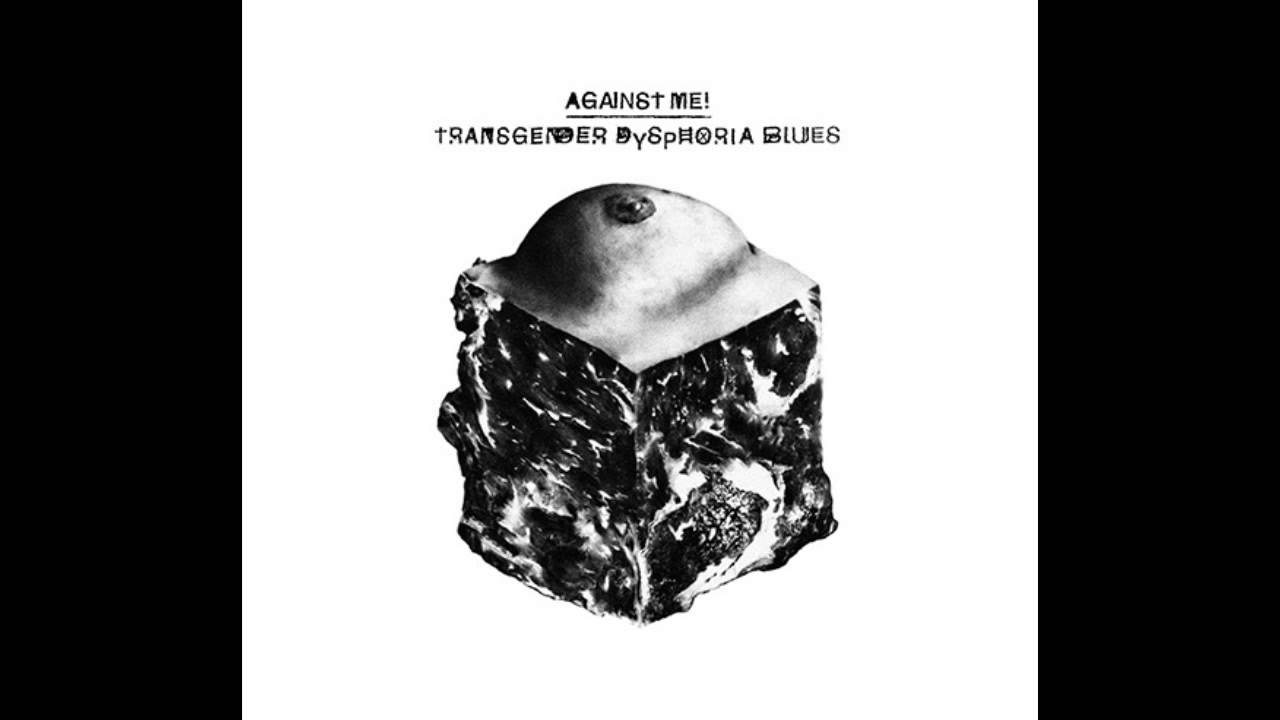

In January of this year, Against Me! released their sixth album. For a band whose trajectory – from Fat Wreck Chords to Sire Warner and back again, via cries of ‘sellout’ – has seen so much controversy, it was received relatively quietly. Its subject matter – gender dysphoria, the pain and difficulty experienced by trans* people around their assigned gender – wrong-footed some critics. Despite the long history of challenging gender norms in punk, such a directly narrative approach to transgender has not been seen before.

And it is a tough listen. The death wish, self-harm and drug use are omnipresent. Grace is open about her experiences before and during transition, detailing the daily threat of rejection, humiliation and violence, and her rage at a society that insists on brutalising trans* people. It’s not a simple story, a journey from repression to emancipation, marked by changes to a body perpetually under examination. The cover art depicts an excised breast, skin, gland, and flesh cut free, neatly squared off like nothing ever is. All of the meaning and desire and expectation that usually attach to it are not in themselves part of it. They are only what we bring to it. The body is not gender, this album argues. Listen and learn.

What was it like producing this record yourself?

Laura Jane Grace: Well the past two records we made, we were really fortunate in working with Butch Vig as producer and Billy Bush as engineer, and Billy mixed this record. The two of them are complete pros who are at the top of their game and they have made some of the greatest records of the past 20 years or more. I looked at it as the closest I’ll ever come to going to college.

But [for Transgender Dysphoria Blues] having that creative control was important. Knowing the personal subject matter that was going on with this record, I didn’t want to go into a studio that was filled with strangers and work out what I was working out, in front of them. I needed to build up walls. To cocoon myself, in a way.

I get the feeling that this record was about process, then. About learning to protect what’s important and represent yourself in telling this story, at a time when you were also learning to do that on a more personal level.

