To someone who believes in rebel music, the coincidence of the 30-year anniversary of Adrian Sherwood’s label On-U Sound with the populist political uprisings of 2011 could seem almost astrological – like a shift in the alignment of the stars causing an inevitable surge in energies.

Adrian Sherwood has a phenomenal CV. Inspired by reggae to teach himself sound engineering in his teens, Sherwood has forged a career that has epitomised the inter-racial trajectory of dub through England, from putting UK production on the map, right through the mutually inspiring transfusion of reggae and punk, acid house and experimental hip hop. He has collaborated with the likes of Prince Far I, Lee Scratch Perry (including the seminal album Time Boom X Di Devil Dead), Ari Up, PiL, Mark Stewart, Depeche Mode, Primal Scream and Asian Dub Foundation. In a logical progression he has recently commissioned remixes from and toured with dubstep producers Mala (Digital Mystikz) and Kode 9. To celebrate of 30 years of On-U, Sherwood is releasing a series of reissues of key releases from what has been an awesomely prolific label. When I met him, I was starstruck not simply by this list of credits and the man’s talent, but a sense he inspires, partly from what is already held in my own imagination, of music’s unique power to mobilise.

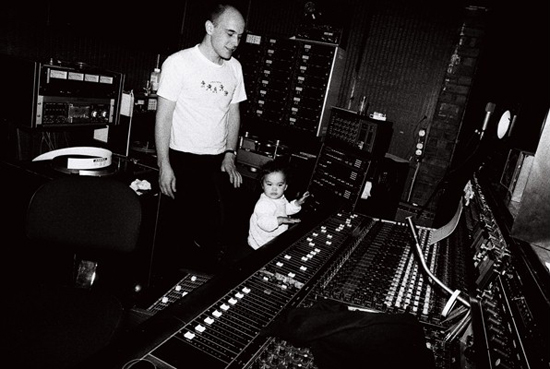

So you’ve got four albums – or three re-releases and one new release coming out in the next few weeks. Can you run through them?

Adrian Sherwood: Well, previously what would happen would be there would be record shops and people would go there and browse through the shops, and we’d have our own little section in the shop – you know, the cool shop – and that’s how traditionally things would be. But now obviously it’s changed so much. People don’t sit hours and hours looking through records and things; we’ve moved to a new era. So I’ve got a situation where I want the physical copies to be available again.

So, we’re gonna do 12 re-release this year. Every three months we’re gonna re-release three albums. There’s Off The Beaten Track, which is a classic African Head Charge album, plus the first African Head Charge album there’s been for years, which is called Voodoo Of The Godsend, which I’m happy with. And it’s gonna happen throughout the year where there’s a new release with each batch of releases. So, 12 re-releases and four new ones…

Can you just take me through the first three re-releases?

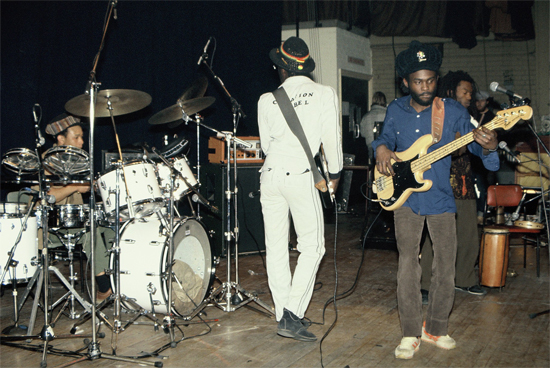

AS: The first re-releases are the first New Age Steppers [eponymous] album, which is 30 years old this year; African Head Charge’s Off The Beaten Track because that coincides with the release of the new album; and thirdly, Starship Africa by Creation Rebel, which is a classic dub album.

Creation Rebel actually predates On-U. That was recorded in 1979 when I was 20 or something, and it was one of the second records I ever made. It didn’t get released until 1980, on 4D Rhythms, which was before On-U. And I released it as part of the new batch when I started the On-U Sound label. It started as a studio thing where I had a lot of great musicians: Tony Henry, Misty in Roots, Clifton Morrison who does Jazz Jamaica, Crucial Tony who was Ruff Cut… they were some very important British reggae musicians, and they were all involved in the original Creation Rebel, but we were all teenagers at the time, or early 20s.

