Call me a naysayer, but some of the recent talk concerning the resurgence of smoothness in popular music, inspired primarily by the slick stylings of US outfit Gayngs, just doesn’t sit right with me. It smacks of a smirky, ironic approach to pop that I simply can’t get behind, being mere shorthand for a single aspect of the music under discussion – the ease with which it is digested and absorbed. What of the heartache, the poignancy, the darkness? In other words, the stuff that keeps the listener coming back to these songs, time and time again?

British art-pop pioneers 10cc have been namechecked as ‘smooth’ operators par excellence, largely due to the influence of their 1975 single ‘I’m Not In Love’ on the Gayngs aesthetic. But while that single wafted to the top of the charts on a cloud of multitracked vocal bliss, there’s grit at its heart, a painful truth that belies its sonic perfection. In addition, I can’t help thinking that if ‘smooth’ is a summertime thang, then 10cc are more autumnal, delineating a liminal space between light and dark, warm and cold, sweet and sour… uh, you get the idea.

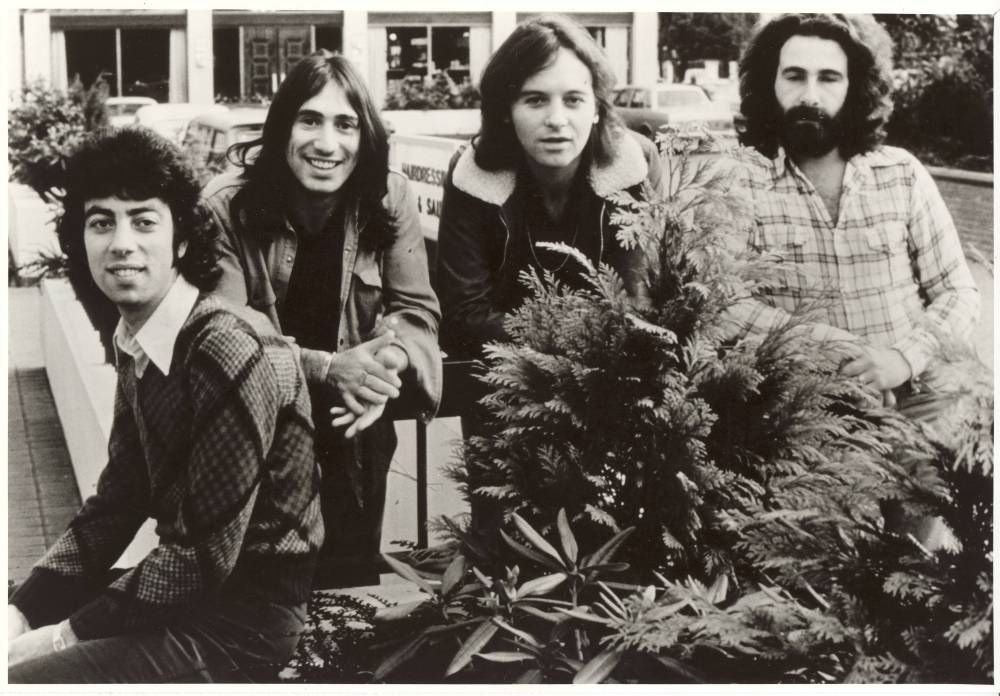

What’s more, if we delve deeper into the oeuvre of the Manchester group (whose original configuration comprised Graham Gouldman, Eric Stewart, Lol Creme and Kevin Godley) we find that it’s way weirder and more diverse than any one adjective can encompass, especially ‘smooth’. Bizarre near-dub experiments (‘The Worst Band In The World’), interludes of music concrete (‘Un Nuit De Paris’, ’24 Hours’), funk rock songs about common-or-garden ailments (‘You’ve Got A Cold’), sinister confessionals from bombs planted on planes (‘Clockwork Creep’) and a recurring taboo-busting theme of money and power as the motivating factors in human activity (‘The Wall Street Shuffle’, ‘Art For Art’s Sake’, ‘I Wanna Rule The World’) align 10cc not with Michael McDonald and James Taylor – but with perverse polymorphs such as Steely Dan, Todd Rundgren and Sparks.

