It takes a special kind of zero-fucks bravado to walk onstage wearing see-through plastic trousers. Andre Cymone, never a man lacking in self-confidence, did exactly that, every night between 1978-1981 as a member of Prince’s backing band. And he wasn’t just obeying orders from the boss: the eye-poppingly outrageous stage gear was his own idea.

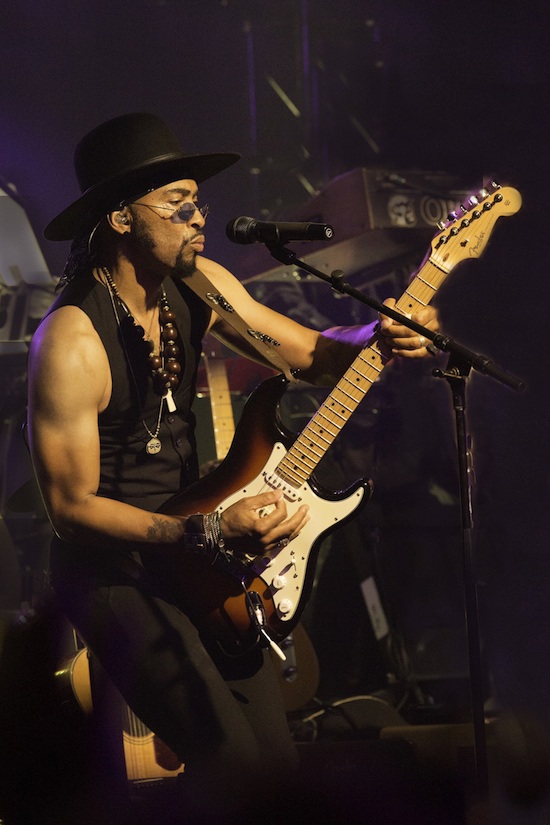

It’s a relief, then, to find that nowadays he favours a more modest pair of dark blue jeans, at least for interview purposes, but the rest of his attire – denim biker jacket, psychedelic floral shirt, bandana, big round sunglasses, goatee, neckerchief, hippy hat – is the very apex of funkateer boho chic. His new album, 1969, is a Sly & The Family Stone-esque rock/funk romp bearing a recurring message about the racial strife of Trump’s America. Cymone, however, doesn’t look old enough to remember that year: he could easily knock 15 years off his age of 59 without anyone raising an eyebrow.

Born Andre Simon Anderson in Minneapolis in 1958, Cymone grew up alongside Prince. Not just as his bassist, but his best friend, his housemate, and near enough his brother. From their first band Grand Central through Prince’s early years as a major star, the pair were inseparable. Cymone’s bass style, combining the elasticity of funk with the edge of New Wave, was integral to what became known as ‘the Minneapolis sound’. Furthermore, as he will tell me, he was the uncredited co-writer on some of Prince’s most famous songs.

In 1981, midway between the Dirty Mind and Controversy albums, Cymone amicably quit the Prince camp to launch a solo career, beginning with 1982’s Livin’ In The New Wave. After three albums, he concentrated on production, working with artists including Adam Ant, Tom Jones, Jermaine Stewart, Lipps Inc, Evelyn ‘Champagne’ King, Tiffany and Jody Watley.

However, his connections to Prince-world have, if anything, become even stronger since the singer’s death, and Cymone has performed live with two of Prince’s former backing bands, The Revolution and The NPG. Some former collaborators can turn suddenly frosty when the topic of Prince arises. Not Andre Cymone. He brings it up himself. We begin by discussing 1969, but it isn’t long before we switch to the subject of the late genius. And stay there.

Your current album is called 1969. Is that because you see strong similarities between then and now?

Andre Cymone: That’s absolutely the case. A couple of things about 1969: for one, the parallels. You’ve got the insane police brutality, then and now…

So you’re comparing that brutality to the police treatment of the Civil Rights movement, the Kent State massacre, anti-Vietnam protests and so on?

AC: Exactly. There are so many parallels. You almost can’t make this stuff up. A little bit ago, a kid was riding his bike without a helmet, and he was afraid because the police saw him and they were coming after him. And he goes home, and six police officers show up outside his house, and they want to arrest him because he wasn’t wearing a helmet. His mom calls down to them and they say they need to arrest him, and eventually she sends him down, and of course they beat him up. And it was just about a helmet. And as an artist, if you have any integrity, you’ve got to start writing about this stuff and speaking out.

On the album, there’s a track called ‘Black Lives Matter’, in which you cleverly reclaim the counter-slogan ‘All Lives Matter’, which has become a racist dogwhistle…

AC: Yeah, and I got a lot of flak about that. The reality is that all lives do matter, and people shouldn’t section themselves off and say ‘I only represent this’. That isn’t what life should be about: "They’re over there and we’re over here." We need to realise it’ll never work like that, with that mentality.

It’s almost too obvious a question to ask, but why is Black Lives Matter the most important issue for you right now?

