“The question arises whether the small-scale model or miniature, which is also the ‘masterpiece’ of the journeyman may not in fact be the universal type of the work of art. All miniatures seem to have intrinsic aesthetic quality – and from what should they draw this constant virtue if not from the dimensions themselves?” Claude Lévi Strauss from The Savage Mind

“At junction 2 of the M40 there was the Bekonscot Model Village, a half-acre of Little England writ very little indeed. If the sign for the model village on the M40 had been dropped on Bekonscot it would’ve flattened it – why, I wondered, was no one else preoccupied by this?” Will Self, talking about his obsession with scale

IN THE LAST MONTHS OF WORLD WAR II, Japanese film director Ishiro Honda was captured during a tour of service and held in a Chinese prisoner of war camp. After the end of the fighting and release, his journey home took him directly through the decimated city of Hiroshima. This would have a profound impact on him, as would something that occurred nearly a decade later. He was working on a monster movie during 1954 when he learned that the crew of a Japanese fishing vessel working in the South Pacific had been killed during the testing of an American nuclear weapon. The atomic bomb was many times more powerful than Little Boy – the payload of the Enola Gay – released over Hiroshima. This real life incident became the opening scene of his movie Godzilla or Gojira. The movie was perhaps the most important piece of political film making released in the post war years, not that you would know it if you’ve only seen the bowdlerized American cut. The really terrifying star of the film was not the giant aquatic lizard but the razed city blocks and decimated vehicles it left in its wake. Either way the Kaiju (literal translation: strange beast) or giant monster of the nuclear age was born.

Back in America, outside of Hollywood, it wasn’t as if people were any less cagey about the brave new world of nuclear testing. 1954 also saw the release of Them! concerning a race of outsized carnivorous ants created by bomb tests in the deserts of New Mexico. Of course, these films didn’t suggest that people were actually afraid of the eventuality of gigantic mutant animals and insects roaming the world, rather than the new scale of destruction that the hydrogen bomb threatened to wreak. It would be years, if not decades, before people realised en masse that they now had more to fear from the micro not the macro. Cities had been bombed before and would be bombed again but the new threat lay in the savage efflorescence of cancer clusters, the strange bloom of metastasising cells birthing a remorseless sickness that would infect the land, the buildings and even the wind. These were bombs that would keep on exploding down through the generations. Perhaps the most chillingly predictive sci-fi film of the atomic era then was The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) which featured Grant Williams as the everyman Scott Carey coming into contact with (yes) a radioactive cloud from a nuclear test before progressively getting smaller and smaller. His contact with miniature life was all the more shocking because it was with a normal garden spider. He was forced to confront the brutality of nature on it’s own terms. This was no radioactive sci-fi monster but the stuff we ignore on a daily basis because it’s just too small for us to see.

In the movie he defeats the tumour-like spider with a sewing needle but only just and then his troubles are not over: the film does not end with a good prognosis for the protagonist. According to his own narration, it seems he may keep on shrinking until he reaches the atomic level. He will waste away until he becomes nothing… a fitting metaphor for radiation sickness and then death.

Of course man needs to shrink down to the size of the insect (or arachnid) because they cannot grow to ours. The spider has been around for at least 300 million years and will almost certainly still be here long after we’re gone. They can’t get any bigger than they are now because thankfully they don’t have the right breathing apparatus. They take oxygen up directly either through gill-like book lungs or through their porous chitin skins. You are only here because the roll of Charles Darwin’s dice didn’t blindly produce spiders with mammalian lungs. (And wings.)

