A few miles from where I sit typing this in Brighton, East Sussex, there is a care home called St Dunstan’s. It was the home of a man named Henry Allingham, the penultimate surviving British veteran of the First World War, who died in 2009 aged 113. This year a great deal of commentary and an enormous number of events have taken place across the country to mark the centenary of the outbreak of a war so recently faded from living memory. Only five short years after the death of its last living witnesses, the Great War is in the process of a kind of mass remembrance. Perhaps this communal act will serve to usher it back into a remoter stage of history, removing it further from the real and cementing its place firmly and exclusively in the unimaginable.

The war that was sold to the public in 1914 as patriotic, decisive and brief has by now been long enshrined in the public consciousness as only the earliest atrocity of a very dark century. It’s also the earliest large-scale conflict to exist on film (although much of the ‘combat’ footage you and I have seen was in fact staged for the newsreels), and as such its images are burned into our collective retinae. Though the war’s immortalising in the arts is probably more attributable to literature than to film, the iconography of the conflict, its visual signifiers, are a veritable inventory of props for set designers and art directors everywhere: poppies, trenches, tin helmets, barbed wire. All used and overused, reproduced into meaninglessness.

But still it feels that there are far fewer movies dedicated to the Great War than to the Second War, the war against Hitler, Mussolini, Hirohito. Why might this be? When we consider the development of narrative tropes and visual storytelling techniques, a few possible reasons are presented. Firstly, the earlier conflict lacked such obvious moral compass points as ‘Freedom versus Nazism/Fascism/Imperialism’, and most movies still rely on a clearly definable Good and Evil dichotomy (though many a superb drama has been staged on this threshold.) And secondly, the total shattering of the entire Western Front by four years of artillery fire and troop movements left the territory of the war an indistinct mass of mud and ruins. Perhaps even more than Vietnam, stories of the Great War are firmly dependent on their setting of complete topographical chaos. The classic ‘adventure’ war film, closely related of course to the classic action film, requires the audience to be completely spatially aware, to orientate themselves, to empathise. The futility of the Western Front stalemate does not lend itself to stories of military objectives, even ostensibly ‘serious’ ones like The Longest Day, The Dam Busters, or Saving Private Ryan. In a war more often remembered for its horror and inhumanity than moral heroism or strategic intelligence, narratives can only be based upon themes of pity, fear, injustice, naiveté, and waste. Heavy ideas and grim reminders: not a bankable recipe for box-office success.

And yet from village halls to cosmopolitan arts institutes, there have been screenings throughout the year of significant films about the First World War. Here in Brighton, September was bookended by screened restorations of Stanley Kubrick’s Paths Of Glory and William Wellman’s Wings, which won the very first Academy Award for Best Picture in 1927. Understandably, the highest number of Great-War-themed films were released in the inter-war years, as tensions quickly regrew and nations struggled to find their own identities after such colossal bloodshed and displacement. It is from this period of silent and early sound cinema that most great canonical First World War films were made: King Vidor’s The Big Parade in 1925, Lewis Milestone’s 1930 adaptation of the hugely successful memoir All Quiet On The Western Front, and Jean Renoir’s masterpiece The Grand Illusion in 1937, among others. All of these have been written about widely over the last seventy-five years, and many have been reassessed especially for the centenary in print and online.

For this article I decided to dig a little deeper, and chose ten films about the First World War that are under-seen, outright obscure, or unjustly overshadowed by works like those previously mentioned. I tried to make it an international list, although the availability of many films has been dictated by orthodox standards of cinematic reputation: the French and German films were easy to find and have good English subtitles, whereas the films from Russia and Romania weren’t and don’t, no matter how well known they are to their original-language viewers. (I cite the high view counts on un-subtitled YouTube clips as proof that ‘obscurity’ is of course very relative.) In many respects it’s an arbitrary list, varying wildly in style, subject, genre and quality. But taken together, the films offer an amazing multitude of perspectives on the war’s significance, and different ways in which the imagery of the Great War has been codified and employed to serve the cause of everything from pacifism and poetry to propaganda and exploitation.

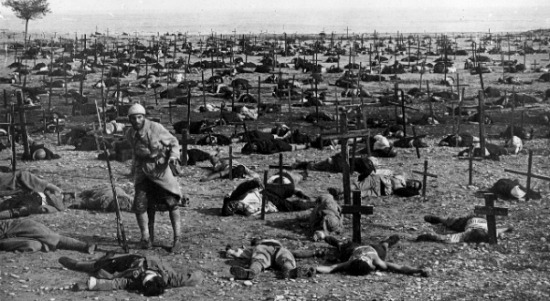

J’accuse! (Abel Gance, 1919)

Abel Gance’s epic J’accuse! should take its place at the beginning of the story. Filming started even before the signing of the armistice, and Gance was able to use real French soldiers on leave as extras. When the film was released in 1919 it was met with universal praise, and immediately elevated the status of its director to the highest echelons of the art form. It’s strange that Gance was able to secure the army’s co-operation, as J’accuse! is a vehemently anti-War work of the most earnest kind. Perhaps the top brass had merely skimmed the script with one eye whilst eagerly monitoring the German retreat with the other.

