“No other art has such an intense mode of expression with such an abstract language.” Intensity is inherent to Anna Zaradny’s work. Intensity that builds over time, embracing more and more layers of details, weaving an ornamental sonic structure that is logically precise while aesthetically elaborate. The listener is engulfed by masses of sound, a rhythmic pattern emerges.

Zaradny has been involved in the various facets of music having undergone classical music education, and graduating in conducting and music theory. She later embraced jazz and various noise and punk alternative subcultures. An openness to contingency as found in improvisation and underground music, but with a confidence and awareness of someone in control of what they are doing defines her.

Zaradny’s music is not coincidental. Besides music, she’s an accomplished visual artist, working at the thresholds of sound, image, light, space. The artwork, both sonic and visual, is a result of the creative mediation between the idea and its interpretation and realisation which oscillates between ethereality and urgency. She founded the festival and label Musica Genera alongside Robert Piotrowicz in 2001. The imprint has released the likes of Zbigniew Karkowski, Otomo Yoshihide, Burkhard Stangl, Robert Piotrowicz, erikM and Zaradny herself. Her second, critically-acclaimed album Go Go Theurgy was released last year on Musica Genera. She’s currently working on her new album and preparing for the 5th Biennale de Lubumbashi RD Congo.

What does the term experimental music mean to you personally?

Anna Zaradny: I think the word ‘experimental’ is used in the context of the need to distinguish something from the common and the typical. It has lost its meaning. It is only an adjective, a label which barely expresses anything. On the other hand, there is no other word that would more precisely describe [my] many musical practices, attitudes and creative approaches. I define experimental music through the prism of my own experience, the clashing with certain artists and genres I have encountered so far. Looking back at my own path, working with free improvisation, noise music, experimental electronics, collaborating with other artists (Burkhard Stangl, Christian Fennesz, Tony Buck, Maja Ratkje, Jerome Noetinger, Otomo Yoshihide, Zbigniew Karkowski, Robert Piotrowicz), I have a very certain view of it and I think it relates to sense.

Can you elaborate – in what way or how does it relate to sense?

AZ: I mean the essential change to the perception of the process of creating and performing music, defining one’s own instruments, moving the boundaries of the very basic sense of what music is as a medium. Those artists embody an uncompromising approach to all those aspects, sometimes trying to destroy everything that used to be considered as music, sometimes choosing parallel paths.

One of the most important aspects of experimentation is to create one’s own language and to explore through new means of expression, technique, sound, context etc. Not every time that means that artists discover something new, or that the way they create their art is based on experimentation. I think it is also a very personal experience of breaking through your own limitations and moving to a point where you have never been before.

Can you talk about your background – your path to music and the subsequent ‘rupture’ with the classical music world?

AZ: My musical path has been multidimensional, both as a recipient and as an evolving artist. I went through all the stages of music education: from primary school to music academy. In parallel to classical training for violin, piano, saxophone, opera singing and conducting, I also played in jazz big bands and I was quite active in the alternative scenes and subcultures, I played in a well-known Polish punk band, for example. All of that was very influential. A major change in my perception of music occurred when I joined the noise hardcore band Stuck On Ceiling (I played second bass guitar, later saxophone). This group inspired me a lot by their uncompromising way of working with music and attitude. The band was progressive, experimental and radical. Gradually it transformed into a purely instrumental, improvisational ensemble, and it became an entrance to what I have been doing for years so far.

My early concert experiences of free improv and experimental electronic music mostly came from the scene’s traditions in Berlin, Vienna, London and France. Around the same time, together with Robert Piotrowicz, we founded a festival of improvised and experimental music. Musica Genera has been operating as record label as well, which was a natural extension of our festival activities. Over the years, I focused on free improv and as a saxophonist I played in different constellations often with Burkhard Stangl, Robert Piotrowicz and Tony Buck. I began to use the computer as my instrument at concerts and as a composition tool. I focused on my author music, it became one of my main artistic activities and it is very important for my present work as well. My work expanded into other fields, and for a number of years I also composed music for theatre performances and bands. I also started to work in sound and visual art. Nowadays, strictly musical projects penetrate and interact with visual ones, complementing each other, or even becoming a synthesis of it all.