It’s telling that one of 10cc’s later albums, 1980’s Look Hear, came with the blunt enquiry ‘Are You Normal?’ emblazoned on its sleeve. This question could serve as an epigram for the group’s career, during which they looked upon the human condition with a combination of prurience and bemusement. 10cc alchemised the mundane into the uncanny, as on the gorgeous, Beatles-esque ‘I’m Mandy, Fly Me’ which used an airline poster as the launchpad for an adventure in a fictional dimension. Their commentary might seem laconic, even cynical, but Strawberry Studios in Stockport, their original HQ, was evidently a space where dreams and nightmares were allowed to run amok before being corralled into exquisitely crafted pop songs with disarmingly odd angles.

Although the group have released albums only fitfully since their ’70s heyday, they still tour with sole original member, the congenial but precise Graham Gouldman, at the helm. In addition, they have been sampled by Hip Hop producers such as El-P and the late J Dilla, whose ‘Workinonit’ from 2006’s Donuts plays fast & loose with the elastic brilliance of ‘The Worst Band In The World’.

10cc’s music endures – outside the confines of the trad canon – not because it epitomises a single aspect of mainstream rock, but because it’s damn near impossible to summarise in a single paragraph, let alone a single word.

Graham, tell me about your experience of writing bubblegum pop prior to forming 10cc.

Graham Gouldman: I was writing songs for other people during the ’60s, people like The Yardbirds, Herman’s Hermits, The Hollies. That was sort of ’65, ’66, ’67. Then in the late ’60s I met up with some guys called Kasenetz and Katz, who had a bubblegum record label. They wanted to legitimise their outfit and were talking to all kinds of different writers to work for them. At first I was thinking it wouldn’t be right for me, but then I thought, "To hell with it." I was going through a bit of a quiet patch and it was also an opportunity to work in New York, which I wanted to do. Anyway, the upshot of it was that I did it and got fed up with it. I didn’t like it. I said to the guys there, "I’d like to take all the songs that I’ve written and record them, I’m involved in a studio back in the UK and I’ve got some musician friends who I’d like to work with on these tracks." They said, fine, and that went some way to bringing 10cc together. That was my brief, but actually quite useful, encounter with the bubblegum industry.

You mention that it was a useful experience. Did it feed into 10cc?

GG: I think everything you do seeps into everything else you do. For example, we were lucky enough to do two albums with Neil Sedaka. We did one prior to forming the band and one just after. And there’s no doubt about it, that was a good example of learning from one of the masters. Just about general musicianship, the way he played and sang… it was inspirational to be with him, as well as to work with him. I think we learned a bit about songwriting craft as well. But then you learn from everyone you work with.

When you worked with Neil, were you given a brief of some kind?

GG: Well, all that happened was that our manager had met him in New York and told him about the set up we had with our own studio. We were like a kind of self-contained music unit, at that point 10cc were virtually the house band at Strawberry Studios, so we’d play on lots of different sorts of records, do backing vocals, write football records, do loads of stuff, you know. Another thing, which also applies to the bubblegum period, was that it brought business to the studio, we needed to keep working, we were all involved in it and wanted to make good. So that affected what we did as well. We decided, look, you know, "We’re not interested in making football records but if we’re going to make one, let’s make a bloody good one!" So we didn’t really refuse anything. I think that attitude was healthy. But Neil at the time was working at Batley Variety Club, a massive luxury working men’s club up in Yorkshire, and our manager said, ‘The boys are in Stockport, which isn’t that far, why not do a trial recording with them and see if you like it?’ Well, he did like it, so we did the whole album, then another after that. His aim was simply to do a good album. He had these great songs, and we did everything very simply in those days. I went to Leeds to sit with him, got all the chord charts, then we went in the studio and Eric [Stewart] would engineer, Lol [Crème] and I would play guitar, Kevin [Godley] would play drums, Neil would play piano and sing the lead vocal. Then afterwards, we’d go, "Right, we’ll put some bass and backing vocals on, some extra guitar, maybe another keyboard, some of the tracks had strings on…" Whatever it needed.

So Strawberry Studios was the Brill Building of Northern England?

GG: There was a little element of that. I suppose the only difference was that because it was a commercial concern, we couldn’t pick and choose what we recorded. We’d have your Auntie Edna coming in, wanting to record all the songs she’d learned as a kid, then we’d have The Sid Lawrence Orchestra coming in and doing a session. It was a real mix, as it was in most studios. It was full of people that just wanted to make records.

