Filmmakers are often the producers of our dreams, putting us into collective hypnosis. Andrzej Zulawski, who sadly passed away on February 17th, with his bold explorations of sexuality, and horror bathed in a specific kind of surrealism, psychedelia and pathos, cannot be easily placed within the film canon. He was someone who dealt chiefly with how societal constraints and History-with-a-capital-H collide with our deepest fears and desires, and how they can be transposed to the screen in a distinctively hysterical, visceral manner.

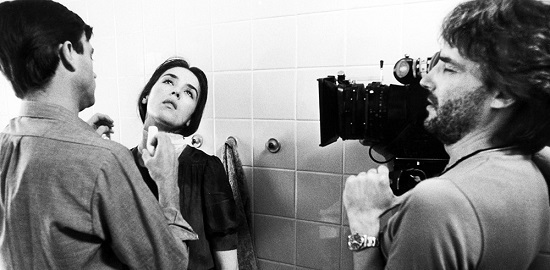

It is a good occasion to reflect on this artist’s complex work as his films, unknown in the UK for decades, have started to re-emerge in unexpected places. The notorious Possession (1981), a marital break-up and supernatural horror film set in Cold War West Berlin, has brought Zulawski a cult following, even though it was banned in the UK on release as a ‘Video Nasty’ for its extreme graphic content. As well, the music label Finders Keepers has released the work of Andrzej Korzyński, the composer of the uncanny soundtracks to Possession and Third Part of the Night (1971). (1976). Not long before his death, Zulawski completed his last film: Cosmos, an adaptation of the novel by Polish emigre Witold Gombrowicz, which premiered at Berlinale two days before his passing.

Żuławski fascinates because he can be counted among those handful of Polish or Eastern European directors who made a career in the West, and who managed to speak a universal language, understood outside their native country. These directors brought something specifically eastern to the table: a kind of freedom and irrationality, which is not simply madness or lack of reason, but a creative dialogue with certain traditions of the Western Enlightenment. This is something which made the sardonic, auto-ironic approach of Roman Polański famous, but with Żuławski, I’d also count the increasingly recognised genius of Walerian Borowczyk, Jerzy Skolimowski and — to a degree — Andrzej Wajda. These directors all made films in the British context, suffusing them with specifically English features. Except for Wajda though, who is Poland’s most important national director, they were local enfants terribles of cinematography and never really appreciated in socialist Poland, with all of them escaping to France, a country with an extremely rich film tradition, and that offered a unique field of exploration through the Nouvelle Vague as well as the social effects of May ’68 and their attendant libertinism and sexual freedom.

Born in 1940 in wartime Lvov, Poland (now Ukraine), Żuławski observed the worst atrocities of the 20th century firsthand, something he would return to obsessively in his visionary films such as Third Part Of The Night and The Devil (1972). If we can say of JG Ballard that his writing wears the shadow of an internment camp in war-ridden Shanghai, and if Roman Polanski’s films of pain, trauma, sickly sexuality and claustrophobia reveal a childhood witness to the atrocities of the Cracow ghetto, then there’s no doubt Zulawski’s childhood traumas form the motives to which he obsessively returned throughout his career: war, isolation, madness realised in taboo eroticism, violence, evisceration — all informed by crazed Polish Romanticism. This is what gives Zulawski a special sense of vision. Even when he talks about the specifics of Polish history – Third Part of the Night’s reflection on Polish conspiracy under the Nazi occupation of his hometown, The Devil’s concern with the 18th century partition of Poland – he’s always really speaking about the impossibility of combining rationality with the ugly reality of human desires.

Incest, rape and sexual murder are the order of the day in his cinema. All his films are camouflaged horror movies. in Third Part Of The Night, as if the war wasn’t enough, conspirators earn money by suckling lice for Nazi medical experiments. Blood and viscera splatters everywhere in this world. His special interest lies in human beings confronted with claustrophobic situations that shake their very existence. They live in besieged cities, they’re imprisoned and tortured, they’re often insurgents or revolutionaries. Their sexual transgression is often a result of being driven to the extreme, and reveals how in fact the world and history move in mad, irrational ways, or how the evil and harm of wars and history has its particular effect on people.

A special place is reserved in his work for women and their desire, though many would argue this place is misogynistic and sexist. In Possession the story centres on a woman who discovers forbidden lusts and decides to go after them everywhere, no matter what the consequence. But — we could ask — aren’t his lusty, hysterical women always just a depiction of a male fantasy? In Public Woman (1984), there is typical male fantasy: a theatre director projects Dostoyevsky’s The Devils onto both the play he’s directing and the actress with whom he’s having a sexual affair. Numerous women are violated, beaten and raped in his films and it’s often shown in the most disturbing, abject manner possible. What stands against it is precisely his most notorious work, Possession, which has been read as a visceral supernatural horror flick in which “a woman fucks an octopus”, but is in fact one of the most harrowing and truthful renderings of a marital break-up that exists.

Despite his ostensible sexism or even misogyny, Żuławski keeps resonating with many female viewers with his mixture of rampant sexuality and exhibitionism. In Possession, Isabelle Adjani created one of the most extraordinary female performances in cinema history as Anna, a woman going mad after she embarks on a romance with a monster, residing next to the Berlin Wall. Living on sex like a vampire on blood, she is famously seen having a miscarriage in a U-Bahn station, maddened and exuding vomit-like gunk from all her orifices, very probably what triggered the final ‘no’ from censors. Zulawski mocks bourgeois conventional sexuality, rendering it unbearable – we see Anna can never get an orgasm from her polite, nice functionary husband, who grows obsessed with his wife’s coldness and has her followed. The political madness of a city under the constant scrutiny of armed soldiers and behind barbed wire is constantly echoed by madness stepping on individuals, leading eventually to a third-world-war verging plot, transporting the film onto yet another genre-level.

There’s a parallel interpretation to Żuławski’s misogyny, in which women are actually empowered and are given the courage to act out their deepest fantasies. In Posession, the demon can be many things: Anna’s anxieties, her neuroses taking the shape of an evil monster. The monster, as we know from Żuławski’s life situation then, could also be a misogynistic punishment to unfaithful wife and beautiful heroine of his early Polish films, Malgorzata Braunek. At the same time, the chronically decaying monster, built out of corpses, which Anna brings him, can also stand for the traumas his generation had to go through.

Żulawski’s genius was to see the personal as political, and the visceral and sexual as coming from social and political oppression. Incredibly stylish, pitched between excess and austerity, his is a world torn between Marx and Coca-cola. The choices of many of his generation bore serious traces of reacting to a trauma, but still he remains chiefly a Romantic: revealing that love is the darkness, against the common, desexualized, sanitized convictions of capitalism.