LJG: Yeah, absolutely. There’s kind of a grace period when you’re working on a record, when you’re all in the practice space, and no one can actually hear the lyrics, because the guitars are too loud. When it gets to demo stage, you’re held accountable, and you have to explain. But I knew that this was the record I was making, and this is what it focuses on, so there were choices that I made ahead of time without necessarily explaining them to the rest of the band. Like building our own studio and [releasing the album on our own label], to preserve that process.

Given that this record is about dysphoria and transition, it’s tempting to read you into every song, but actually most of them are in the second or third person, addressed to ‘you’ or ‘her’. Is this a range of characters? Or was it easier to write about something so scarily personal with a bit of distance?

LJG: Ha. Well probably 70% of the record was written before I had come out, and the other 30% afterwards. And initially, going into it, I was afraid of what I was talking about, yeah. And I tried in some ways to project into another character and disassociate myself from it, even though the lyrics were based on my life experience. A good example would be ‘Paralytic States’, which was probably the first song written for the record. That song is about a transgender person dealing with addiction and dysphoria and killing themselves in a hotel bathtub. Obviously I’m not dead in a hotel bathtub, but all the experiences of existing that way, being in that hotel room, are very much real to me, that’s a life that I’ve lived.

Actually, originally I was projecting this idea of "Oh, it’ll be a concept record about a transsexual prostitute", or something like that. But again, that was a thinly veiled attempt to defer the reality that this was me, dealing with my feelings.

You’ve spoken before about the way writing and performing encouraged you to transition.

LJG: There were certain experiences I had leading up to me making the decision to transition. One of those was a friend of mine named January Hunt, who had been a fan of the band for years, one of those people who I’d seen at shows as early as 2003 or 2004 – for whatever reason, her face stuck with me and continually over the years I would recognise her. I’d say around 2009 or 10 – and this was when I was really, really dealing with dysphoria and really kind of lost in it – I saw her and realised, "Oh, you’re transitioning." And it really… made me feel like a coward.

I don’t think anyone should feel like a coward for hesitating to transition. I’m sure other trans* people wouldn’t think of you as a coward either.

LJG: It was just like, "Oh here’s this person who’s a fan of the band, who’s followed us for years, and they’re doing something that I’m not brave enough to do."

I was just really really isolated in Florida. I’ve since moved from Florida to Chicago, but at that time, I had no community, I had no one. So now, knowing that when you go out on tour and you come to a city, you have [a community] that can support you in that way, is so important to me. As much as they may look for support from me, I’m looking for support from them. 100%.

I wanted to ask you, as a performer, about femininity. There’s a lot of stuff on the record about a frustrated desire to be seen as feminine – "You want them to see you like they see every other girl/ they just see a faggot" from the title track, or "never quite the woman that she wanted to be", from ‘Paralytic States’. I wanted to ask, what’s femininity for you? Because I think that’s a tough question for anyone.

LJG: Right. This is an interesting concept, especially for me, coming from the punk scene. The politics that attracted me to the punk scene was the idea of smashing gender roles. And in transitioning, I definitely didn’t want to go from box A to box B. I was never gonna come out looking like Betty Boop. I think what’s important for people to recognise is that there’s a whole wide world of gender variance out there.

One of the misconceptions that people often get wrong is the idea that they’ll say "after your transition", when I’m very much in transition. And I don’t have it figured out, I don’t necessarily know who the person that I am is going to be. I’m just starting on that path to discovering femininity and breaking out of male socialisation, in a lot of ways.

Making yourself up as you go along?

LJG: That’s exactly it. It’s a little abstract to explain, other than I know the way it feels. I know how I feel now compared to how I felt before, and I know the ways in which my life and mentality and the person that I am has improved since then. I’m not saying that every single trouble or worry in my life has suddenly been solved and it’s all perfect, but there are certain things that are so infinitely better, and I feel so much more comfortable and at ease with myself as a person that I’m thankful for having made the decision in so many ways, you know? But it is a path where you’re trying to figure it out and I don’t know all the answers.

I don’t think anyone does. Femme seems to be the way my body travels easiest through this society, in terms of how other people view me, but it’s not intrinsic or natural, it all feels quite performative. And it doesn’t map perfectly onto my internal gender, not by a long way.

LJG: Right. And that’s interesting, thinking about it in those terms, the way other people view you. I have the luxury of straddling this weird sense that people often times people can’t tell what they think about my gender. The way they read me is that they think I’m just some kind of rocker. Due to playing in a band and the fashion associated with it, there is already a certain amount of fluidity there.

Yeah, there’s a lot of different cultural factors that can queer your gender, actually.

LJG: Right. But it’s interesting for me now that people are trying to figure out how to read me, and I’m thinking about the way I want to be read, and not wanting to be read as male. But recognising at the same time that the majority of people do, if they don’t know me.

Lyrically, you’ve written a lot about the way that as a trans* woman, you’re held to grossly inflexible standards around gender. I’m thinking particularly of "your tells are so obvious/ shoulders too broad for a girl/ …you’ve got no cunt in your strut/ you’ve got no ass to shake", from the title track. That anyone should feel this is incredibly painful and unfair.