AC: A couple of things. For one, where I grew up, we had a huge riot in my neighbourhood, which burned down the whole area. I’m talking about the 60s, probably ’68. And it was because of the same thing. And I remember, all the grocery stores we used to go to, burned down because of the same thing that’s going on now.

And even as a child, you understood what it all meant?

AC: Absolutely. My family was very politically-minded, my mother was very involved in the community. So it was natural for me to think like that, and to be involved. There were freedom marches, and throughout the years I’ve always gone on things like that. It’s nothing new. It’s not as if I’ve just decided now. I’ve always been part of the political environment in my own state and my own town. I’ve gone on marches, and if people are campaigning and I can lend my voice, I have. I’ve helped Keith Ellison [Democrat representative from Minnesota]. I played ‘The Times They Are A-Changin” for him in Atlanta when he was trying to become head of the DNC. I’ve always been involved.

The Black Lives Matter movement grew as a response to a number of news stories about young black men, often unarmed, being killed by police. At what point, for you, did this stop looking like a sequence of isolated occurrences and freak coincidences, and start looking as though something was going on?

AC: First of all, from my perspective, that point was reached a long long time ago. In the black community, it’s always been going on. It’s just that now, obviously, we have social media, and everybody has a cellphone. It’s happened to me, it’s happened to my brothers: both of my brothers have spent time in prison. And within the black community, it just is what it is. But now, you see it on a constant basis, so it’s become a topic of conversation. And people are gonna have to address it. No matter what side you fall on, there’s no weird spaceship that’s gonna suck all the bad people out and take them away. It’s not gonna happen. What’s got to happen is people like me, or people like you, journalists, write about it. And again, going back to 1969, it took everybody. It took journalists, artists, poets, musicians of every stripe, from Joni Mitchell to Joan Baez to Bob Dylan to Curtis Mayfield to James Brown, then all the different writers to get behind that movement of peace, love and happiness, and to understand that we, as artists, can move things in a positive direction. Because that’s what happened then. If you think about the Vietnam movement, and Flower Power, and the photographers who captured those pictures, and artists like Peter Max, it was all-hands-on-deck to say "You know what? I want our world to be about freedom. To represent me and you, to do whatever we want and dress however we want, play how we want, live how we want." There’s still people who don’t want that to be the case, and do whatever they can to divide and conquer, and create little sections and all that bullshit. But it’s up to us. We have to stand for something. And like they say, it’s an adage that you get 60, 70, 80 years for your lifespan, and this is our time. And what are we gonna do with it? Are we gonna just sit on the sidelines and let someone else run it in a way we hate? No!

It’s interesting that you use the word ‘stand’, in the context of 1969 and what was going on, because on your album’s opening track, I hear a bit of Sly & The Family Stone, who released an album that year called Stand!, espousing a lot of the same values…

AC: Absolutely! The first track on my album is ‘We All Need Somethin”. That song says: "Put it plainly, I’ve been freaking bored since I was cut from my umbilical cord…" And that’s the truth. I always used to thank my parents: "I’m just glad to be here, and if you did nothing else for me, I’m just glad to be here. I’m breathing, and I can do whatever I want. It’s up to me now. Thanks!" And I’ve made money, and bought my mom a house and my dad a car and all that kind of stuff, luckily, but it’s not even about that. It’s that they got me here. And then it’s up to you. You’ve got that gift of life, and you’ve got to find out what your gift is. Everybody’s here for a reason.

On the song ‘Black Man In America’, you use the 60s radical slogan "No Justice, No Peace", revived recently by Black Lives Matter. Is that how strongly you feel?

AC: Oh, absolutely. That song, ‘Black Man In America’, is even more pointed. You have to stand up. You can use all the adages like "the squeaky wheel gets the oil", and I don’t see enough of it happening.

Do you think music’s response to racist violence has not been strong enough?

AC: Not even close. You have a handful of artists kinda sorta speaking out, and it became kind of trendy for a minute. It wasn’t even committed. You might know more than I do, because I don’t get so involved in what everyone else is doing, but I just know what I saw. And that’s the reason I started doing it, because no-one was speaking up. A couple of high-profile people spoke up, and suddenly it’s "Oh, it’s trendy, let’s all speak up", but then it goes again. And it has to be a commitment. You can’t think about your reputation or your career. You’ve got to think about the future of your grandkids. It’s evolution. It’s not about me or any individual. There’s a bigger picture. A lot of people want to have the big fancy car or the big fancy house, but what good is it if you can’t park it somewhere and you have to worry about someone breaking in? I wasn’t raised that way. I can’t feel comfortable if everyone else isn’t feeling comfortable. So I’ve gotta do whatever I can do…

People who aren’t familiar with your body of work might be surprised that 1969 is such a rock or rock/blues record.

AC: That’s always been a thread through my work, but it would have been more of a thread if it wasn’t for my record company. That’s why I stopped recording for so long. I was a bit naïve when I signed and I first got into it. I didn’t realise that if you signed to the R&B or ‘black’ side of the record label, they expected you to cater for only a certain audience. I didn’t get that that’s how it worked. I’d have the record company guy pointing out the R&B section, and saying "Can you give me something a little more like this?" And it was stuff that I knew, but that I would never in my worst nightmares have wanted to record myself.