Creation Rebel live

There’s a whole story about how we hooked up. I started working with Jamaican musicians from my mid teens, like 14 or 15, and I grew up knowing loads of people and got introduced to musicians, so I made my first record where I said I’d come to the studio and play. And I made up the record humming basslines and what they called building rhythms with these players. On tape, to release it on vinyl. That was before cassette as well.

So why did you re-release it on On-U? Why was On-U able to reach a wider audience?

AS: Well, 4D Rhythms only had one release. Before that I had a label called Hit Run, and when I was 17 I was involved in a label called Carib Gems, but by the time On-U started I owned a few things. I owned Cry Tuff Dub Encouter Series, which is Prince Far I dub albums – Volume One and Three I owned, although I worked on all of them. And I’d already released Dub From Creation, Rebel Vibrations and Starship Africa by the beginning of 1981. I re-released Starship Africa because lots of people were citing it as being a very influential record, because it was all mixed backwards and it was quite trippy. It was one of the early releases on On-U. I made it available again, as one of my productions, as all the releases on the label are my productions.

So when you set up On-U you had a better network for your label?

AS: Yes.

Can you explain what mixing backwards is?

AS: Well, if you take something that’s playing forwards and then you turn it over so it’s playing backwards – if you add a like a reverb to it and go ‘kowww kowww’ on the snare, if you play it back it would go ‘shhhhok shhhhok’, so the effects will play backwards. So that’s putting delays on everything, and just randomly bringing things in and out, dubbing them out – bassline out, in, drums out, chops, jang jang jang juang jang, but played backwards. Then we’d put it onto a tape and play it forwards, but the effects were sucking and playing backwards.

Were you the first person to do that?

AS: Yeah, I think I was one of the first people that did it. I can’t hear many records before that that did it. That was 78, 79. I think in the 60s a lot of the hippies in the psychedelic movement, but not out of the reggae era, were doing that: backward tapes and taking loads of LSD and making weird records.

OK. What about African Head Charge?

AS: Well, African Head Charge again was a studio name I had to start with, and it evolved into a band about eight years later. That started out again I read an interview in a newspaper where Brian Eno talked about he’d made an album called My Life In the Bush Of Ghosts with another musician – that Talking Heads fellow [David Byrne] – and he said ‘I had a vision of a psychedelic Africa’. And I thought, ‘Oh, that’s pretentious’.

But then I thought about it, and thought ‘No, what a good idea! Make really trippy African dub’. From that day to this day, people really are scared of African music. You don’t hear loads of mental African drums in conjunction with big fat b-lines, do you? And I think it sounds great, with the hi-life guitars. So I entered that area and I used Bonjo, who’d been in Creation Rebel and is a great percussionist. I built the thing around his percussion playing and the idea of making some really spaced out African dub. That was the idea of it.

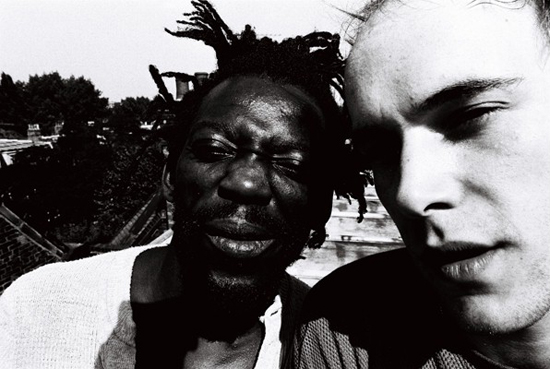

Adrian Sherwood with Bonjo from African Head Charge

Where was the studio?

AS: That studio was off Clerkenwell Road, on Bury Street. It was a studio underneath the ground. We were just in there chainsmoking; it was really unhealthy. A dungeon, really. Eno’s album was called My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, so I called mine My Life In A Hole Under The Ground. And he kept talking about vision of a psychedelic Africa, so we called it African Head Charge. It wasn’t really taking the piss out of Eno. I think he thought we were laughing at him – it was having a laugh, but respectively.

