The Second World War introduced a generation to the world of electronic sound. For Delia Derbyshire it was the bombing of her home town, Coventry. The wail of air raid sirens, the crashing cacophany of aerial bombardment. Electronic howls and screams that would turn up later on such pieces as Blue Veils and Golden Sands and the Delian Mode. For Tristram Cary it was working as a radar operator in the navy, hearing rumours about a new technology developed in Germany but never before seen in Britain – the tape recorder. Coming from a musical background (his mother was a cellist and apparently a fine singer of romantic liede), the possibility of editing tape, cutting and pasting, immediately suggested to Cary the possibility of combining instrumental music with recorded sounds, such as that of a thunderstorm, or a bee landing on a flower.

Returning home after the War, his naval gratuity of fifty pounds bought Cary a disc lathe, the cost of a tape machine still way out of reach, and he began cutting his own records and playing around with the sounds therein. It was only several years later, when his old school friends, the singing duo Flanders and Swann, came back from touring Paris, that Cary discovered Pierre Schaeffer had being doing exactly the same thing at the French national broadcaster, the RTF. It was Schaeffer who had announced the liberation of Paris over the radio, and he’d spent his time since making a series of studies in what he was calling musique concrète. Cary’s inventions, however, were entirely his own, developed wholly independently. Before long he could lay claim to Britain’s very first electronic music studio, and if the initial impetus came from the military, so too did a great deal of the equipment, pieced together as it was from war surplus oscillators and transistors.

It is not only the War and its effects that links Tristram Cary to Delia Derbyshire. Though she is justly celebrated for her realisation of Ron Grainer’s theme for Dr Who, it was Cary who provided the initial musical accompaniment to the Doctor’s most notorious enemies. In December 1963, as the Warren Commission began its investigation, the fifth episode of the sci-fi series’s very first season saw the Tardis landing in a petrified forest on a dead planet, the aftermath of a nuclear war. Survival had forced the inhabitants to encase themselves in metal – Daleks, and the electronic scream which punctuates their entrance is just a part of Cary’s thrilling synthetic score. Every moment sounds like the future, scattered fragments of a Kompakt Pop Ambient compilation sucked forty years back in time. When Derbyshire set about redesigning the theme tune, ten years later, it was on an EMS synthesizer, co-designed by Tristram Cary.

By that time an established composer for film (notably The Ladykillers) and television, Tristram Cary became the first director of Peter Zinoviev’s Electronic Music Studios upon its foundation in 1969. EMS was the birthplace of the VCS-3, the very first British-designed synthesizer, used by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, White Noise, Pink Floyd, Brian Eno, Pete Townsend, Hawkwind, Gong, Klaus Schulze, Georgio Moroder, and Kraftwerk, among many others. Many of the staff at EMS would go on to work at Pierre Boulez’s IRCAM institute in Paris, and the company went bust in 1979 (although in 1995, Robin Wood, EMS’s sales director in the 70s, acquired the rights to the company, and is now manufacturing and selling VCS-3s again). Cary left EMS in 1972, to take up an academic post in Adelaide, giving him more time to concentrate on his own concert music.

Most of the music on the new release from Trunk Records comes from the period shortly before the departure for Australia. Simultaneous to his work for the BBC and EMS, Cary was commissioned to write music for a number of corporate and commercial films. Perhaps the most striking material though, comes from his music for the British and Canadian exhibits at Expo ’67. Originally intended to take place in Moscow, but moved to Montreal at the last minute due to Soviet concerns about the potentially damaging influence of thousands of corrupt westerners, the 1967 International and Universal Exposition featured pavilions from over sixty different continents across five continents. These included a Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome for the American pavilion, and within the French, a light and sound installation by Iannis Xenakis called a Polytope.

From their birth at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851, universal expositions, or World’s Fairs, have exhibited triumphant displays of the world’s artisitic and technological achievements, having in turn a significant impact on cultural futures. It was at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, with the unveiling of the Eiffel Tower, that Debussy first heard a Javanese Gamelan orchestra. At the Brussels Expo in 1958, Milos Forman conceived the first film of the Czech New Wave and Daphne Oram was inspired to leave the BBC Radiophonic Workshop to set up her own studio and develop her Oramics machine. A replica of 1967’s geodesic dome now stands at the centre of Disney’s Epcot centre in Florida, itself similarly divided into nationally-themed areas like a kind of permanent World’s Fair.

Expo 67’s over-arching theme was "Man and his World," and, like Epcot, ideas about the future of human habitation were at the centre of this notion. Architect Moshe Safdie dsigned Habitat ’67 as a prototype housing estate, constructed out of concrete blocks assembled in much the same ‘modular’ fashion as were contemporary synthesizers, like the Moog. Amongst other Canadian exhibits was a multi-screen film projection by former Norman McClaren associate, George Dunning (who a year later would decamp for Britain to make Yellow Submarine with the Beatles). Dunning’s film, called Shaped for Living was a surrealistic collage of clips and animations exploring aspects of product design and ergonomics, with musical accompaniment by Tristram Cary that followed the same manically eclectic path as Carl Stalling’s music for the Road Runner cartoons, or Raymond Scott’s Manhattan Research Labs material.

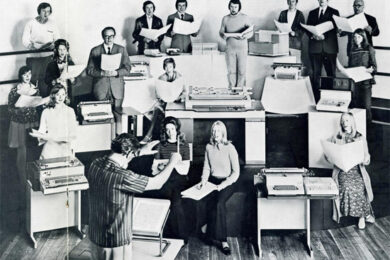

Cary also provided all the music for the Industrial Britain section of the British Pavilion, an eerie electronic whorl, anticipating such dystopian visions as the music created by Jerry Goldsmith or Slava Tsukerman for such films as Logan’s Run and Liquid Sky. His music for the escalators within the pavilion consisted of six different oscillators whose levels were controlled by the movement of passers-by. International expositions continue to this day – this year’s is held in Shanghai. However, whereas the ‘pin cushion’ architecture of the British pavilion has been attracting considerable attention, according to the website of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, its musical accompaniment will consist of "orchestras or jazz bands" – promoting a very different idea of British music to the kind of futuristic soundscapes and experimental sonic art provided by Cary forty-three years ago.

The phrase, "A new world every heartbeat" is taken from the novel, The Horse’s Mouth, by Tristram’s father, Joyce Cary. Though by all accounts, Cary Jr. could scarcely be further temperamentally from the perenially self-destructive Gulley Jimson, hero of Joyce Cary’s First Trilogy, the phrase nonetheless carries some of the utopian spirit of the sounds created by the younger man. Whether soundtracking an alien invasion or a domestic idyll, Tristram Cary’s creative powers seemed to be in a constant fast forward, forever beckoning the future closer, forcing it to realise itself in the now. If finally, it is, as Trunk attest, "time for Tristram Cary", it is because finally the rest of the world is starting to catch up with a man forever ahead of his own time.