LJG: Tell me about it! It’s a lot of pressure, and it’s a lot of pressure doing this in the public eye, you know? It’s not healthy to feel like there’s a pressure to figure out stuff under anyone else’s timeline than your own. But also because of what I do there will be pictures and videos of me that will exist forever on the internet or in print. You kind of have to abandon yourself in that way and accept that it is what it is.

Do you see yourself as a feminist? I ask because recently these questions – about what a woman ‘is’ and whether nor not gender needs to be policed in order to protect women – have reemerged into some feminist writing and campaigning in a hugely harmful way. We’ve got our Bindels and Burchills over here, and in the US you’ve got Roseanne Barr, all abusing trans* women in the name of feminism. I was wondering how that affects women now, transitioning in the middle of this shitstorm, and in need of feminist support.

LJG: I do consider myself a feminist, yes. In regard to people like that, I mean what can you do? You have to take it like any other kind of harassment and ignore it as far as possible. I can’t afford to let the ideas of people like that rule the way I think or the way I live my life. I don’t have the luxury of doing that. Fuck Roseanne.

Fuck Roseanne for life! [laughter] How has transition affected your creative process?

LJG: It’s been liberating. Totally liberating. There were definitely songs in the past where I was dealing with these same emotions, but I didn’t feel that I could be truthful about what I was talking about, I’d often have to veil that in metaphor. Although there were some songs that were really blunt and to the point, but no one ever questioned. But now I feel like I’ve broken down a wall mentally, and that’s what you need as an artist. Pushing myself to dig deeper and deeper for whatever is the truth. For what is true to me. I don’t know if I would have arrived here without Against Me!.

The live videos of your band performing the new songs are quite moving to watch. You’re such a unit. They have your back in the best way.

LJG: For sure. When I’m on stage I feel more confident than at any other point during my day, or my life. And I get that from the audience too. It’s a totally surreal experience. You know, I reached a point of disconnect where I was standing on stage, looking out at the audience and seeing what I would assume would be, like, meathead jocks, tough guys standing in the audience, singing my words back to me, and wondering what my connection to them was or how they would judge me if they really knew who I was. And now to be back up on stage being open about who I am, and singing about the subjects I’m singing about, and see those same people singing along… Seeing a roomful of people, regardless of gender or sexuality, sing along to the line "Does God bless your transsexual heart?", it’s a great feeling.

Do they sing along to ‘Drinking with Jocks’?!

LJG: [Laughter] The record’s only out recently, but I’m sure they will! Actually that was the song that I wondered if it’ll ever get weird, you know. I don’t want the lyrics of that song to be taken out of context, for people to think that it’s alright to say some of those words unless they’re properly contextualised. It’s like that song, you know [LA punk legends] X, their song ‘Johnny Hit And Run Paulene,’ which is about rape. They eventually stopped playing that song because they weren’t sure the audience were getting it. I have that fear with some of these songs. And if it ever does get to the stage where that happens, I wouldn’t hesitate to retire the song.

But definitely now, I’m seeing much more variance in the audience. Knowing that it is a mix, looking out and seeing trans* people, a mix of genders, and cis people, singing along. I don’t want to judge them, I’m hoping they get it, and maybe they get it more than I could ever assume.

I think actually that accessibility is one of the strongest things about this record. There’s such a tension between the difficulty and uncertainty of the lyrical content, and the boldness and anthemic quality of the songwriting.

LJG: Songwriting has always been about that for me, about trying to take a negative experience and turn it into something different, liberating, empowering, you know. Singing your worst fears and feelings to a catchy melody. It’s a pretty good feeling.

On that subject, I wanted to ask you about ‘FUCKMYLIFE666’ – it’s the centrepiece of the record, and it seems really different in tone from the rest. To me it seems almost all of the record is about the risks you take in transition and what’s there to be gained by taking them, but it seems like ‘FML666’ is about what you lose.

LJG: Right. Um, and that was the last song I wrote for the record, and the one I struggled most, lyrically, to get right, because I was trying to say a very specific thing. With the record being 70% pre-coming out and 30% after, this was very much an after song.

It’s about realising the way that already, this is affecting my relationships, and the way it’s changing them, and, um. The worry of knowing that you are who you’ve always been, but other people are now seeing you in a different way, and worrying about the people you love, whether they’re going to continue to love you in the same way, or you know, the person that you’re attracted to, whether they’re going to continue to be attracted to you, and… you know, it’s terrifying and there’ve been a lot of changes in my life that are heartbreaking, that have been a part of my transition.

It does sound heartbreaking. I’m wishing for you to be loved and desired in exactly the way that you need to be.

LJG: Thank you, Petra.

Of course.

LJG: You know that worry over whether or not people are going to love you and accept you, once you do show that part of yourself – the worry over whether or not a god would even love you. Those were all fears that were very real to me. But accepting myself and leading an authentic existence, ultimately, was more important to me than any of that.

Transgender Dysphoria Blues is available now on Total Treble records