradition exists; people to whom I’ve mentioned it tend to look puzzled.”

Since A Sound Map Of The Hudson River, Lockwood has also made long-form recordings of the Danube and of the Housatonic. Both are also installations, the latter has a map and clock timer, so you can trace your route as a listener down the river. To sit and experience one from start to finish is to be struck by the breadth and complexity of the sounds of water. She does not idealise these environments, and neither are they just documentations – she composes with the sounds in a way perhaps comparable to a documentary photographer composing a photo. They contain political elements – particularly in the Danube, which she recorded between 2001-2004 – but can also be humorous. At one point in the Danube recordings, there is an intentional and hilarious quick cut to a particularly vocal flock of sheep.

Since the late 80s, Lockwood has written more regularly for instruments than objects – although she might not appreciate the distinction, being more concerned with sound as a transfer of energy than their categories. There are often tape works within her compositions, and she tends to work collaboratively, such as with baritone Thomas Buckner. Prepared piano piece ‘Ear-Walking Woman’ was made with Lois Svard; ‘Thousand Year Dreaming’ with a collection of musicians exploring the acoustic interplay between instruments including conch shells and didgeridoos; ‘Becoming Air’ is a more recent collaboration with trumpeter Nate Wooley; ‘Into The Vanishing Point’ was composed with the quartet Yarn/Wire. If this sounds like a turn towards more conventional composing, it’s not. ‘Jitterbug’, from 2007, uses photographs of rocks as graphic scores, the images shot by Gwen Deely and the rocks pulled by Lockwood from a creek bed in the Montana Rockies. Musicians play against a fizzing backdrop of aquatic insects. In ‘Gone!’ a miniature music box piano is tied with helium balloons to float upwards above the audience, playing its tinkling music. ‘Water and Memory’ is for 12 or more non-professional musicians, and was commissioned by the Holon Scratch Orchestra women’s choir in Israel. It incorporates group humming and the Hindi, Thai and Hebrew words for water. Having performed this piece, I know that the humming creates a buzz, activating the mind and body through the bones in your skull, and inducing a sort of physical high. At the close of the piece, the audience are invited to hum too, gifted the same high as the performers.

“I’ve been interested all along about how sounds affect our bodies, because of course they do,” says Lockwood. “Pauline [Oliveros] was simultaneously interested in that – it was one of the things which got us corresponding in the late 60s/early 70s. You move from awareness of – and preoccupation with – how sounds affect our bodies, into how that might create a web of connection with the external world – with the natural world.”

One example of work that triggers a physical response is ‘Tiger Balm’, a tape work from 1970 using sounds such as a purring cat, a slowed down jaw harp, a tiger, a woman’s breath, a plane passing overhead – all sounds she felt were erotic. It was also a creative shift, from what she thought of as the ‘ear training’ of the glass concerts, to composing with multiple sound sources. “I needed to figure out a way to construct that flow” she says. “I thought, what if I tried to dream it? At night before I went to sleep, I would give myself the dream task of dreaming up what would happen next in ‘Tiger Balm’, of how the sounds were combined. Then when I woke up, I scribbled down any ideas that came to me.”

The ecological aspects of her work she says have become more explicit in recent years, and more present to her as a composer. “Where I am now is that I feel that sounds affect our bodies so strongly. We’re not necessarily aware of the entire range of those effects, but they’re there: our bodies are responding,” she says. “That’s a connection to the source of the sound. If you can focus on how you feel in response to hearing something from the environment, and then become aware that you feel connected to it, you can move into a state where you don’t feel separated from that phenomenon. That strikes me as the actual reality – that we are not in any way separate, however much we’ve been trained to think of ourselves that way.”

This knowledge does not just come from Lockwood’s explicitly environmental compositions. When it is broadcast, ‘For Ruth’ represents not just a reply (and a farewell) from Lockwood to Anderson, but also offers a web of connectedness, a piece in which the “huge mutual recognition” she said she felt the moment her and Ruth met, unfurls as a recognition of the connectivity between all of us and the world around us too, in loving sighs and affirmations, singing birds and sung tones, and even the grumbling frogs of New Hampshire. “I don’t have plans for new work. That could be because making ‘For Ruth’ was an act of completion in many respects, including in relation to my work,” she says. “I owe her so much. She transformed my life.”

‘For Ruth’ and ‘Conversations ’74’ plus A Film About Listening make up part of the bill for this year’s Counterflows At Home digital festival which runs for all of April