The proto-10cc outfit Hotlegs – whose heavily rhythmic hit single ‘Neanderthal Man’ sounds oddly krautrock-ish in retrospect – featured Creme, Godley and Stewart but not you, at least initially…

GG: Hotlegs started, I think, when I was in New York with Kasenetz and Katz. I got involved with it because the boys had a big hit with ‘Neanderthal Man’ and they were going to go on the road, and they asked me to join them on tour. That kind of petered out but the four of us were left thinking, ‘There’s something happening here.’ We were involved in the studio and when the studio wasn’t working we started writing songs together, just for fun, really, and recording them, until we hit ‘Donna’ and we thought, "Ooh, we might have something really special here," although that was originally going to be a b-side for a track that Eric and I had written called ‘Waterfall’. That song was going to be released on the Apple label. We were waiting to hear whether that was going to happen and while we were waiting we thought we might as well do a b-side for it, and as Eric and I had written the a-side, Kevin and Lol wrote the b-side. As soon as we’d recorded it we knew it was more commercial than the other track.

Did you have any idea of the direction the band would take?

GG: The point of the band was that we didn’t have any orientation or plan, we just did what we wanted to do. We didn’t think. We just did.

Which resulted in something unique. Take the subject matter of your songs, for example… just taking three songs from the debut, ‘Iceberg’, ‘Clockwork Creep’ and ‘Ships Don’t Disappear In The Night (Do They)’ are hardly traditional Top 40 pop/rock fodder.

GG: Well, we always wanted to keep ourselves amused and stimulated by what we did. There didn’t seem much point in doing anything that anybody else had done. We had no A&R man breathing down our necks. We were lucky because we were completely self-contained, we had our own studio, we played and sang everything ourselves, Eric engineered as well. It all worked out that there was no outside influence for us at all. That was one of the main elements of the band, that we had complete freedom. We also had an attitude towards each other’s work that was always very, very positive.

There was no rivalry between the four talented songwriters in the group?

GG: I think there was unconscious rivalry between the two writing teams, which was always very healthy, I thought.

Did you ever have arguments in the studio?

GG: No. Because the idea was that we would record everything that anybody wrote. The principle being that if you thought it was good enough to record, then I’ll go along with that. However… if I can think of a way to make what you’ve done better, I will tell you what I think should happen. In other words, whoever wrote the song, it was adopted by the four of us, as if it was all our own. Once you’re stuck with this song, whether you like it or not, what are you going to do? You can’t sit there and say, ‘Well, I don’t like it.’ You’ve got to say, ‘Well, I think we can make it better by doing this.’

So instead of doing each other down, you’d bring each other up?

GG: Correct. Yeah. And it worked brilliantly… for quite a long time.

But it eventually stopped working…

GG: Yes! But the original split when Kevin and Lol left [in 1976] wasn’t to do with that, it was to with a certain element… it was a bit of a treadmill, a constant cycle of writing, recording, rehearsing, going on the road, then starting again. Which to me, was everything I’d ever wanted! To me that was not a problem, it was absolutely brilliant. But there was an element of Kevin and Lol feeling that they weren’t being stimulated anymore, I think… but the main thing was they’d started recording an album which demonstrated a thing called the Gizmo, that attached to a guitar…

This was the Consequences album? [an ambitious three-disc opus based around a ‘revenge of the elements’ concept which featured a running commentary from Peter Cook and guest vocals from jazz legend Sarah Vaughn]

GG: It turned out to be a triple album, so you can imagine how long that took to do, and it was cutting into 10cc time. It came to the point where Eric and I had to say to Kevin and Lol, "Look, you’re going to have to choose. What’s it going to be?" And they said, "We’re going to stick with the Gizmo."

Do you think they ever regretted that decision?

GG: Well, Kevin and I have talked a lot about it, he’s the only member of the band that I have any contact with, we actually see quite a lot of each other, but what we both thought was that both sides were kind of stupid. 10cc were big enough, we could have taken a year off. Like, "Go away guys, do your album, come back when you’re ready." But that didn’t happen, unfortunately. Although Eric and I carried and we were quite successful without Kevin and Lol. But it changed.

What was the immediate effect of the split on 10cc?

GG: Well, I suppose we lost our more avant garde element.

The experimental edge.

GG: Yeah, yeah. Lyrically, it didn’t have that… although Eric and I are good, we’re good, it wasn’t the same because Kevin and Lol were brilliant.

I have to say, though, I think the first album you put out following the split, 1977’s Deceptive Bends, is my favourite 10cc album…

GG: Well, a lot of people say that, and it’s one of mine as well. We were very, very proud of that album, because we felt people would go, "Yeah, right, you’ve had it now, the creative force has gone," which is ridiculous, but there were things like that going around.