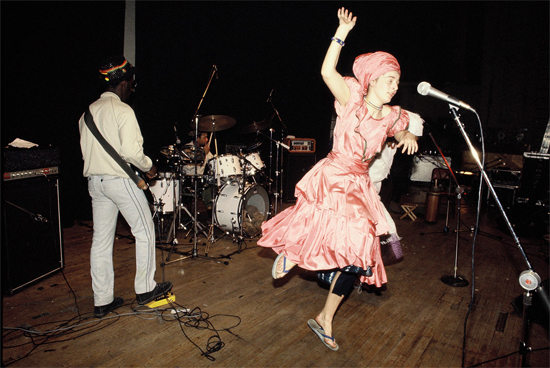

And New Age Steppers… how did their formation come about?

AS: In 1979 we got invited to do a tour with The Slits and Don Cherry, the jazz trumpet player, and he had a band called Happy House that was Lou Reed’s backing band working with him. The Slits had been coming to our gigs – Prince Far I and Creation Rebel gigs – in 77-78, and then when they had their first tour they invited us to be on it. So on that tour I became friends with Ari, and I’m still friends to this day with Tessa and that. And we did some recordings, Ari and myself and some different musicians from Creation Rebel, PiL, The Raincoats, Steve Beresford – lots of different interesting people that you’d never expect to be on one record, from reggae backgrounds, funk, jazz and punk backgrounds. And we made that album. The interesting thing about it was being made in 1980 and coming out in 1981, it was the first On-U album… it did sum up that period, like when people were curious about each other’s things, and it was the real players at the time.

New Age Steppers live

When you recorded it had you rehearsed it, or was it quite spontaneous?

AS: It was quite spontaneous, because we had the reference point on the cover versions: ‘Fade Away’ [a cover of a Junior Byles song], and ‘Love Forever’ [a cover of a Bim Sherman song]. Mark Stewart had already written his song ‘High Ideas And Crazy Dreams’, so we knew where we were going on them, and the others were built off basslines, as kind of part-jam dub. And Viv Goldman had private armies – she was my friend so I took her rhythm and built it in, so it fitted with the other tracks. So it was a whole group of mates and people who were mingling together; it was basically Ari and my love for the reggae, and recording something around it. That was Bury Street again, and Free Range Studio, and a couple of other places.

Were these studios that you rented?

AS: Yeah. It’s funny, it was more expensive to rent a studio then as it is now. Or as expensive, in real terms. It was quite expensive – comparatively, massively expensive.

So you had to be spontaneous.

AS: Well, you couldn’t mess around. At any given time I was owing a studio maybe 10 thousand quid, and you could buy a house in East London for 20 thousand quid.

Why didn’t you just buy a house and turn it into a studio?

AS: We couldn’t do it in those days. Tt was really funny… you gotta bear in mind how things are: TV ended at 11 o’clock at night, no shops open on a Sunday. It was a different world. People don’t remember how things were. There was lots of racial tension. People take it for granted now that things are what they are now, but the average wages was maybe £50 a week, and I was spending that on two hours’ studio time, or an hour and a half studio time. Now, it seems naïve to you or whatever, [but] for us it was brutally harsh that if you made a few mistakes you could be in a lot of trouble, financing it ourselves. No-one was helping us. I was selling records out the back of a car.

So did you bring your own equipment to the studio?

AS: I didn’t have anything. I didn’t own anything. I just used whatever was available to me.

So you must have learned to be quite…

AS: I learned doing live sound first, doing gigs with Prince Far I. And [after] doing live sound, you know when you go in the studio how you want the picture to sound and you’re not scared. So I think anybody who’s doing music should start with live work so they get their head around how things sound.

Adrian Sherwood with Ari Up

I think not many people do that any more. Most people just start at home with their laptop.