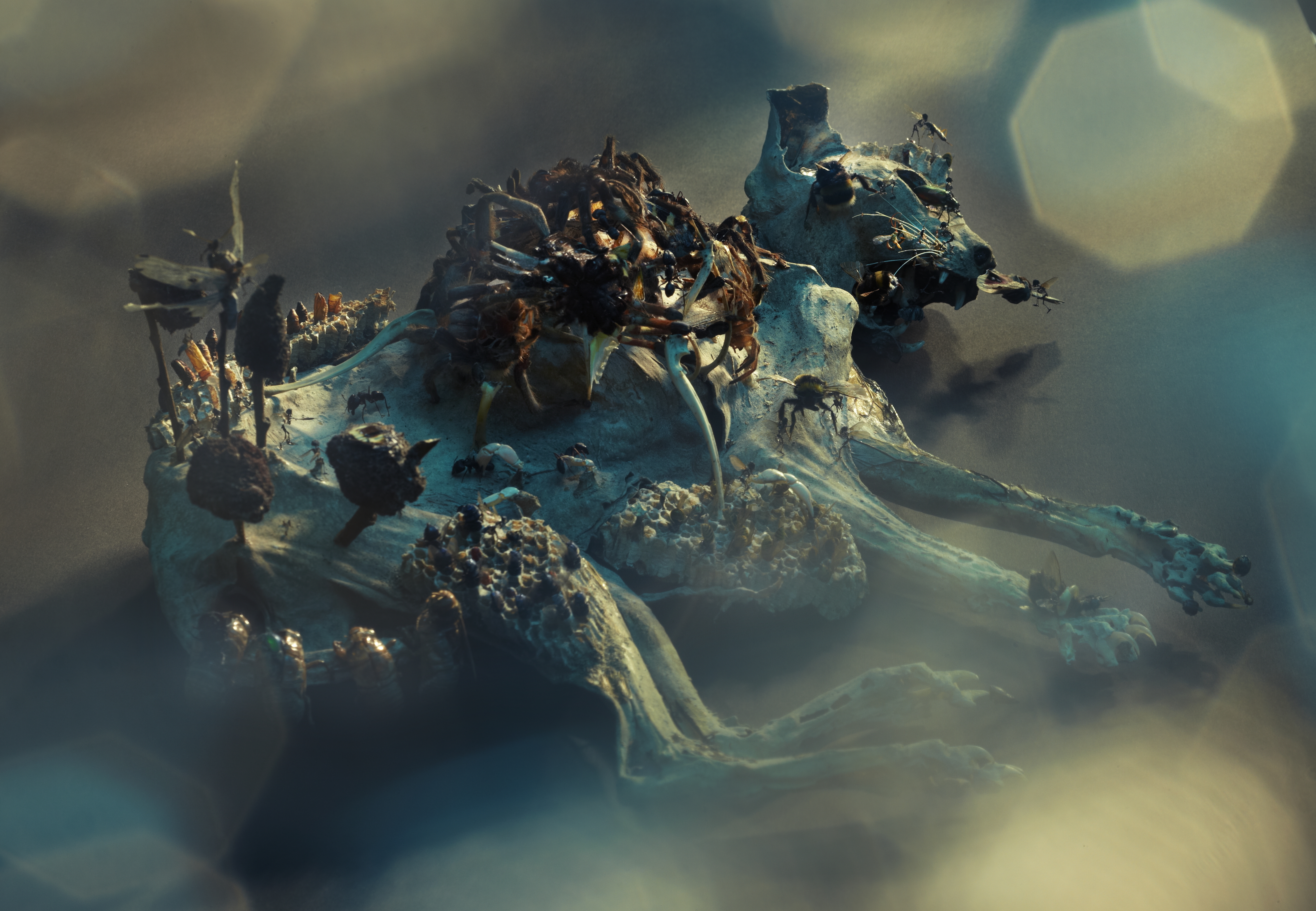

The battle for survival between humanoid figures and insect life is key to the exquisite art of Tessa Farmer but her work is the exact opposite of political/social allegory. When you look at the installation called Control Over Nature – which she produced as a direct response to the new album ISAM by Amon Tobin – you could be forgiven for not noticing the sublime peculiarity of what you are looking at. What at first glance looks like a swarm of insects hovering in the air, some dead birds, fragments of bone and the badly decomposed body of a cat, reveals itself to be a pulsating world just out of view, as rich in disturbing detail as a painting by Hieronymus Bosch or an installation by Jake and Dinos Chapman. By using natural materials on a micro level to produce an all-encompassing new whole, she was the ideal person to reinterpret the sonic vision of pioneering electronic musician Tobin; they both share a monastic level of devotion to their art and an almost fanatical level of attention to detail. This “synergistic” combination of physical and audio is a mosaic of infinite complexity. A thing of complete fractal clarity that gives up more and more detail, no matter how close you get to (seeing or hearing) it.