What fascinates you about sound in particular?

AZ: I think first and foremost it is the incredible power of sound that affects on the psycho-physical and emotional level. No other art has such an intense mode of expression with such an abstract language. It influences and penetrates all senses being only vibration of air. It is fascinating how music and sound work with time and space. It happens both in electronic and very synthetic sounds as well as sounds of acoustic instrumental and natural origin. Sound as a phenomenon is absolutely mesmerizing. I’m interested in multi-layered sound, a wide band of dimension where it resonates as well as the contextualization of sound, for example its absence, removal on purpose etc.

Once you mentioned that in Poland, there’s a lack of references in the avant-garde musical tradition. Do you feel it affected your generation of musicians (as well as the subsequent ones) in Poland, and if so, how?

AZ: I meant a breakdown of a certain avant-garde continuity. It happened everywhere in the world, I guess. We have a very long tradition of contemporary music and jazz. I had a feeling that in this period of the 90s – 2000s, the avant-garde Polish tradition of the 1960-70′ wasn’t such an inspiration for the new music coming from Poland. I experienced this continuity in a much wider scale in the West. I think it is different today though. There are a lot more musicians and artists who work in that tradition in jazz, electronic music or contemporary classical. There have been also many archival publications in the last years, and this has certainly changed the knowledge and attention around these aesthetics.

One review of your Go Go Theurgy record mentioned ‘feminine pressure’ in connection with the album. Your work Octopus, for instance, has images of the female body. You have also reinterpreted the work of Hildegard of Bingen. Do you take into consideration the female/ feminine/ feminist aspect in your work?

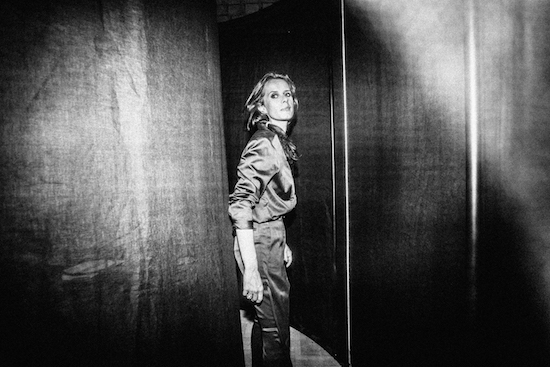

AZ: At some point I decided to use my own image on my record covers. The reason was artistic. This kind of music usually uses abstract, geometrical imagery on the covers. I wanted to do it differently and it was in a way an act of exhibitionism to comment on abstract music with sensual and personal colours. It always revolves around a specific idea, story or a concept. I try to build a narration with the title of an album or through hidden themes and liner notes. That’s somehow the sense of the tangible feminine presence, the emphasis on physicality, taking part in the tropes of pop culture with its focus on image. I am a woman, the artistic and social experience that I’m acquiring on the basis of sex is naturally present in my work. I am working around female themes – sometimes stories of female artists – to correlate with some kind of male domination in music and art in general.

I reach for it naturally, often in ambiguous or non-direct ways. Sometimes I create common narratives and dialogues between these clues and my work. Hildegard of Bingen is my feminist progenitor, an outstanding composer and a very strong and charismatic woman. I dedicated one of my sound installation to her. This is an object, a prototype of an instrument, it has many meditational, metaphysical, compositional, and constructor connotations.

In that context I also made two videos. The first one for Octopus was released on the split LP with Burkhard Stangl, and the second was made for the composition from my last Go Go Theurgy album. These are short film forms made for a musical piece. I wanted to play around with the clichés of music videos intrinsic to popular music. I used experimental or abstract music – however you name it – to change the context but also to mark the common area for working with sound and motion image. These pieces refer to different aspects, such as the free relationship with the traditional form of the music video, the presence of the artist in his or hers own work, and the organisation of the visual structure coming from abstract music composition.