AS: Yeah, they spend their whole life at home looking at a screen, a lot of people. I try and tell my kids they don’t understand just how mad it has become. You used to license in clubs used to have to close at 2 o’clock, pubs closed at 10.30, they weren’t open at lunchtime. People felt bored, like there was nothing for them, so the whole punk movement came along, and reggae. It felt like it was a breath of fresh air to challenge people.

Can you go back in your head and take me through why you started the label, and whether you were excited or nervous, and what you hoped to get out of it?

AS: I don’t think you think about getting something out of something so much. What I’d done up to that time from the age of 17 to then – which was twenty two or something – was run labels. I had a distribution company, but I’d run labels and done my first production. So I’d suddenly got the taste for being involved in the creative process, and once you’ve got involved in that it’s like an addiction. Once you’ve started doing it you really wanna keep going, because it really is addictive. There’s no other word for it, once you’ve got that interactive creative thing going on. But in those days you could see a future in it much clearer than you can now, so it was much easier and much more fun for me in my day, I think. It was like virgin territory; you were going somewhere that was innocent. It had a naïvete about it. Now, it’s kind of ‘Okay, I’ll enter that arena, and I’ll use those reference points’. There was a charm thing that has been eroded by the speed of communications now.

If you’ve got a nice little idea and you’re living in one part of the world, before you know it, it goes into the digital domain and someone’s listening to that on the other side of the world, and will take the essence of what you’re trying to develop before it’s even had a chance to flower. We could do things before and you wouldn’t hear things for years or months, and it would suddenly be ‘Wow have you heard what’s popped up out of Iceland – it’s called KUKL’, which became The Sugarcubes, and then it became Bjork. It was mad. And now everyone uses that reference point of her, so it’s not the best reference point, but I knew her from that time because we used to use the same studio.

Now, everything’s exposed too quickly, before it’s had a chance to grow. That’s not criticising now – it’s just how it is. We used to have a thing where you’d have to hang out at all-night music parties – reggae clubs were house parties – because everybody else was tucked up and there was nowhere to go. There weren’t all night clubs, there wasn’t banging massive PAs. The massive PAs were amongst us, we were the first people… I say ‘we’, I mean the reggae community and people who were into big noise pioneering 30k rigs, in front of like five hundred people. Before it used to be a wanky PA just playing rock & roll in mono by someone who had no understanding of bass. And reggae educated people by having a super sub on the soundsystems, [and got us] to where we are now, when even pop records like Britney Spears have got amazing super bass on them.

A lot of what you did – and with you just saying before that the racial atmosphere was a lot more tense in the early 80s, and you were mixing up punk and reggae and black and white artists – had an inherently political aspect. Did you see what you were doing as political?

AS: I think that reggae was carrying a political message because they were talking about sufferation, Garveyism, the back to African movement, pan-Africanism, the rasta thing, which was about the improvement of black people and the proudness of being black and the need for revolution. And over here you had the punk movement which was like ‘I’m so bloody bored, can’t we do what Guy Fawkes failed to do – blow up the place’… disenchanted white youth. And they were all kids who went to school together, and a lot of white kids were into reggae so it brought it all together. And on our front I had Mark Stewart, who was very politicised, and he had made The Pop Group albums, saying we tolerate mass murder, we’re all prostitutes etc. By the time I was working with him and we were doing all his records which were all coming through On-U, and Tackhead after that… all that stuff was like news on the beat, as we called it. We were cutting up information, and Mark was our Gysin or Burroughs or something.

But I was brought up listening to the news in England, and you think ‘Oh those poor Israelis how they’re suffering’ and you never heard anything about what they did to Palestine, or what went on. You were depoliticised from quite an early age in this country. But in the 70s there were loads of movements for workers’ rights, the political situation… it was all put much more in your face, and it’s only now I think we went through a gap for 20 years where I think people are comfortable with making money, they bought into the whole Thatcher thing. So I think with On-U, we were attempting to be as political as possible. I had to learn things – I learned lots of things off people about what really goes on. I didn’t know the txtent of what goes on in the Middle East, about American Foreign Policy, the destabilising of governments like Nicaragua. I had to be taught that myself. I wasn’t taught that by my parents or the school system.