But if there is a sublime peculiarity to what you are seeing then this is only because there is a sublime peculiarity to what you are hearing as well. It is a measure of how restlessly curious and inventive Amon Tobin is, that the last time we heard from him in 2007,he was also working with insects; taking field recordings of the noises made by wasps and ants and turning them into Musique Concrète. Tobin’s inquisitive nature has taken him further afield into the realms of pure sonic innovation with each of his successive albums, so when he started dreaming up new ways of making music and manipulating sound for The Foley Room (2007) he began working purely with field recordings rather than just samples. One of his experiments involved taping the very language of ants themselves using the most sensitive microphones he could source and home made amplification units made from tin foil.

He explains how his methodology and philosophy of sound engineering has taken him into even newer realms of instrument design for ISAM, his 8th album: “I started out on my early records mostly interested in re-contextualising existing musical styles into new musical environments. It was key that the source material was identifiable to an extent in order to appreciate the new role it played when removed from its original context and placed in a new one. Making Supermodified (2000) and Out From Out Where (2002) I then got more into processing the source material often to a point where the origin of the sounds became unrecognisable and therefore irrelevant. By the time I got to making The Foley Room the emphasis had shifted entirely from the nature of the source material to what could be done with it. I was focusing on sound manipulation and design, all raw materials be they from traditional instruments or field recordings could be viewed as musically relevant and useful. With ISAM the shift has been to bring all source elements into a physically playable realm. Now all sounds regardless of how small or strange are built into playable instruments with properties limited only by the physical limitations I choose to impose on them. Synthesis of the field recordings, acoustic modeling and multi-sampling techniques allow for invented instruments to be created with impossible physical parameters.”

The extent to which Tobin can now ‘get inside’ the very sound and remould it, is reflected by the vocals on the album. ‘Wooden Toy’ features a breathless performance by a young woman, a creepy sounding old lady loans her voice to ‘Kitty Cat’ and what sounds like a toyshop come to life forms a choir on ‘Dropped From The Sky’. All of which are surprising fundamentally because they are all sung by Tobin himself. He explains: “The voices on ISAM were a natural extension of the synthesis techniques I applied to the majority of the other sounds on the album. I took an objective approach to all sounds including my own voice which once translated to it’s spectral components could be altered radically to become a string sound or percussion or simply formant shifted to change the perceived gender. In the most straight forward instances I created characters based on my own rather uninteresting voice to perform vocals e.g. an old lady in ‘Kitty Cat’ and a girl in ‘Wooden Toy’.”

Quite clearly when dealing with two such individual artists, one has to ask how their methods mirror one another’s: “We are both using familiar materials and reorganising them into unfamiliar structures. Tessa will take the head of an animal and turn it into a vehicle for battling fairies, I’ll take the sound of my chair creaking and turn it into a playable instrument.

“ISAM itself is based on building invented instruments that are still connected to familiar sounds as they harness physical properties of things we know to be real. This is important otherwise we’d be dealing with abstraction, which is arguably less generous in terms of allowing for an emotional connection to the work on the part of the listener. To draw a parallel with Tessa’s work, it might not have held the same intrigue had she made the fairies out of plastic instead of organic materials or indeed other insect parts.”

FARMER DOES INDEED USE JUST ORGANIC MATERIALS to build her dioramas of an imaginary world populated by fairies. These fairies, sometimes referred to as “Hell’s Angels”, are 10mm long intricate skeletons constructed from plant matter and soil with fly wings. They, and the world they inhabit are only partially visible with the naked eye. The insects (mainly hornets and wasps here) and the dead bodies of birds and small animals only give up their true nature when viewed through magnifying lenses. Using carcasses found on walks round North East London she weaves together narrative strands of folklore and fantasy with entomologically correct representations of insect life to produce celebrated art that has been exhibited everywhere from the The Museum of Old and New Art in Tasmania to the new Saatchi Gallery in London.