So if people are coming to this expecting it to sound like [1985 single] ‘The Dance Electric’, they’re in for a shock.

AC: ‘The Dance Electric’ was cool, because that’s something Prince wrote because he knew how politically-minded I was back then. He said "This might be something you like…" But no, if they’re expecting ‘The Dance Electric’, they won’t get that. That track was made eons ago: they probably don’t even make those kind of instruments any more! It’s vintage. If you can find it, you’ll be lucky. Although I’m sure they have it at Paisley Park…

1969 does feature some throwbacks to your early career, though. You’ve got William ‘Hollywood’ Doughty, the percussionist from your and Prince’s early band Grand Central, making an appearance, for example.

AC: Oh yeah, a lot of people don’t know that! He’s one of the original members of our very first band. In fact, I’m doing a show when I go back, and I’ve asked him if he wants to come up and play.

Speaking of partial reunions, you’ve played some shows with [Prince’s 90s band] the NPG, doing Prince songs, haven’t you?

AC: Yeah. You know, it’s very bittersweet playing his songs. It was fun, but only because his songs are amazing and he’s an amazing artist. His body of work is unbelievable. After I left his band, it’s hard for me to say I was a Prince fan, because we were too close, and it’s hard to be a fan of your brother, which is how I think of him. So I never looked at it like that. But when I left, even though I didn’t listen to a lot of his stuff, I’d maybe hear it on the radio. The only time I really got it was when he’d ring me up and say "Hey man, I really want you to hear this album." Normally I’d be in a club and he’d see me and send his bodyguard over, which was a bit weird, but I’d say "When he comes to get me, then I’ll go!" So a lot of times I’d say "No". But sometimes I’d say "Alright". Like one time I was with Jody Watley and Jermaine Stewart [both of whom Andre produced], and one of his bodyguards came over and said "Prince wants you to go up to his house", and I said to Jody and Jermaine "Do you wanna go?" and they were like "YEAH!" So we go up there and hang out, and Prince plays me Sign ‘O’ The Times. Which was a four-album set, at that point. He said to the other guys "Do you mind if me and Andre go and hang out?" So we wind up going upstairs and he plays me this thing which was like an epic. It was amazing. But I was like "It’s too long!" He said "What do you mean it’s too long?!" and I said "It’s way too much, man! You’ve got to narrow it down." And I said "Firstly, you’ve also got to just give people a chance to digest and take in the last album you had out. And he was like "I can’t do that!"

Which was a bone of contention with Warner, his record company, of course.

AC: Yeah it was. And he did end up cutting it down a little bit. But that was a great album. But anyway, performing his stuff is bittersweet for me because it’s fun, but it’s bizarre doing it without him.

The Revolution have been doing a similar thing recently, with reunion shows, of course.

AC: Yeah, and I did the First Avenue [Minneapolis club, as seen in Purple Rain] shows with them, and then I did the NPG ones, and now I’m done. It was good, and the reason why I did it was that fans in America and in Paisley Park and at First Avenue were really adamant about wanting me to do it. And Bobby [Z, Revolution drummer] said "You gotta do it" and Prince’s brother said "You gotta do it", so I said "Fine". And then the NPG said "You gotta do that", which originally was supposed to just be a few shows in Europe, but it turned into a bunch, and we finally did the last one. And I like the guys. As musicians, they’re awesome. Prince obviously had some unbelievable bands. Playing with those guys was a dream. But I think that for people who are truly Prince fans, he already left so much for us to get through.

True. We’d need several lifetimes to get through it all.

AC: Yeah. And I’ve got tons of stuff that people will never hear. But I think it’s better left, probably. It’s hard to say, because it probably isn’t gonna happen, but I was gonna say it’s better left the way he would want it to be left. Knowing him, he wouldn’t want any of that stuff coming out.

The unreleased material in the ‘Vault’ at Paisley Park?

AC: Yeah. But then again, you never know. Because he would have destroyed it if he never meant for anybody to hear it, right? If he didn’t destroy it, he probably wanted for somebody to hear it at some point, so… You know, it’s an interesting thing: when you know somebody really well, sometimes somebody who doesn’t know them so well might know more about them! Especially when it comes to Prince. Because he’s so smart. He thinks about stuff, in a very kind of calculated way, but not in a bad sense. I mean, I’m brash. I’m like "I’m just gonna do it. Let’s just do it." And he’s more "Now hold on. Wait a minute. What are you gonna do? How are you gonna do it?" It’s just thought. He would think about everything, and play it out: "Well, if we do this, that could happen. Hmm." It’s almost like coaching a basketball team. It’s strategy. If I learned anything from him, in that sense, it’s strategising things to make them work in a way that might be most favourable for you in the long run. Connecting that to The Vault, and what might happen to that, I can’t think that he didn’t think of that. Because he always thought about everything to some degree.