So you learned that from Mark?

AS: Yeah, Mark and other semi-intelligent people. And I learned that from reading, and learning, as life’s gone on.

So you were effectively being politicised through the music?

AS: Yeah. I mean, I’d got that in my spirit from the reggae people as I said to you before, and then we started getting the politics of trade unionism, the world stage, what was going on, what they now call the conspiracies and stuff. My daughter come to me the other day and she said ‘I’m really scared of the illuminati!’ [Laughs]. But it was interesting, because there was years and years, and there was very little political activity because everyone was so greedy, buying into the idea of we can have it all.

Adrian Sherwood with Deadly Headley

Do you think there has been a loss of quality at all in sound production?

AS: Well, the only difference is that because now you’ve got digital, you’re missing a couple of frequencies and people will say to you vinyl sounds bigger. And if you play the vinyl and you put the same record on on a CD now, it will sound great but a little bit tinier. And we used to spend hours trying to make the dynamics super huge, but now people are listening to tunes that are massively compressed on their phone, so it leaps out of the phone, but if you played one of the tunes I’ve done on the phone it might sound really tiny. But if you put it on on the stereo, it might sound really panoramic, whereas the tune you played on the phone would sound like here [points to space off the floor above the ground] so it’s rising above the shagpile carpets. What we did was like bass immersed underneath the floor. So, I’m not attacking anything now, but analogue has a warmth about it that’s not present in digital recording. I do mainly digital recordings but emulate analogue sounds by using analogue effects and flying it back over the digital thing just to make it warm – or try to.

And I suppose technology’s evolving to do that better than before isn’t it?

AS: The technology now… everything’s available as a plug-in. So it’s kind of… it’s like people don’t want to fill up the whole of one room with a record collection. If you put a vinyl collection in here you could fit everything stored in this room – half a tonne of vinyl – on one bloody MP3 player. And young people would say ‘Why have you got all that weird stuff? What’s that?’.

It’s like we used to laugh at 78s but we were playing 45s – it’s not much difference. I’m not pining for times gone by. It’s moved on, but the thing is, I know certain things that other people don’t know and I use that to my advantage, and I’ve got those happy memories. But I can see why you can never go back to tape. It was probably ecologically a crap idea anyway; it was expensive for one, and looking at it now, the digital recording thing is probably just great. There used to be hours of slow rewinding, you always had to rewind the thing to drop in, but now it’s just instant, and that’s good. But I’m glad I went through what I did, because I understand things that other people haven’t quite got their head round.

You’ve done shows with Mala from Digital Mystikz and Kode 9…what similarities do you see between them and you?

AS: Well, Kode 9’s a bit more techno-y than Mala for example. Mala’s a slightly different vibe, a bit more rootsy. Steve’s [Kode 9] got a very modernistic view of things. But they both understand, that’s the bottom line. Other people do things and they don’t understand the essence of what makes it really beautiful and great, and both of them have got a good knowledge of the essence of what’s proper.

What’s that?

AS: Well, the understanding of space, the understanding of tone, and healthy tension and things like that. You have to understand those things if you’re trying to make something that captivates someone who’s listening.

Tension in the music?

AS: Yeah. Something that grips you. Not an unpleasant tension, something that holds you.

What about differences, between them and you?

AS: Well, that’s called imagination and flair, isn’t it? I don’t think they are things that you can just analyse. Mala, for example, has got his sound; you can hear his work. He’s got a style. That’s what I say to people who are starting up: try and get your own sound. Similar with Steve, he’s developed one, and Burial, he’s got his own combination of things that he does, and you’ll hear it and be like ‘Oh that sounds like Burial’, or ‘That sounds like Kode 9’. That’s the sign of a good producer or artist, that they’ve got their sound. Or a good singer – [or] great singers – you can hear ‘Oh, that’s Gregory Isaacs’ or ‘That’s Rod Stewart’. That’s the same with good producers; they’ve got a sound you can identify. All the ones I like have, anyway.