Go Go Theurgy‘s visuals have ritualistic, witchy connotations. There’s an aspect of magic and hypnotism to your music. Can you talk about the ritualistic aspect of your work?

AZ: I wanted to express some kind of ritual I have achieved in the structure of music. Go Go Theurgy is another of my compositions where the density of the sound layers and repetitions of sound events play a very important role. This album exploits the idea in a large scale. With the visual side of the piece I wanted to extend the field of expressions to an exact ritual oscillating between dance, performance, concept of defiance and power. In my other works I often relate to a ritual stripped off its mystical aura. I’m interested in expanding the tension between cultural roles and their phantasms as well as performative aspects of space in a direct and metaphorical way. Ritual as an act is a very rich experience inviting enough just by being pure. So in my case it is not a shamanistic practice to summon the divine or supernatural to visit the human world. I wanted my Theurgy to be related to the existential sense also including cleansing which profits from experiencing music of that nature. An intense and intimate performance of gesture or space being very private sensation which at the same are common and to be shared.

AnnaZaradny • Theurgy Two • Teaser from KasiaMichalskiGallery on Vimeo.

You haven’t released many records, Go Go Theurgy was your second solo release so far. Why is that?

AZ: That’s right. I’ve released seven records partly in collaboration with – among others – Tony Buck, Burkhard Stangl, Christian Fennesz, Robert Piotrowicz, Kasper Toeplitz, and just two solo albums. Why so few? First of all, for many of years, I focused on playing concerts and contributing to the organisation of the festival and the record label. I was doing recordings at that time, but not always decided to publish them. Despite the recording sessions and music that could have been released more often, I decided to keep it unreleased.

I think that it is worth to release music whose value can survive over time. Regardless of how banal it may sound, it is quite difficult to judge and make decisions. I try to be careful on that matter. Making a piece of work public is essential for an artist, but I wish to make it also valuable for the listener. It is easy to succumb to the profound subjectivity of these two poles. I hope I manage to keep the ratio. Maybe I could get at least one more record out. [laughs]

I was also developing my visual and sound art activities, so a big part of my focus shifted from music to working with sound in space, objects and videos. Sometimes I also had this strong impression of overproduction in art and music. Maybe that is why publishing everything that is composed or recorded does not make sense to me. I think it is important to get a distance from one’s own art and need of publishing. Of course, I speak with all my respect for artists who might think otherwise.

You have been also involved in organising: Musica Genera in particular, which is a now-defunct festival and an existing label. The period around 2005-10 seemed to be particularly active for the scene around the initiative. What are your memories of it?

AZ: Musica Genera Festival was a project established by Robert Piotrowicz and me. We built it from scratch. Music and sound materialised not only as concerts or recordings, but also in the form of real object and ideas. We treated it as [pertaining to] equal works of art. That emancipation has great importance to me – developing an idea which was directed at spreading the meaning of sound, negotiating its place in culture and the arts. Musica Genera was held in various cities and locations, sometimes different countries. We tried to have no geographical limits. The annual three-day happening in Szczecin was at its core, which acted as a blueprint for all the other events that were emerging in different contexts. The festival brought me a lot of experience. Meeting so many artists, bringing their work to audiences and creating a platform for something new. Putting a spotlight on that kind of music and art was an incredible sensation. We usually invited artists to create new works, either on stage or via site-specific pieces and performances. An important part of the project was to diminish the distance between the artist and the audience. The participation of the listener was extended with post-festival commentary, the active sharing of views and experiences. It was truly unexpected and great. Musica Genera now only exists in the shape of a record label, mostly releasing vinyl in the last few years.

Can you elaborate on this idea of emancipation?

AZ: We didn’t relate to this institutional or post-institutional narration that happens today, and haven’t been a social movement in that way. We were inspired by the idea to make abstract or ‘experimental’ music part of everyday culture, as theatre, visual arts or films. That was emancipation because this aesthetic is excluded from high culture and described as ‘difficult’, ‘obscure’, not of social or economic use.

Anna Zaradny is a participating artist of the SHAPE platform for innovative music and audiovisual art, supported by the "Creative Europe" programme of the European Union