At this point, I ask Andre some bass-related questions for the November issue of Bass Guitarist magazine. You can read the whole thing here, but the main points are that he accidentally smashed his dad’s upright bass at the age of three (possibly precipitating his parents’ divorce), that he began by learning to play sax solos on the bass, that his first bass was a Fender Jazz which he stole from someone’s living room (only to karmically have it stolen from him after a gig), and that the bassists he most admires are Stanley Clarke, The NPG’s Sonny Thompson, and Sly & The Family Stone’s Larry Graham. Then it’s time to dig a little further into Andre’s memories of Prince and his thoughts on the evolution of the Minneapolis Sound.

I’ve heard conflicting opinions on the Minneapolis Sound from some of the major players. In her Red Bull Music Academy lecture, [long-serving Prince engineer] Susan Rogers argued that the Minneapolis sound was entirely Prince’s, and that he put together ‘rival’ bands like The Time in order to create the artificial impression of a thriving, competitive scene. However, at the recent Purple Reign conference in Salford, [former Prince guitarist] Dez Dickerson claimed that sound emerged organically from jamming sessions between yourselves and Prince. Furthermore, in the BBC4 documentary Rock’n’Roll Guns For Hire, [Revolution members] Wendy & Lisa argued that Prince’s bandmates should be given greater credit for co-writing his songs. Who’s right?

AC: Oddly enough, I think all of them are right to a certain extent. It depends on your starting point: where it became successful? Because Prince obviously did create The Time, no matter what anyone says. But Jesse Johnson played a part, because they’d have these jam sessions, and Prince would come along and cherry-pick the good parts from the jam and create a song. That’s just a fact. And he was in a position to either give credit or not give credit. And I know that, because I wasn’t given credit for a lot of the things I did. There were a lot of songs that were jammed on, that then became mega Prince songs…

Do you have any particular songs in mind?

AC: I’m talking about ‘Controversy’, because that started with a jam that we were working on before Prince even showed up to the rehearsal studio. I didn’t really think about it too much, because he and I grew up together, and us creating things together was just a natural thing. So I never thought about it in terms of "Oh, that was my song!" or "He’s stolen something from me". But when you put other musicians into the mix, in addition to the two guys who have very obviously been working together and living together, they’re gonna say "We were jamming on that before he even came. That was a vibe that Andre started when we were jamming." And to them, that makes it my song. And Prince went away and recorded it, and he came back literally the next day and said "Hey guys, you’ve got to check out this new song." And it was the same thing we’d been jamming on! I thought it was great, and he’d written lyrics for it, and the other guys were like "Er, that’s the song we were jamming on!" and they made a big thing out of it. But I never did.

You’ve never gone fighting for a songwriting credit on ‘Controversy’?

AC: No, not at all. Because they way I looked at it, and maybe it’s my naivete, was that he knows what I did. And at some point he should probably give credit, because it’s not like I can’t write songs like that, still. And thank goodness I’ve written other songs and had hits, so it’s not like I’m some guy where that’s the only song I ever wrote and it’s so precious.

So what’s the deal with ‘Do Me, Baby’?

AC: That’s different. Because Prince had asked me and Pepe Willie [early Prince collaborator, mentor, and distant relative] to write some songs for a musician who was Willie’s uncle, who was in [legendary soul vocal group] Little Anthony And The Imperials. And that song was musically something that I’d written. Oddly enough, I’d written it for my girlfriend of the time. It wasn’t called ‘Do Me, Baby’ but some of the lines were the same, and the music was the same. I’d written it for my girlfriend and it was called ‘Ooh Whatcha Do’, or something like that. She had a recording of it, and Pepe Willie had a recording of it, various people had a recording of it already. So that’s why it became such a big deal. Then I forgot about it, because I write a lot of music. But Prince didn’t forget about it. He was like "That was a cool jam!"

And you were gone from the band by the time ‘Do Me, Baby’ came out?

AC: Yeah. When it came out, I was like "Wait a minute…" But even still, by that time I think I was doing Jody Watley’s stuff so I didn’t make a big deal of it. I stopped doing interviews around that time, because people kept thinking I was jealous or whatever, or that I had all this anger about Prince.

You don’t seem like a very angry person.

AC: No, I’m not, that’s the thing! And I have to thank Adam Ant. He educated me about a lot of things, in terms of how to deal with talking to the press. Because I’d blurt out things that would sound absurd to somebody who didn’t know the history. And obviously, if Prince didn’t tell someone the history, they wouldn’t know it, because half of it was just he and I. It was like, if I said "Yeah, I wrote this song" or "I put that band together" or "I brought Morris into The Time", people would just laugh at me. And that was offensive to me, because it’s reality.

You were literally a family, in Grand Central, because your sister was in the band, and Prince’s cousin was in the band, and it was so tightly-knit. It wasn’t just a bunch of random musicians.

AC: Yeah, people know that now, but they didn’t know that then. So when I was saying it, they were literally laughing at me like I was making it up. And for the kind of person I was back then – I’m a different person now – I took it personally: "It’s not funny! This is what happened!" But people know it now. My sister was in the band, his cousin was in the band, my sister made all those outfits, not the clear pants but she made the Prince coats and so on.

