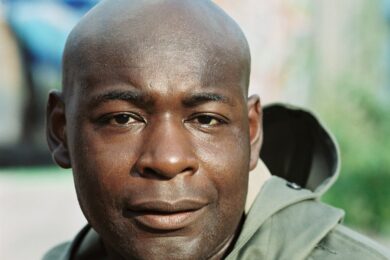

A potted history of UK dance music wouldn’t be complete without mention of A Guy Called Gerald. He may hide behind a moniker in equal parts unassuming and unwieldy, but his music is far from either.

Growing up in Manchester in the 80s – through the invasion of imported electro and then house sounds from the US – the man born Gerald Simpson made his first splash on the burgeoning acid house scene with the ubiquitous ‘Voodoo Ray’. From there his rise was meteoric, taking in major label success, two seminal jungle albums (1993’s 28 Gun Bad Boy and 1995’s Black Secret Technology), and more recent activities in house and techno from his current Berlin base. His is a career that’s spanned over two decades, all the while resisting the honeytrap of formula and self-parody which seduces so many figurehead producers.

A fine example of Gerald’s independent spirit would be his recent decision to delve back into his musical adolescence, putting together a ‘True School’ set of the sounds which dominated pre-acid house, pre-Hacienda Manchester. This music – mostly US (or US-inspired) electro and proto-house – has huge resonance with current musical trends, and is ripe for re-evaluation; and who better to introduce it to new audiences than someone who was there at the time, as a dancer and avid fan?

The Quietus had a chat with Gerald after his set to a packed venue at the Bloc Weekender, under the vast marquee canopy of Butlins in Minehead. With helpful interjections from Gerald’s Manager, Megan, and Bloc Press Officer Nancy (as well as the odd passerby), Gerald spoke about his musical roots, his optimism in the internet age, and various run-ins with major labels, fellow artists and a manager or two.

I want to ask about the ‘True School’ set you’ve just played. What made you decide to go back and start playing those tunes again?

Gerald Simpson: I’ve been listening to some of the newer stuff around recently, and there’s loads of older influences in there. A lot of my friends in Berlin, really young friends, they’re producers but they don’t know any of the old music. I thought it’d be great if they knew where it came from. So I started listening back to some of that stuff and playing it. Some of it’s got to be a little bit sped up and the quality isn’t always that good – there could be some remastering on a lot of it – and I know a lot of the producers and writers of the old stuff have disappeared now. But I thought it’d be nice to give a little bit of the roots of the music – go back to the early 80s, where I found the music.

I got interested in it around 81 or 82. I was going out dancing, and they started playing this electro-ey stuff – ‘Planet Rock’, Nucleus, that kind of vibe. That blew us away back then – dancing-wise it was perfect. Before that we were listening to jazz, funk and soul, where the music was all played live. But this stuff – you know exactly where the beat’s gonna come, so dancing-wise you can experiment a bit more, leave a few beats out, come back in somewhere else, and it’s spot on. We had loads of dance crews going around in Manchester. Actually there’s a tune I didn’t play today but I should have played, by this breakdance crew in 84 called Broken Glass. They were pretty famous in Manchester, and then they did a record – it was the biggest thing since sliced bread!

[At this point a man wanders past and interrupts Gerald to congratulate him on his set]

Thank you! Thanks. But yeah, Broken Glass was a boost for me, it was like ‘Wow, if they can make a record and they’re from Manchester…’ After I heard that, I was trying to get a drum machine – it took me until about ’86 to get one! [laughs]

So at first this scene was based on imported US records. How long did it take for people to start taking the sound and making their own records in Manchester?

GS: Quite a while. The next thing I heard after Broken Glass, house-wise, in Manchester was this group – they used to be called Quando Quango and then they changed their name, and in the end they became M People with Mike Pickering. They did a track called ‘Cariño’ [under the name T-Coy, with Simon Topping and Ritchie Close]. It could have fit in with any of the American stuff. After that I started sending my stuff into the radio – I had a drum machine and a [Roland TB-]303 by then – and they started playing it.

How hard was it to accumulate production gear then?

GS: I used to spend all my weekends not at the record shop but at the music shop – the synth shop. I’d play around with these synths. I realised, at some point, that I could afford this 808 drum machine. I think it was like 180 quid. I got this job at Macdonalds, and worked out that if I did this many shifts, I could get it eventually. So I put some money down on it, not realising that it was the end of everything for me – because once you had the drum machine, you needed the keyboard; once you got the keyboard, you needed this bass machine – then a mixer, then effects. I had to keep working at Macdonalds for a couple of years! Actually, I remember when I was leaving there, I wrote them a letter saying [haughtily] ‘They played my music on the radio so I must leave you know’ [laughs].

How long did it take you get to a point where you could live off your music?

GS: I think I was really lucky. I did this stuff that used to be demo’ed on the radio – under the name Jackmaster G – which started to get played nearly every week. I took it more seriously then, and made the attic at my mum’s house into a recording studio. I’d have all these people from my estate coming round to do some recording. And these guys came round one day and said ‘this small label in Liverpool [Rham! Records] want to put some of your stuff out’. A couple of weeks later they gave us some studio time, and I did 4 or 5 tracks – there was ‘Blow Your House Down’, ‘Voodoo Ray’…a few others. They pressed up 500, and from there I did a little deal with them where I’d get studio equipment and some money on the side.

