Alison Cotton by Kate Hockenhull

Along an unassuming terrace across from Sunderland Hospital stands the childhood home of Ida and Louise Cook, two sisters who orchestrated the rescue of 29 Jewish people from the continent before World War II broke out. All of this was achieved through their fanatic obsession with opera, which became the cover for their frequent trips back and forth from Germany as they smuggled the refugees’ property out the country.

Alison Cotton would often walk past that same terraced house as a child. She took viola lessons in Durham, and eventually became one half of The Left Outsides with her husband, Mark Nicholas. She has released solo work for a few years now, often spectral, ambient pieces with lyrics centred around historical events (a song off her recent album The Portrait You Painted Of Me references the 1962 Seaham disaster in which eight men and one nine-year-old boy drowned).

Her latest album, however, focuses entirely on a much more celebratory tale: the story of the Cooks. Cotton honours the sisters in Engelchen, but she engages with her inspiration far beyond sound or lyricism, incorporating their spirit of humanitarianism into the entire concept of the album. “I’d never dreamed I’d be making an album about someone that lived in one of those houses, yet here I am,” she says. “It just turns out that person is one of the most incredible people I’ve ever heard.”

Louise and Ida were born in 1901 and 1904 respectively in a middle-class, tight-knit family in Sunderland with two other siblings. Moving down to London as children, the sisters would grow up to work as typists for the civil service; Ida would eventually discover a knack for romance fiction writing and became a prolific author under the name Mary Burchell.

But the sisters’ lives really changed when Louise encountered a gramophone at her workplace in 1923. Recommended the latest Amelita Galli-Curci 78 at the record store, the Cooks rapidly descended into obsession that impassioned the women to save their money for two years so they could afford a trip to New York City to witness Galli-Curci’s commanding coloratura soprano live at the Met. From there, they visited Florence, where their penchant for photographing their stars landed them a friendship with another soprano, the larger than life Romanian Viorica Ursuleac and her husband, the conductor Clemens Krauss. And it was Krauss that introduced the Cooks to Mitia Mayer-Lismann: official lecturer of Salzburg Festival, fellow opera lover, and someone who happened to be Jewish.

In the years directly before the war, the British government did not make it easy for Jewish people trying to flee to this country from Germany and Poland. Numbers of Jewish refugees accepted were limited; those fleeing also had to prove they would not be a burden to the state. For this, they were required to present a large sum of money and sponsorship by a British guarantor – and even then only if they could substantiate plans to emigrate to another country (which was most often America). Only then could they find shelter in the UK. An added challenge, of course, was the Nazi party, who forbade Jewish people from taking their capital out of the country.

Mitia was the first person to make the Cooks aware of the refugees’ difficulties on trying to escape Germany; but soon afterwards the sisters began to devise a plan. Potential refugees would contact Mayer-Lismann for help, and Louise began to learn German to aid efforts. The sisters would travel to Croydon Airport in their cheap finery, with British fur coats tucked in the bottoms of their bags.

Then, they would travel to meet Krauss – who was Director of the Berlin State Opera and later Intendant of National Theatre Munich – who coordinated opera performances for the sisters to attend, and they would travel to the city in order to meet with refugees.

The sisters would smuggle the refugees’ valuables out of the country. Jewellery, furs, and watches were common items which could easily be sold in the UK to raise the funds to prove the refugees’ financial worth. The sisters would leave their own watches behind and swap the labels of the fur coats, restitching British labels to the German coats to avoid suspicion, and pinning precious brooches to their plain jumpers. To the average Nazi border guard, the sisters were simply spinsters adorned in overly ostentatious trinkets and costume jewellery… they were returning from the opera, after all.

Sailing back to England from The Netherlands on a Sunday, they would be back at their desks typing by Monday. They performed this routine for three years before the outbreak of war in 1939.

It is no understatement to say that it is the sister’s perseverance, humanity and spirit that allowed them to achieve such a monumentous feat. They were recognised as Righteous Among The Nations in 1964, a term designated to gentiles who saved the lives of Jewish people during the dark days of World War II. The Cooks would receive letters of thanks from those they had helped bestowing upon them the nickname ‘Engelchen’, a German term of endearment meaning ‘little angels’.

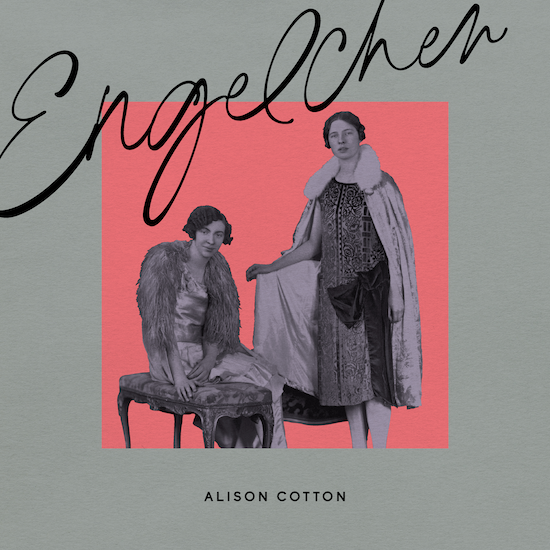

The sleeve of Engelchen featuring Ida and Louise Cook

Commissioned by arts charity Sound and Music to create her own project, Alison knew she wanted to spotlight notable figures from Sunderland. Dissatisfied with obvious answers like Lewis Carroll or Ada Lovelace, she came across the story of the Cooks and was immediately hooked. She began researching their story and read Ida’s memoir The Bravest Voices, falling in love with their charming quirkiness and endearing passion for music, the latter of which she found relatable: “They were queuing for opera tickets; I remember queuing for concerts in Newcastle City Hall. It was the 1920s and they’re doing the same thing.”