On the subject of clothing, how did you feel about having to go onstage in basically nothing but underwear?

AC: That was my idea!

Were other members of the band a bit more reluctant?

AC: What was there to be reluctant about? You have to understand, they were hired. It’s different from me and Prince starting a band and going off and getting a record deal, and him saying "Would you do this with me? I can’t do it without you." It’s a big difference. I come with what I come with, and I’m gonna be who I am. I’m gonna wear what I want, and I’m gonna do what I want. If I can’t, I’m not gonna be able to work in that situation.

If we define the Minneapolis Sound as being funk with an electronic edge, that was even there with Lipps Inc, who you later worked with but who weren’t part of Prince’s empire. Maybe that stuff was just in the air?

AC: Well, the Minneapolis Sound was really created by the environment of Minneapolis. And that includes the radio. There was one black radio station, but otherwise it was just pop and rock. And as Grand Central, we would play a lot of rock. We would play Grand Funk Railroad and that kind of stuff. And because we didn’t have a horn section, we’d get my sister to play horn lines on the organ. We didn’t have a synthesizer at the time. So that’s how that vibe was created. But like I say, it depends when you’re talking about. Because Prince did do The Time, Prince did do the Vanity 6 stuff, and that created an aspect of the Minneapolis Sound, but when I left and did [debut solo album] Livin’ In The New Wave, that was a whole different kind of thing. And having been part of what I was a part of, I didn’t want to do what those guys were doing. And all of it is the Minneapolis Sound. So what Susan Rogers is talking about, that’s all part of it. But then if you look at Dez, he was in a band before he joined Prince’s band, and he very much had his own thing. And that’s why we thought he was such a great idea, because then it would be three guys that could handle the stage. Because if you look at it, Prince was never the centre. When we were in Grand Central, he was on this side of the stage, I was on that side of the stage, and we had our percussionist William Doughty who was in the middle. When we did the first Prince show where he was in the middle himself, he had complete stage fright!

When you look at how shy he was in some of that early footage, most famously American Bandstand, he needed some extrovert guys around him…

AC: And it worked out really great. We figured Dez could work the left side of the stage, Prince could have the centre and I’d have the right side of the stage. And that was the whole idea.

What age were you when you met, you and Prince?

AC: Seventh grade, so aged 12 or 13, something like that. We grew up in a really poor part of Minneapolis, and my mother had started having kids at 15. She was pregnant at 14, and had my eldest brother at 15. And my dad was very old school, and adamant that she shouldn’t go to school and have an education, although she was working. So they divorced, she went back to school and got an education, and moved us out. So I went to a different school where I didn’t know anybody, and I didn’t wanna be there. It’s that classic thing where you’re the outsider and everybody else already knew each other. And I’ll never forget, it was the first day and I looked down the school line at all these people, and I saw this one kid who looked odd. And I remember thinking "He reminds me of me." I was always the outcast and the weirdo, even in the place I’d left. I didn’t have many friends. I think in my whole life I’ve probably had five friends, haha! I don’t know what that means…

So you decided to make a new one?

AC: Yes. I saw him and I thought "I’m gonna go and stand next to that guy." So I said "Hi, I’m Andre," he said "I’m Prince", I said "What do you do?", he said "I play music", and "Oh, so do I!", and we got talking about it, and the next thing you know we’re over at his dad’s house jamming. And he’s playing ‘Man From UNCLE’ and ‘Peanuts’, and nailing it. And his dad had a four-string ukulele which I started playing, and Prince said "You can play!" and I said "So can you!", back and forth. But the funny thing, which we never knew at the time, was that his dad had a bunch of pictures on the piano, of trios, cos his dad was a pianist, and I’m looking at them and I see this guy, and I thought "God, that looks like my dad, except he has hair." And Prince was like "You should ask my dad, because he’s gonna be here in a little bit." But he gives me this whole thing about how his dad’s real ‘church’, so I have to behave in a certain way. And his dad gets there and he’s looking at me cos I’ve got this big ‘fro, and an apple cap over it, and I look like I’m from the wrong side of the rail track, and his dad’s wondering "Who’s this kid in my house?" It was like a one-bedroom apartment with nothing in it except this piano and a chair and these beautiful stairs. And he comes in and he’s totally stoic: [gruff voice] "What are you doing here? Who are you?" Prince goes "Dad this is Andre, we just met at school". And I said "Excuse me, but do you know who that is?", pointing at the picture. And he looked at the picture, and looked at me, and he just started laughing. And I was like, "What’s so funny?" He kept saying "Oh my god!" He must have said "Oh my god!" fifty times. Then he says "You’re Fred Anderson’s son!" Then he grabs me and says "You guys [Andre and Prince] used to play together when you were kids! I thought you looked familiar from something." And it turns out they used to go to this Seventh Day Adventist church. And it all came back to me. I remembered in the church there was this bathroom stall, where they were re-doing it and there was a deep hole, and some kid had fallen in. And we were next to the hole, looking down there. And me and Prince looked at each other, and I said "Are you helping him?" and he said "Nuh-uh", and we walked away. And that was the last time I saw him until the school gym, all those years later.