After leaving University where she made skeletons of various sizes, she realised that her impulse was to produce smaller and smaller work: “I wanted to make the fairies that size because I was becoming interested in insects. What I admire about insects is how… well, ingenious is the wrong word because how they are is down to evolution rather than ingenuity but the way they survive and they behave is mind-boggling. They have evolved to fill every niche in life. I love it that there is this whole other world that is part of ours, but also alien to us because it’s so unfamiliar.”

She explains that the obsession with putting humanoid characters together with insects (which she has been doing since 2003) has been an evolutionary process in itself: “I suppose by getting the fairies to insect size I was validating them for myself. It meant I could work at that scale and the fairies became contemporaries of the insects. The fairies have evolved because of what insects I’ve found or been given. I never kill stuff so the process of what I make can be quite random. I’m like a scavenger really, picking up dead things. It’s amazing what you can find just walking down the street. Last time I found loads of dead bumble bees, which was really odd. I don’t know why there were so many of them. If it’s a really hot summer I’ll find a lot of wasps.”

Just as the nature she is representing is red in mandible and claw; her humanoid figures represent the dark, violent and mischievous little people of folklore rather than the twee sorts of more recent times. Her research threw up some interesting discoveries: “Fairies go back to before Shakespeare to the Middle Ages when they were thought to be the souls of the dead; back then they were feared and associated with darkness. But then they became more benign towards the Victorian era. But even then if you look at paintings that portray them as pretty, whimsical things, they can still be quite dark. There were still representations of pretty but nasty fairies torturing animals and insects around them. Because the cities were becoming industrialized there was a subconscious fear of rural anarchy perhaps. It reflected a desire for modern order. My Great Grandfather Arthur Machen, wrote books that sometimes concerned little people. I didn’t know his work until I started looking into the fairies which is a weird but true coincidence. He was a supernatural horror writer and it was quite weird reading his stuff but quite inspirational as well. In one book, Out Of The Earth, little people pour out of the ground and wreak havoc and kill animals and children before going back into the pits of Hell. Which kind of made sense because my fairies are made of plant roots and came out of the Earth.”

Now, as we slide out of industrialisation we fear anarchy once more and not just in the countryside. What we fear is the collapse of society in itself, of man’s retreat away from civilisation and reason as the human race reaches an ungovernable size.

CONTROL OVER NATURE IS PERHAPS HER MOST AMBITIOUS WORK TO DATE, featuring multiple pieces, all of which refer to and which were inspired by tracks on the album ISAM. She describes the strange scene in the Crypt of St Pancras Church which greets the viewer: “A dead blue tit has six fairies standing on it. It’s ambiguous. They could be pulling the bird’s feathers out or looking for lice.

“The different pieces go with different pieces of music. The more frenetic tracks [such as ‘Goto 10’ and ‘Surge’] really suggested battle scenes where the hornets are battling the fairies.”

Another piece of the puzzle features a sheep’s skull which has been converted into a flying ship by the fairies using enslaved beetles. The eye itself has evolved several times over since life began on earth independently; Farmer’s little people are merely the most recent to discover a means of making inanimate objects take flight. The centrepiece of the installation however is the mummified pet, inspired by the track ‘Kitty Cat’: “I don’t think the fairies killed the cat but the cat has become a piece of architecture and they are living in it. It’s quite beautiful. It’s got this hollow where the bowels and intestines used to be and in the rib cage is now an amphitheatre. It’s like the entertainment area and you can see fairies wrestling with ants inside it. Onto the ribcage I’ve built a cage from tarantula skins and butterfly wings and bones and inside the cage is a mouse. There is a kind of farm where they use the cells to contain insects, in one of the sections they’re breeding fly pupae and in another section they’ve got wasps who are trapped in head down so they can’t get out. They’re being farmed.”

