Xhosa Cole appears at Flatpack Festival on 25 September

In his 1986 documentary film Handsworth Songs, the director John Akomfrah uses the West Midlands suburb as a lens through which to tell a story of Black life in post-war Britain. Why did he choose this area? Though Handsworth – in the North West of Birmingham, just outside the city centre – had seen civil unrest in the 1980s, so had comparable multi-ethnic inner-city areas like Moss Side or Brixton.

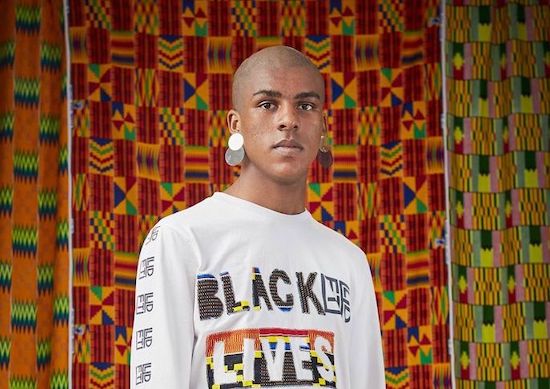

None of the Black Audio Film Collective – the group of sociology, psychology and fine arts students who went on to produce and distribute the film – were from the area. Instead, what they understood was that Handsworth was an important site of cultural production, where networks were set up away from the capital to distribute collective joy as well as collective anger through music, dance, poetry, or just simply socialising. Xhosa Cole, the 24-year-old jazz saxophonist, describes himself as a product of Handsworth and that same cultural legacy.

“It’s a bit like Harlem, in England” explains Cole, 24, attributing the comparison to the Nigerian percussionist Lekan Babalola, an important mentor who lives in the area. "It’s not necessarily the central hub of Birmingham, but creatively, artistically and culturally there’s been so many direct influences.”

Steel Pulse came from the area too – their Handsworth Revolution album being arguably the starting point for British roots reggae and dub in 1979. Likewise, the poet Benjamin Zephaniah.

“Sometimes the best places get the worst raps in the news, we’ve never had any problems here. Just look at the last hundred years, from the Irish community to the Windrush community, various Indian and Pakistani diaspora, and more recently Eastern Europeans and the East African community. It’s this melting pot of different languages, conversations, ideals, perspectives, all in this one hub. It’s only been a positive experience growing up in Handsworth. It has difficulties in support and investment from the council but artistically it’s always been a kind of beacon internationally. It’s given me this really wide and broad outlook on the arts, and really set me in my tracks to whatever I’m doing.”

Ace Dance & Music (standing for African Culture Exchange) would be the early catalyst to a life consumed by music. “My dad was a Rasta” explains Cole, “and very keen for us to connect with our African heritage.”

Growing up, Cole absorbed an enormous amount of different influences and perspectives – so much so that it was only really through studying jazz music that he began to understand himself as part of a wider Black diaspora. “It was in getting to grips with the history of this music, and I don’t just mean in the States but more locally in the UK, that I started to really understand my identity as a Black British man” says Cole, “this Black-centric music came out of a legacy of diaspora Blackness. When you’re around so many different people and come from a mixed heritage background, sometimes you can have so many people that you empathise with, that it can sometimes mean that don’t have an anchor or roots.” Cole describes himself as “always digging around” – books, records, documentaries, conversations with other musicians.

In 2018, Cole was spending day and night in the practice room alongside working as a steward at Birmingham Symphony Hall when everything changed. He won BBC Young Jazz Musician of the Year. “It’s easy with these sort of things to burn out, or not really have longevity, but I was lucky enough to have great people around me, who continued to keep pushing me to move forward.” As is already being evidenced by a varied and progressive career, Cole was pleased with the award but careful to keep his eyes on the real creative prize. "It’s one thing in the arts to think about your career, but it’s another thing to keep in mind artistically the direction you’re going in, how you’re developing.”

That development was tracked at first through collaborations – 2018’s improvisation record Autumn Conversations with Birmingham electronic duo EIF, and guesting on Soweto Kinch’s The Black Peril album and Rachel Musson’s I Went This Way . And then the pandemic hit. As tours were postponed, and then postponed again, he carried on his research into 20th century Black creative history, and taught himself to drum at home.

The murder of George Floyd in May 2020, and the global response to this killing became the catalyst for an important development in Cole’s artistic journey. Stationary Peaceful Protest, a collaboration with the animator Shiyi Li, was his most personal and political work to date – with Cole contributing not just music but a monologue, forming a twelve-minute animated film.