Is it true that Prince’s parents forbade him from seeing you at one stage, because you were a bit of a wild child?

AC: That’s absolutely true. I pulled up outside his mom’s house, when I was 14, with a white Cadillac. And I could hardly see over the dashboard. I’m honking on the horn, expecting Prince to run out, because finally I had this buddy I could hang out with and relate to, and I thought we were gonna joyride in this hot car. And his mom comes out, hands on her hips, "Whose car is that?!" And now I’ve gotta start answering questions. So I start lying: "It’s my uncle’s!" She’s like "Uncle who?" I said "My Uncle Tommy!" She says "I know your Uncle Tommy! He wouldn’t let you do that." So finally I drive away and she tells Prince "You can’t hang around him no more." So I thought, what if I come back on a mini bike? So I came back on a little motor scooter, "Can Prince come out and play?" and she’s like "NO!" Then I came round on my bike, this big over-the-top bike, and still no. They made him do yard work, anything other than hang around with me.

So how did you end up living together?

AC: In the end he ran away. I get a knock on the door and he’s there: "Man, can I come and stay with you guys?" I said "Yeah, it’d be great, but you’ll have to talk to my mom." So my mom talked to his mom, and she said yeah. I think they thought it would only be temporary but it wound up being six or seven years.

Did he always seem musically special? Or was he, at first, just one of the guys?

AC: He was always musically special. From the first time I saw him play ‘Man From UNCLE’, I thought "This guy is good." I thought I took music seriously. I had this thing: I would always say "There’s somebody, in California, that is doing what we’re doing, except that they’re practising right now", while we’re sitting around watching [sitcom] Welcome Back Kotter Because that was one of his favourites. And I’d say "We need to practice." He was the only person at that time who took it as serious as I did. Because I was adamant about being successful: we we’re gonna make it. I wanted to be up there with The Jackson Five. I always thought "We can take them out!" I literally said that, all the time.

So that Battle Of The Bands mentality gave you a competitive edge?

AC: Oh, absolutely. That was my way of breathing, at the time. I would literally challenge other bands. That’s how we would get gigs. If a band was playing, I would go up and yell at them, "We’re better!"

That competition between bands, fictionalised in Purple Rain, was based in reality?

AC: It’s a very PG-rated version of what really went on. And I know he wasn’t going to give me credit for any of that, but it was what it was. That was how we got gigs.

I don’t know if I’m reading too much into the lyrics of the title track of 1969, with the lyrics about missing someone, but is that about him at all?

AC: You know… [He thinks for a long time.] I think in some ways. Put it this way: it’s not overtly about him, but I think subliminally there are aspects of our relationship in that song. But there are also aspects of past girlfriends. It’s about letting go of something: you know that adage, "If you love something, let it go. And if it’s meant to be, it’ll come back." But it’s also sad and tragic when, in one particular case, there was a girl I met who I was in love with, but she got married and got pregnant, and moved on. And I always wondered what her life had become. And with Prince, every time I went to see him, I was always curious: "Are you happy?" Because he didn’t seem happy. When we were growing up, we had so much fun doing what we did, but then I’d see him and I’d say "Who are these people? Who’s got your back?" Because that’s how we worked. And he’d give me a breakdown of who everyone was, blah blah blah. But he didn’t seem happy. But since, talking to the NPG and other people who knew him, it seems like he was happy, or happier than I thought he was.

When you supported The Rolling Stones with Prince around the time of Dirty Mind, is it true the audience booed you?

AC: First of all, that was the first gig with Mark Brown as the bass player, because I’d left!

Damn, I need to go back to Prince School. Sorry.

AC: No no no, it’s interesting, because it was their first gig without me, and a lot of people get that wrong. A lot of people said "If you were there, they never would have booed us." Oh, they would have booed us! The only difference is that I would have caught stuff and thrown it back, because that’s the kind of person I am. Or beforehand, if it were me and Prince, I would have thought about how we approach this. "Let’s make sure we don’t do things that are offensive to this crowd. Let’s give ourselves the best chance to succeed." And when I played with the NPG recently, it was an almost identical episode, because they were opening for the Red Hot Chili Peppers. And with the show they’d put together, it would have been great if they’d been opening for Mary J Blige or something. But I said "Prince has this amazing catalogue. If you guys, as the NPG, want to do more shows with the Red Hot Chili Peppers, I would choose different songs. I’m not gonna be around, but…" They were doing ‘Jughead’ but they weren’t doing ‘Cream’, you know? And if there’s one thing I learned from Prince, it’s how to strategise things.

You found yourself in an odd situation circa Dirty Mind. You were there in the promotional photos, there on the inner sleeve, there in the videos, and obviously there onstage, but you weren’t credited. If I go online now and look at Dirty Mind on Allmusic, there’s no band listed. You were in, and out, at the same time.