I knew a little bit about the publishing side of things too – just the basics. This label was trying to get into publishing my stuff, but in the end we agreed that they’d have the rights for a year, then I’d get it back. So they really pushed my stuff, and after about 6 months I was in New York, Frankie Knuckles had done a remix of my tune, all this kind of stuff. From there I actually wanted to sign with Factory – Tony Wilson, God rest his soul, was going to start a Factory dance – but at the time I was in a dispute with this other group he was going to sign, and my management wanted me to be on a London label. So I was gutted in the end that It didn’t work out with Tony.

Nancy: Who was the other band?

GS: 808 State. At about the same time I was doing ‘Voodoo Ray’, I did some recording with them. But I didn’t realise they were trying to get a recording deal, and when they got one I was like ‘well I’ve got my own stuff going on, so I can’t actually be involved with this’. Which also meant that anything we’d recorded together, they couldn’t put out. And at the same time, I didn’t have as much power as them – they had a record shop and all this – so I decided not to tell them about my other stuff, just say I couldn’t do it, and they wanted to know why. To cut a long story short, we got into a bit of a tussle, it took a few years to sort out, but we sorted it in the end.

In Detroit in the early days of techno, there were famously a lot of cases of artists who weren’t educated on the business side of things getting exploited by their labels or managers. Would you say it was a bit like that in Manchester back then? Or were artists generally quite savvy?

GS: Well there were a few bands in Manchester at the time – there was this band called Sweet Sensation who had this track called ‘Sad Sweet Dreamer’ – and because it was so local, everyone knew what everyone was doing. So you followed these bands, and thought ‘wow, they’re gonna be as big as Simply Red!’ [laughs]. And then they weren’t, and you wondered why not – and you’d realise there was some management thing, or somebody took the money before they got it. After that, you’d think ‘OK, I’ve got to get a bit cautious about this’. But it was always happening – even with ‘Voodoo Ray’, for a quick second there was a bit of hassle with a guy who wanted to be both the manager and the label. When I told him that that would cause a conflict of interest, he just disappeared! After that I realised I had to start managing myself for a while.

The whole goal during this time wasn’t ‘I want to make loads of money’. I just needed a recording studio. I was getting so frustrated, I wanted to be able to record more; all the time. At first I was booking studios down in London, going to the Roundhouse, but I figured out that it was costing like a thousand pounds a week.

Megan: A day!

GS: A thousand a day, sorry! And it’s a lot of money. By now I’d signed this thing with Sony, and said to them ‘I’m spending all this money, why don’t I use it to get my own stuff and do it from home’, and someone signed it off. I think they forgot about it, because half a year later I gave them a finished album and they were like ‘how’d you do that?’. Turns out they wanted me to record in their studio, because that way they’d own the tapes. The way they work is to get their artists paying them to use their studios, always keeping the artists in the red. You know, ‘go and buy a porsche and crash it!’. The last thing they want is the artist being into the music and recording at their own studio, and then giving them the final thing just before the mastering process.

Would you say then that your experience with the major labels wasn’t good?

GS: Well it was educational. By the end, I was kind of trying to tell them about the mp3 thing. The last argument I had with them before I had to leave was, we started to do these dubplates to give to Grooverider and Fabio, all these guys. Everyone was doing dubplates for promo, and I couldn’t because in my contract it said that I wasn’t allowed to give a digital recording of any unreleased music to anyone. I tried to argue the deal with them, saying ‘these guys have probably got more coverage on Cool fm then there is on Radio 1 for this kind of music, it’d work out in my favour as a marketing thing’. But in the end the label couldn’t do it. So I started my own little label called Juicebox, and fucked ’em off.

Is artistic independence important to you then?

GS: Yeah, I think it is. For any artist who’s truly into the music, it is. For me, the money isn’t the important thing. I know it sounds really cheesy. But it’s about having a system to get the music out there. And in them days we didn’t have mp3s, any of that kind of stuff. To do a digital recording you needed a lot of money – and I wanted to be cutting edge the whole time. So we were pushing for something that would be recognised in the future; that was the goal, to push the music forward.

Your music has gone through several distinct phases – from acid house, through jungle and into the house and techno you’ve been doing in the past 10 years. Did you ever feel pressure to be more consistent in your sound? To keep churning out the same stuff?

GS: No. In a way I see it more from a DJ’s perspective, like ‘they must be sick of this by now’. I started to see the pattern, see when it was getting really cheesy. It starts to become formula…when we started to make music, it wasn’t about ‘let’s do a jungle remix of a Madonna track’ or whatever. We were trying to do something raw, something fresh, something new. I think it was about 2000 when I realised genre was becoming a kind of marketing tool, everyone was waiting for the next big thing; you know, ‘we can rinse a bit of money out of the 2step scene’, or whatever. But at the end of the day I got into this to make music, so I threw my studio away, decided to do something different. You’ve got to do stuff for yourself first. You’ve got to think ‘this is what I like’, and then work it out from there. If you’re going for impressing other people all the time, you’re going to get lost. For me, the studio I’ve got at the moment, I really find it hard to drag myself out! [laughs] I’m totally addicted. It’s still a magical place for me.

Earlier on, the focus was on trying to get the music out to people, but that’s so easy to do now. The way I see it, the dream has come true! A lot of people were negative about the mp3 thing, but I think that was the major record labels realising that they’d been cut off, but they still had the media and all that. So they spread this negativity about it. But really it’s the best thing that could ever happen for the recording artist. For making money, it might not work – but if you’ve got something that’s really good, everyone can hear it. I mean everyone.

This Friday, May 6th, A Guy Called Gerald plays Dance For Japan, a benefit gig in Barrow In Furness, Cumbria. For more information, go here