For decades after the advent of sound cinema, Gance’s best work remained unheralded. His reputation among cinephiles has now been pretty well revived, and this is largely due to the advances in restoration techniques and the dogged dedication of film archivists worldwide. Gance himself, like Erich von Stroheim in America, was undone in his prime by the sheer unbearable weight of his own artistic ambition: by the late 1920s his films had simply grown too large to screen. But in hindsight, his breakout film must have seemed near impossible to top in the immediate aftermath of war. J’accuse! makes bold statements in both subject and style. It’s surely the first cinematic attempt to sincerely ruminate on the cost of war and criticise the ideological positions of the Old Militarist class, while it also argues the case for cinema as the equal of any other art form in its expressive and poetic potential.

Its title refers to a famous letter written by the author Emile Zola to the newspaper L’Aurore protesting about the Dreyfus Affair, a political scandal in which an innocent Army officer was prosecuted for treason, leading many to suspect the French government of institutional anti-Semitism. The famous phrase – “I accuse” – became less a personal statement than a rallying call against injustice perpetrated by the state. Abel Gance audaciously adopts the literary giant’s words, and by placing them so often into the mouth of his protagonist Jean Diaz he has ensured that the film will forever stand as a “J’accuse” of his own.

A poet and a pacifist, Diaz is instinctively repulsed by the prospect of war, acceding to conscription only to rescue his lover Edith who has vanished among the panic of the German advance. He eventually finds she has been captured and raped by enemy soldiers, and spends almost the entirety of the war fighting alongside her alcoholic and abusive husband Francois. Fired by the pain of her absence and fortified by the unlikely reformation of Francois into his brother and comrade-in-arms, Diaz becomes an outstanding soldier. But four years of war proves too much to bear, and his discharge and return to Provence as a kind of dishevelled and wide-eyed ranter is as memorable as any of cinema’s divine madmen.

J’accuse! has its legitimate claims to realism, as some footage had been shot on an actual battlefield in the late Summer of 1918, but ultimately Gance’s vision is romantic and technically stylised. Bona fide realism cannot sit comfortably beside the film’s overt attempts at poetic montage and psychological subjectivity. At the film’s conclusion, Gance even allows the figurative to invade the real. The stunning final confrontation is not between opposing armies; instead it’s a visitation by a ghostly horde of dead soldiers upon the villagers who have spent the intervening years in shameful ignorance of the realities of war.

The final third of the film really delivers on its promise to be the first definitive post-war statement of loss, horror, waste, and of course accusation. A montage of the mud-caked boredom of trench life feels far better served by Gance’s painterly pictorial eye than by the proto-documentary intercutting used to accelerate and vivify the later battle scenes. It reminds us that this war began to memorialise itself immediately into the tragic and pitiful images we have become accustomed to. J’accuse! is Gance’s contribution to the War of the Soldier-Poets, as it has so endured in the public imagination, and an example of one of the earliest great directors on searingly heartfelt form.

Westfront 1918 (GW Pabst, 1930)

Westfront 1918 has been overshadowed by the American adaptation of All Quiet On The Western Front ever since both films were released. It’s easy to see why: Hollywood was still edging out Europe in terms of global market dominance, Remarque’s book had made him something of a literary celebrity, and Milestone’s film is grander and more tragic in its scope than Pabst’s lean and bitter ninety-minute downer. All Quiet is a great movie, but like J’accuse!, its aspiration to become a classic can be clearly felt. Lewis Milestone aimed to capture the public’s hearts; Pabst went for the jugular.

Gustav Diessl is the embattled everyman at the centre of the film. Where other narratives (including Remarque’s) focus on the Doomed Youth – barely out of school and dying in droves in the name of international political vanity – Pabst’s protagonist is a married thirtysomething. He trades banter with a couple of grizzled and crude proletarians even older than he. It’s clear from the start that Pabst really isn’t interested in heroics – the front line scenes in Westfront 1918 are about cynicism, violence and gallows humour. “If we were heroes,” one soldier quips blackly, “we’d be home already.”

The battle scenes are impressively scaled and intimidating. The camera tracks quickly along the edge of the front line as the ancient soundtrack is scarred with explosions. It’s as confusing as it ought to be – one moment the horizon is low in the frame, then the reverse angle is pure mud and movement as the soldiers attempt to communicate down the line. By the film’s final scene, in an ad hoc military hospital as full of twisted and gesturing bodies as any Hogarth or Bosch, a war-hungry Lieutenant has finally cracked and become a screaming shellshock victim. Pabst has the unpretentious moral courage to end the film on this note of ultimate weakness, the defeat of humanity.