AC: To be honest with you, I didn’t want a credit. I mean, in retrospect it would have been great because obviously I was very much involved. The first album [For You] blew my mind, cos I only found out recently, when I did a South By South West thing with Dez, that I wasn’t credited on that. Which is strange, because not only did I sing and play on that thing, but I was there. Everyone else is credited, Bobby Z is credited, and Bobby wasn’t there! I was there. I wonder, sometimes, what the idea was behind that. Because again, knowing Prince, there would have been a concept. What was the concept behind absolutely no credit for anything? I have no idea. I’ll leave it to someone else to try and crack that code. Because anyone who was around knows what I did and that I was involved.

Is it true that you had the curly white ‘cloud’ guitar from Purple Rain first (but the bass version), before he got his?

AC: Yeah. But it wasn’t white, then. It was brown. I got it in San Rafael, California. Because we were driving around and I saw a music store, a guitar shop. And I said "We should go in." So we stopped, and he pulled out a guitar, and I saw this bass and said "You’ve got to get this, oh my god." Because I didn’t have money, and he had a recording budget. So he bought it, and I played it on, I think, American Bandstand or Midnight Special, one of those shows. And that became the ‘Cloud Guitar’, and he patented it after that. I didn’t get any credit for that either, so at least he’s consistent!

If we’re talking about Purple Rain connections, you even wrote a song for Evelyn ‘Champagne’ King around that time called ‘Let’s Get Crazy’…

AC: It’s interesting you should being that up. You wanna hear a funny story about that? I did that song in Sunset Sound, and he was recording at the same time. And I remember him and Owen Husney had a little thing during that session, because Owen used to manage him. And I’m riding down Highway 100 in Minneapolis, minding my own business, and I’m living in Medina and he’s living, I think, in Chanhassen. And this purple car comes honking alongside me, "Pull over! Pull over!" and I look and it’s Prince. And I pull over and he says "Man, I just wanna tell you, I’ve got this song coming out called ‘Let’s Go Crazy’ and I know you’ve got that song ‘Let’s Get Crazy’ and I don’t want you to think…", and I’m like "Dude, it’s cool!"

Is it true that when you were on tour, you were sometimes fined by Rob Marchner, the tour manager, for lateness?

AC: Never. Never fined, because I would just quit. But you know, he did leave me and Prince behind! Because we were addicted to those video games, Galaxian, Pac-Man and all that kind of stuff. And we were playing one of those in the airport. And Rob thought he was going to teach us a lesson by leaving us. So he leaves me and Prince, and we finally pull our heads out of the games, and we’re like "Where is everybody at?!" and they’re gone. So we call Rob: "What happened?" and he says "Well, you guys didn’t come out so we left you." Next gig, new road manager.

Was there really a profanity jar? According to Dez, there was…

AC: Not in my time. All of that stuff might have happened after I left. I mean, you’ve got to understand I wasn’t hired. Prince asked me to join, literally, and when someone asks you, they take you as you are. And part of Gayle’s [Chapman, keyboardist] problem was that she was very religiously-oriented and I used to cuss all the time. And she’d say "Can you stop cussing?" and I’d be like "Fuck you!" Cos I was who I was, and there was no way I was gonna be anybody else, for anybody else. Especially for someone I don’t even know that well. Why am I gonna change my crude self?

I met Little Richard once and I asked him what he thought of Prince. Because of the obvious similarity. And he said "Well I’ll tell you this: he sure likes me." And then he said "He’s great, but I just wish he wouldn’t use so much profanity…"

AC: Hah! I met him once and I went out to lunch with him. Because they were doing a movie, and they thought I’d be great to play Little Richard. So we met in what I think was called the Continental Hotel at the time, and he was living there. And we sat down and ate French fries, and he said "You too pretty to play me!" And I thought "I don’t know what that means!" Because I didn’t think of myself as being a pretty guy. He was like, "There’s no way you can play me!"

That utopian fantasy on the Dirty Mind album ("White, black, Puerto Rican/Everybody just a-freakin’…"), and that feeling of racial and sexual unity you were expressing then, is a long way from the reality of the world now, and the situation you’re singing about on 1969.

AC: Absolutely. And for all the things Prince does get credit for, I think that’s something he doesn’t get enough credit for: trying to make that statement of freedom. Freedom of expression in your music, and in terms of whether you’re gay, straight or whatever. That seems to get lost, among all the discussion of his musicianship and his guitar-playing. And it was part of the statement we were trying to make in Grand Central, so I was happy to see him carry that through in other songs.

What was the breaking point, with you leaving Prince’s band?

AC: Well, I said I was going to be there for three albums. First of all he wanted to do like a Brothers Johnson thing: "I can’t do this without you!" and I was like "But they signed YOU", and he said "Well maybe we can do a Brothers Johnson thing", and I was like "No, man, they signed you. This is your moment. I got your back, and if you’re doing a three album deal or a two album deal, I’ll do what I can do for you." And the breaking point is when you start to realise how the record business works, and you start to feel you aren’t being compensated or given the recognition you think you deserve. And also thinking "There’s a lot of me invested in this thing, and if you don’t leave soon, there’ll be nothing left of me to salvage." So I thought I should let him carry on, and try to establish myself.