“There was something important about it,” explains Cole, "vocalizing the specific nature of specific challenges we face internationally and in this country. There are things that music can say that words can’t, and things that words can say which music can’t, so I wanted to use both. I wanted to show the audience my experience of going to the BLM march in Birmingham in May 2020. It was a time of questions really. I wanted people to see how not black and white [the situation] is, [but] how many grey areas there are and how many different lines of enquiry there are in such a complex subject matter.”

At a time of particular forward-motion for UK jazz, Cole used his debut to make striking connections between jazz’s vibrant present and its past – K(NO)W THEM, K(NO)W US is rooted in homage to musicians like Thelonius Monk, Ornette Coleman and trumpeter Woody Shaw without ever being nostalgic – coming from a serious love of bebop, its playing is fierce, cacophonous, minting new expression to old forms.

“Normally musicians record and then tour the record, but for us it was a case of musically being on a high from the tour – having that trust and connection – so we went into the studio directly after. We recorded the rep we were playing, and that was the rep of these amazing songwriters and jazz musicians.” Featuring James Owston on bass and James Bashford on drums, the main sonic relationship on the record is that between Cole and trumpeter Jay Phelps – on album standout ‘Untitled Boogaloo’, the two are in serious symbiosis, complimented by a searing guest spot from Soweto Kinch.

The album’s title is a riff on a quote of Dizzy Gillespie’s that Cole found whilst buried in research. “The quote was about Louis Armstrong” explains Cole, “now it’s an oral quote, so it’s very hard to know whether he was saying “know him, know me” or “no him, no me.” So, I’m kind of saying, “no them, no us.”

“So often in a contemporary context our identity is defined against something else – not being white, not being women, whatever the case may be” says Cole of the message behind the release, "but if that’s the case, our identity can’t exist if others don’t exist. It’s a unity thing, not only from the perspective of the past – without the greats, our forefathers, we don’t exist – but also without our neighbours we don’t exist.”

On Saturday 25 September at Birmingham’s sprawling multi-venue arts festival Flatpack, Cole is showcasing his most ambitious commission to date – a live score, with an eight-piece band, of the neglected 1989 US silent film Sidewalk Stories. The story of Sidewalk Stories is important. A retelling of Chaplin’s 1921 classic The Kid, it featured a majority Black cast, was made on a low budget and was praised for breathing new life into a bygone mode of cinema, drawing lines between cinema’s history and the contemporary New Black Cinema. (Incidentally, the film makes a terrific pairing with that other 1989 Black cinema masterpiece, Do the Right Thing.) Though the film won the Prix du Publique at Cannes, and a twelve-minute standing ovation, Lane struggled to get another film released, not directing a feature film for nearly two decades after its release.

“I was quite daunted by it” explains Cole of the film, “it’s got so many engaging scenes, it’s stylistically so strong, there’s a lot to work with. So, it’s a case of, how do I take on the influences that inform the aesthetics of the film, of its’ time, and how do I bring my contemporary influences and aesthetic into this?”

Cole describes the eight-piece band he has prepared as “a compilation of all of my favourite improvisers really. Some are more into the free scene, some are more straight jazz. It’s about composing the frameworks within which people have certain freedoms to interpret the film for themselves, but also some strong musical themes that carry the audience through the narrative of the film.”

“I’m a bit of a maths fiend, whenever I’m teaching in schools or we’re improvising with students, I’m always interested in the combinations of possibilities and of players. With eight people in an ensemble, there’s 256 combinations of ensembles that you’ve got in there – including everyone playing, nobody playing, duets, solos. For me, it becomes, how do I make it really interesting in terms of timbre, and texture?"

Cole has come of age during a particularly healthy flourishing of UK jazz – but also during a wider reappraisal and contextualisation of UK jazz history. For sins of both omission and commission, the contribution of Black British musicians has been a neglected part of the sanctioned histories of both British music and wider jazz histories.

"I recently spent some time at the database of Black British jazz musicians in the 90s” explains Cole, “and it was like… woah. I think it’s inspiring to see what young musicians are coming out with now, but maybe I’m…” he pauses, "looking back to look forward. I think it’s easy for us to steamroll over the innovations that came out of this country, which isn’t really documented well for several reasons.” explains Cole. “Cleveland Watkiss, Steve Williamson, Courtney Pine. people know the name Courtney Pine but have you checked out the music he was really making? It’s groundbreaking stuff. Another thing to clock, though, is that recognition is coming. Nu Civilisation Orchestra just did a gig celebrating the music of Joe Harriott. For me that’s been a learning experience. I’m always inspired by my peers, it’s always about the level of excellence. Sure, it’s about feeling it, it’s soul music, but it’s intellectually dense music. It’s the emotional element, the spiritual element and the intellectual element, and that’s the balance.”