Another piece, made from the flattened body of a great tit, covered in silken cocoons was inspired by the meticulous research she has carried out into the parasitic nature of some social insects. She says: “This is based on the cocoons that some parasitic wasps make. They lay their egg in particular caterpillars. The larvae hatch and eat the non-essential organs of the caterpillar so it stays alive but with them inside, growing. And when they’re ready they chew their way out and spin these silken cocoons to hatch from. This is what you’re left with: the shell of a caterpillar covered in cocoons that wasps have hatched from. It’s really beautiful in a gory way. I also want to have a bird plummeting to the ground to go with the track ‘Dropped From The Sky’. I will have it being attacked by fairies – being speared by them.”

Tessa Farmer’s horrifically beautiful world of winged skeletons is one free of morality and individualism. Insects are so alien to us that they defy anthropomorphism in a way that fairies locked in combat with various taxidermied rodents or dogs or birds, for example, wouldn’t. She is adamant: “I’m not that interested in humans. My work is about insects and about survival. There is no moral element to this art. The insects don’t have morals so I don’t see why the fairies should. They just have to do what they have to in order to survive.”

In a sense Control Over Nature – as the double meaning of the title suggests – can be read as the struggle between nature versus nurture. Genes versus memes. Biology versus language. Insects versus fairies. A battle between the genetic information that creates what Richard Dawkins called a “survival machine” and the only partially useful by-product of self-awareness and intelligence that has developed accidentally from it. But what it can’t be read as, is a critique on human nature and human attitudes towards nature and the environment.

“The destruction of the natural world is not the result of global capitalism, industrialisation, “Western civilisation” or any flaw in human institutions. It is a consequence of the evolutionary success of an exceptionally rapacious primate. Throughout all of history and prehistory, human advance has coincided with ecological devastation.” John Gray discussing Disseminated Primatemaia or the Human Plague

THE MORE THAT INDIVIDUAL COMPONENTS OF THE HUMAN PLAGUE think of themselves as different to animals, the more bestial they become. All the worst atrocities of the 20th Century (Fascism and Communism) were born out of utopian idealism. There is no doubt that leading Nazis and Stalinists thought of themselves as exemplars of human civilisation but both wanted little more than an insect future for humankind. This is not a modern ill though, before the last century, the worst horrors that we wrought on ourselves and the environment still came from the utopian dreams, just those woven by religion or the enlightenment.

We are wrong not to think of ourselves as animals. When we think of ourselves as being superior to them we become unstuck. The famous humanist Ludwig Wittgenstein said, “If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.” On hearing this, the gambler and safari park owner John Aspinall laughed: “It is clear that Wittgenstein hadn’t spent much time with lions.”

If an ant could talk, unfortunately we could understand him. (Unfortunate because we would sooner ignore the unpleasant implications of what he had to say.)

AS WITH SCOTT CAREY IN THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN, British author Will Self also described a hapless character slowly disappearing out of view in his fiction work Scale. His protagonist visited the Bekonscot Model Village and then, while wandering round it found a model village inside that. Then while wandering round that, he found another model village inside that, then another inside that. The character ends up on a scale so small that what we would consider to be the normal laws of physics don’t apply any more. He becomes afraid that the quantum effects of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle will simply wink him out of existence.

Amon Tobin and Tessa Farmer are going deeper and deeper into their art, away from the macro and into the micro but they are fearless explorers like Alice disappearing down the rabbit hole, not cyphers of angst in a modern age. One gets the impression Tobin would break down his sounds even further into even smaller component parts until it would take a hearing system more advanced than our own to be able to discern what he was doing. And one can’t help but feel that Farmer would let her fairies grow even smaller, allowing them to wreak their mischief and havoc on the very genetic material we are made from. Both of them waging war on art’s new inner frontiers.

The Control Over Nature installation is open between May 26 and June 3 at The Crypt Gallery, St Pancras Church, London. More details on this and the ISAM album here