How did you feel when you heard his subsequent great records? For example, ‘When Doves Cry’ which famously has no bassline? As a bassist yourself…

AC: I thought that was the most brilliant record I’d ever heard. Literally. Bar none. And I was just proud that it was somebody I knew. I heard it and I was like, this is the shit. I literally think I pulled over when I heard that. I remember where I was. I was in California and I heard it and thought "Oh shit, this is dope." It wasn’t even about bass or no bass, because I don’t think like that. It’s about how it impacts me, and when something impacts me like that, I don’t think about production. I just think about how it affects me, and it’s the same with Stevie Wonder’s music. I would be the same with his music: something would come on, and it would be like, "Oh my god." It’s about the whole thing. Maybe I’ll think about the production later. I’m sure you’re the same, as a music fan…

I have a similar memory, with ‘When Doves Cry’. I wasn’t driving – I was walking down the street – but it stopped me in my tracks: "What is that?!"

AC: Right! You hear something that’s fresh, and you wanna grab people and turn them onto it. And that’s what music’s all about.

Speaking of production, you’ve done so many production jobs yourself – Tom Jones, Adam Ant, Jody Watley, Pebbles, Jermaine Stewart and many more – but what’s your favourite one to look back on?

AC: Adam Ant. Oh man. I just had so much fun. Adam is just an amazing person. Working with him and Marco [Pirroni], I would have done that for free. I was a big fan, to begin with. I’m not a fan of many people, because I don’t have that kind of mentality, but I was a fan of Adam. And he’s such a smart man, always learning and studying. A student of history, a student of fashion, a student of everything. And he took what he did so seriously. It made me a better person. And Prince was the same: he made me a better person. I love it when someone can do that. I’m a very secure person, and I don’t feel like I need improving, but if someone can come along and do that, wow. Adam was like that. We had so much fun doing that project. He wanted me to do his next album, but it didn’t happen. He was into boxing, I was into boxing, we were living in California for a while, we hung out. He’s one of a kind. That’s probably my fondest memory. Tom Jones was fun too, getting to know him. But Adam, by far, was the best.

There’s a story that Prince came into the studio one day, clutching a copy of the Prince Charming album, saying "This is how we’re gonna dress from now on." The frilly shirts, the jackets…

AC: Well, no, but I know how that proceeded. When we did the first European tour, I’d already said I was quitting at that point, but I said "You know what? I’ll do it for free. Keep your money." And I did it, and I went home broke. But the press said such bad things about Prince after that London show. You’d have to read it, and you’ll see. We’d have been wearing the lingerie and the trenchcoats, and reviewers said something about his fashion sense, that he wasn’t very stylish. And Prince took it really, really personal. And that’s when he went back, and my brother had given us a book called The British Invasion, and it had Adam and Bow Wow Wow and all those bands, and Prince loved the whole way Adam dressed. I mean, since you brought it up, because I wasn’t gonna say anything! But there is some truth to that story.

The song ‘Point And Click’ on your album deals with the internet and the way it affects musicians. What’s your take on that?

AC: When I was working as a producer, I became friends with a lot of, I guess, giants of the industry. Corporate guys. Guys who owned EMI, SBK, all that kind of stuff. They used to ask me about artists, who to sign, all that kind of stuff. They came across Tracy Chapman, and asked me if they should sign her, and I was like "Obviously, yeah!" And then Neneh Cherry, "Obviously, yeah!", Wilson Phillips, and blah blah blah. They asked me if I wanted to be an executive and have my own jet, but it wasn’t my thing, so I said no. But when Napster happened, I called them up and said "You know what? You guys might want to get a handle on this. Because if people start getting music for free, they’re gonna always want music for free." I said "Put viruses in 90% if your music so that when people download music, they’re not sure if they’re getting pure music or something that’s gonna corrupt their whole hard drive." They’re like "We can’t do that, we’ll get sued!" and I’m like "If you don’t do that, you won’t have a business." And we went back and forth for a minute, then I said "You know what, whatever. I’m just telling you." And it’s funny, I ran into one of those executives, who was running things at the time, about ten years later. And he’s like "You know what? You were right." And "Point And Click" kind of came out of that. People feel like they should get music for free, and artists are at a point where, luckily I’ve done things in my life that have made money and I’m able to sustain, though I’m by no means rich or anything like that, but I’m OK, but if I were starting out now, I’d have to think twice about being an artist. Because you can’t have a lifestyle. And artists like Prince, or Jimi Hendrix, if they were starting out now, they probably wouldn’t exist.

In this country, we’ve reached a situation where an ever-narrower section of society, largely the upper-middle and upper classes, are even able to afford to form bands.

AC: Right, this is my whole point. Not only that, but it affects the type of music that’s able to be made. It’s loops and samples and stuff that they aren’t necessarily creating themselves: they’re creating something from something. And that’s what "Point And Click" is all about: "You point and click me out of business." All the rebels, the defiant ones who made the music business what it was, are gonna be history. If you don’t support them.

Andre Cymone’s 1969 is out now on Blindtango/Leopard.