The album is also a general tribute to the Cooks and their sheer dedication to music, too – a quarter of Ida’s first memoir We Followed Our Stars is entirely about opera. ‘The Gramophone Circle Parties’ honours their regular listening events, collecting shellac 78 12"s of the latest opera records and hosting social events to listen to them.

Meanwhile, ‘Crepuscule’ is a cover of a song by Galli-Curci with Cotton transforming the Italian’s melismatic delivery and the original’s trinket-box instrumental into a duskier rendition in the vein of Julee Cruise: “There’s something quite otherworldly about it. I could hear myself doing something really different. I wanted it to have that feeling of being in a dark club.”

Of course their story has a profound resonance today. Cotton sought to understand the current challenges refugees face; she paired up with local support centre North East Rise to speak with a number of refugees for the album. Her main source was Elias, who was born in Egypt and moved to Somalia shortly afterwards before returning to Egypt for work. His story is captured in the final track of the album, ‘Engelchen Now’.

“He was working as security for the government, and people around him were saying, ‘You really need to get out’”, Cotton recalls. “Explosions were going off all the time. He couldn’t get back to Somalia because his visa had run out.”

The then 24 year old boarded five different flights to eventually arrive at Heathrow, where someone then asked for his life savings. He was eventually moved from hostel to hostel as his family frantically tried to send him money. “The stories he told me and what it’s like being treated over here were unbelievable,” Cotton says, citing the miserable stipend refugees receive as an example (right now it’s £49.18 per week, which Cotton calls “appalling”).

“The whole process was so slow, it took years,” she continues. “He wanted to end his life.” It’s a struggle Ida and Louise Cook identified as well, framing their rescue mission as “a fight against suicide as well as murder”. It is a danger that reverberates in the modern-day context: The Guardian reported last December that the suicide rate in Home Office accommodation for refugees has doubled in the last four years alone.

Throughout our conversation, Cotton reinforces how the treatment of refugees has changed very little since the 1930s. “If there was a safe passage to begin with, this story wouldn’t really exist,” Cotton notes. “This is eighty years on; what has actually changed?”

You can hear the danger in Elias’ story translating to the opening track ‘We Were Smuggling People’s Lives’. It lays out the stakes for those fleeing for their lives and the treacherous journeys they take: shrieks of wind, menacing industrial chugs and ghostly moans soundtrack the 17-minute piece, making absolutely clear that these are journeys people take out of desperation (and how tragic those journeys often end up).

There are more subliminal tributes to the Cooks’ rescuees in ‘Dolphin Square’, referencing the apartment along the Embankment where refugees first took shelter in England. She arranges the song as a polyphonic chant, each voice representing a specific person. “I want to create something quite busy. Each part was done in one take. I had characters that were people that I read about in my head, and I was thinking about them as I sang each part.”

She also enshrined their experiences into her performance of Engelchen by asking each of the refugees she spoke with to write a letter. These were read out on stage at her March 2023 performance in Sunderland, a moment she calls “incredibly moving”.

Alison Cotton by Kate Hockenhull

Cotton also got in touch with Filiz, an artist originally from Turkey, and worked with her on the day of the performance as well. “She hadn’t been able to work here yet, but she was a teacher and activist for women’s and LGBT rights,” she tells me. “But because of her work, she wasn’t allowed to work as a teacher anymore. She came over during Covid, and she said she was in a hostel with people from all over the world. Everyone’s cramped, and everyone’s passing it onto each other.”

“I found out she was a ceramicist, and I invited her to come and sell her art at the event. It was the very first time she’d sold anything in the UK, it was a really big thing. She brought her whole family and it was amazing.” Cotton is planning another performance in Wandsworth, where local poets will read out a piece relevant to the experience of refugees living in the borough.

She is visibly touched when she describes what it was like speaking to refugees for this project. “The whole thing is such a sensitive subject that I didn’t think anyone would really want to be talking about their experiences” she says. “They were really supportive, and they were really excited about parts of their lives being put into songs.

“They didn’t know the story of Ida and Louise, but they could relate to it and the experiences of those refugees. I’m so grateful for the time they gave me, and the fact they told me what must have been so difficult for them to tell me, and to trust me with all that information.”

But really, the bulk of Engelchen’s emotional power does not lie in the Cooks’ story alone; it resonates through the contemporary stories Cotton incorporates. Engelchen is epistolary, a literary genre whereby a single novel may consist entirely of letters and correspondence. Though all music, to an extent, is a form of communication, Engelchen is an unusually webbed dialogue between artist, audience, and muse; between politics, art and humanity.

Ida and Louise’s fundamental message of human compassion still echoes loud and clear. Just a few days ago in Walthamstow, <a

href="https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-68080820" target="out">400 asylum seekers were ordered to leave their hotel within a week. The Home Office charges on with their unlawful attempts to send refugees from the UK to Rwanda. Even our own Prime Minister shamefully bet £1,000 (with shining beacon of benevolence, Piers Morgan) that he could <a

href=””https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2024/feb/05/rishi-sunak-out-of-touch-bet-rwanda-plan-labour” target=”out”>deport refugees before the next election.

There is always the danger the sisters’ message will remain a distant echo. But through the voices of Ida and Louise, Elias and Filiz, and Alison, we can create a chain throughout history that binds us together, its links jingling, then clinking, then clattering with the sonorous din of human spirit until it drowns out the white noise that is nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric, until it fades into silence.