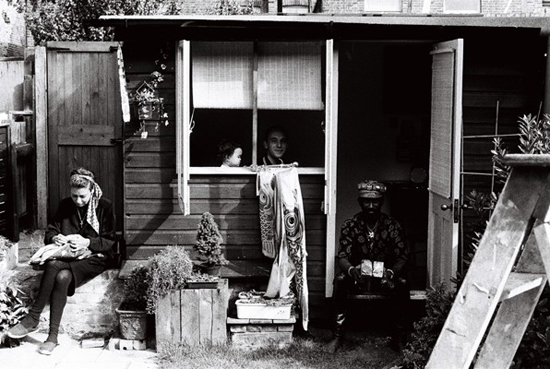

Adrian Sherwood’s garden shed, Annie Anxiety and Lee Scratch Perry. Annie lived in the shed.

The early 80s are notorious in people’s imaginations – I was just a kid then but I have an idea we have of it now, through popular culture like what you were doing and The Specials and all that music. We’re also in quite tense times now. Do you see parallels with what’s going on now, with the cutbacks and the protest movement?

AS: Well, when I was young, it was horrible. There was lots of such negative things: racist shit, ignorance. Lots of good things have happened to put us where we are now. There are lots of good things now that we didn’t have then. But everyone in those days had work – or not work, but the chance of work or the chance to drop out, and it was a lot cheaper to live in relative terms. All the things you needed to have to make life seem worth living…

Now it’s very hard to get any work for anybody, so you went through a period in the last 20 years which people thought was never gonna end: ‘Make money, make money, be successful’. And that all came from Thatcher when she destroyed the Trade Unions. They sold off things that the country already owned to people, trying to turn people into little shareholders, house holders, and the left wing politics is all so in the centre now. But suddenly people have realised: ‘Hang on, this is insane – we’re in danger of having a really crap life, a life barely worth living. We’re gonna be covered in debt put on us by these private companies who are controlling our money supply’.

Controlled by debt, where where only children of the rich can afford to do music or dance or drama or something. It’s gonna be very grim for everybody, so people are like ‘Hang on, no. Why should we have to pay 30 grand a year to pay for our kids to go to University or whatever?’ So there’s now gonna be a lot more politicised music, I would imagine.

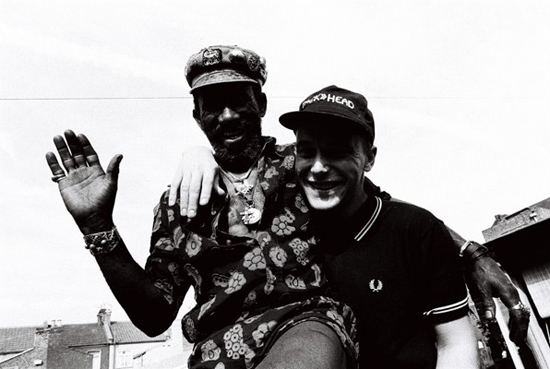

Adrian Sherwood with Lee Scratch Perry

People should be saying, who is actually printing our money? How can America owe 14 trillion dollars? Who are they supposed to owe it to? How come half of America is run by joint Israeli passport holders? What’s going on? Why are all these countries so angry? Why has the CIA destabilised the whole of South America and the whole of the Middle East? And now you’re seeing political uprisings from Tunisia to Libya to all over the place in the Arab world; you’ve got lots of people all over South America who feel just the same way where puppet regimes are put in, and our own country here which has been running things for donkeys years… if people get their heads round what’s going on, I think it’s gonna be quite interesting political times, before they plunge us into some other fucking war or something.

So do you think that music will inevitably respond to that?

AS: It tends to reflect what’s going on, doesn’t it? Jamaican stuff reflected it for years. But now they’ve even killed the record industry. Imagine if they shot the satellites out the sky. What would go on then?

Music to me feels generally more politically detached now.

AS: Yeah, well I think it’s gonna have to come back. We’re gonna have to get more on it again. At some stage people are gonna get very pissed off again. I hope so.