Song-for-song, Deceptive Bends is extremely consistent as well as adventurous. In top three terms, that would be followed by How Dare You [1976], then Sheet Music [1974].

GG: It’s always interesting to hear that and kind of gratifying. I think Sheet Music is generally accepted to be the best, the people’s favorite album. I think there’s a book called 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die, and of all the 10cc albums, that’s the one that’s in there.

Do you agree with that assessment?

GG: I do. I think we were all very focused. It was great fun too. There was another element to that album as well, in that Paul McCartney was doing an album with his brother Mike McGear in the studio at the same time. They were coming in evenings and working until the wee small hours and we used to come in mornings and work through the day. So his presence was quite an influence, I think.

You think the magic rubbed off on Sheet Music?

GG: I know it did. Absolutely.

You were in the enviable position of being both a albums band and a singles band unlike ’70s contemporaries such as, say, Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin, who were both focused on making their albums monolithic statements and less bothered about having individual hit songs. Did you acknowledge this duality at all? How did you perceive yourselves?

GG: I don’t think we perceived ourselves as anything. You know, people said, "Well, what sort of music do you do? Where do you see yourselves?" We were like, "Well… we’re us! We just do what we do. You pigeonhole us if you want to – if you can – but really, it’s 10cc music."

I tend to think of 10cc as being in a small cadre of very clever groups who emerged around the same time, who were capable of writing in a number of styles and covering a wide variety of lyrical ground, some of which was extremely unorthodox, but who nevertheless had a signature sound. Steely Dan would also be in there, as would Sparks.

GG: Well, I’m very pleased to hear that. That’s the joy of having your own band. I do a lot of writing for other people, and while you’re writing you go off into these worlds of mad fantasy… stupid or funny, odd, bizarre lyrics, and your writing partner will go, "Wow, what was that? It was amazing!" and you go, "No, forget it… no one’s going to record that." But if 10cc were still recording then we’d definitely do it.

What kind of music were you listening to outside of the band? Were you keeping an ear out for what was happening in pop and rock at the time?

GG: We weren’t consciously keeping an ear out but we used to listen to a lot of music. We used to listen to a lot of Beach Boys, Beatles, Steely Dan, Motown, Bacharach and David, rock ‘n’ roll… everything that was good.

I find the reggae element interesting. I guess most people would identify this influence as becoming evident circa Bloody Tourists [which featured the classic ‘Dreadlock Holiday’, a song this writer assumed, in his youth, to have been performed by a group of black musicians rather than three pasty Mancunians]…

GG: It was there much earlier, I think. I used to listen to bluebeat and ska in the early ’60s. Ours was a kind of… cod reggae, I guess. It might also have been due to the fact that we used to go on holiday to the West Indies quite a lot. ‘Dreadlock Holiday’ was written after I’d been to Jamaica and Eric had been to Barbados, and we just started talking about our experiences.

As early as Sheet Music, the use of sound effects and innovative production techniques recalls the work of dub scientists such as King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry… I’m thinking of the ear-bending sonics of something like ‘The Worst Band In The World’ [note: this elasticity is also mirrored in the album’s excellent Hipgnosis-designed album sleeve, which depicts the group tugging the yellow border surrounding their photograph into the frame itself].

GG: We weren’t aware of that. I think that was because we had a certain amount of instruments at our disposal, we had our own studio, we had the time, and we could experiment. When we wanted a sound, we’d imagine it and try and go after it. These days what you’d do is if you said, "You know what? I think we need a 250 piece choir on this," you’d go straight to your keyboard and there it would be. Of course we didn’t have that. That luxury didn’t exist in the mid ’70s, so we did it ourselves. And of course, we created something unique. Whereas now, you have access a billion sounds… but so does everyone else.

So you were forced to be inventive?

GG: We loved being inventive! We’d go, ‘You know what? It sounds like we need a keyboard, a piano, but how can we make it sound different?’ So we’d try an echo, or put it through this, or mic it up in this way or that way… but what it boils down to is that you can have the best production in the world, but if the song isn’t any good, it’ll be crap. Whereas vice versa, you’ll have a hit. Or actually what happens is, the song influences everything that happens in the studio. In my experience, if you have a good song, then making the record in the studio is a doddle. A good song stimulates good ideas and everything works, not the other way around.