There is one long central scene that particularly impresses now with its dramatic foresight. During a trip home on leave, Diessl returns to a desperate and bankrupted Germany to find his wife in bed with the butcher’s son. She is terrified of what her war-hardened husband will do; the butcher’s son hurries on his trousers as Diessl hands him back the call-up letter he’s left on the table. Soon this idiotic and exploitative young man will face the same horrors he has just returned from. After the man leaves, Pabst refuses to cut away from this difficult and fraught scene. Diessl washes himself, asks for coffee and eats dinner, all while his wife fusses nervously around, waiting for her punishment. We have no idea how he will eventually address her infidelity. Has she been trading her body for double rations? What is forgivable in a nation crippled by war? This lingering dramatic threat, with the wider issues playing so palpably around the scene’s edges, is ahead of its time by decades. In partial accordance with his two preceding films Pandora’s Box and Diary Of A Lost Girl, Pabst seems to be suggesting that although indignity is forced upon us by external hardships, there may be some part of us that by our very nature perversely allows such indignity to take hold.

Comradeship (GW Pabst, 1931)

Strictly speaking, there is only one scene in Comradeship that portrays the Great War. Less than that, even – it’s a flashback within a scene. But its story is so heavily reliant upon the war’s devastatingly recent memory that it refuses to be interpreted in any other context. Immediately after completing the bleak and damning Westfront 1918, Pabst was seemingly eager to find a story that admitted more hope for the reconciliation of the two major combatants of the Western front, and this story of a mining accident in the industrial areas straddling the French-German border gave him just such an opportunity. Thus Comradeship is as earnestly positivist as can be, as well as a sharply economic and class-conscious suspense drama. It’s all claustrophobia and sweat and outrage, while the visual components of dirt, underground tunnels and tin helmets consistently bring deeply ingrained images of the War to mind throughout.

From the weary banter of professional soldiers in Westfront, the hard-labouring communality of the miners in Comradeship is but a short step. The tunnels run directly under the national border, and there are several scenes on either side of the bricked-up boundary in which both French and German miners joke and mutter about their counterparts. There are a few comments about the war, some layman’s politics thrown around, but by and large the men’s identification as miners seems to outweigh any sour and xenophobic feeling. Pabst cast both French and German actors, and so in keeping with the story’s restorative moral mission, Comradeship is a truly international production.

There is an explosion on the French side, trapping dozens of miners underground in sweltering conditions and with dwindling air supply. A few grudge-holding German miners are shouted down by the strong and earthy voice of worker solidarity sans frontiers, and soon there is a bus full of rescuers heading to the border. However, in a narrative masterstroke of parallel reflectivity, they find the French townspeople up in arms and momentarily blocking their way. The trapped miners’ families are outraged at the lack of information they’re receiving from the authorities, and are on the verge of a riot. There is chaos above and chaos below. After a little confusion, the German rescuers are hurried through the cheering crowds to the gates. Comradeship celebrates the liberating power of grassroots unity, but without labouring its message and overshadowing the pitch-dark, grimy, simmering threat of human tragedy at its centre.

The film’s one brief visual representation of the Western front is a highly effective piece of nightmare-realism. As a trapped and semi-conscious French miner is about to be freed by his German counterpart, he is reminded of the horrible image of gas-masked German infantrymen clambering across the front line towards him – a slow advance of glass-eyed and tube-mouthed monsters. The miner is overcome, and attempts to strangle his own saviour. It’s a powerful moment: freed from the demands of narrative realism, Pabst is able to distil one man’s war experience down to a potent, isolated moment of terror. In doing so proves he is just as capable at framing that ‘War Image’, perfectly horrible and maddening, as later directors filming later wars – Kubrick and Coppola spring to mind – as well as others on this list.

Arsenal (Alexandr Dovzhenko, 1929)

Of all the new knowledge I gleaned through the research for this article, nothing was quite so surprising as the discovery that the Ukraine had actually fought for both sides during the War years. The vast majority of the country’s armed forces allied with the Russian Army, while a small proportion (still a quarter of a million men) were drafted by the Austro-Hungarians. This fractiousness was a consequence of the timing of the War’s arrival: the largely agricultural Ukraine had been modernising its infrastructure and aligning itself more strongly with Russia over the preceding decades, and over the turn of the 20th Century, huge numbers of Ukrainians had migrated to Siberia and Central Asia. A blurring of borders on both sides had inevitably resulted in a Ukraine with complexly opposing cultural identities.

Viewers of Dovzhenko’s most important works today might find it difficult to grasp these distinctions and tensions at play in his grave, portentous montage style. The director’s virtuoso editing presents us with an accumulation of heavily cerebral symbolic framings, an evocation of the strength and piteous hardship of the lives of Ukrainian peasant workers buffeted by the political upheavals of far-off power centres. In practice, this makes his films as alienating as they are bracingly confident, mournful, hyperactive, and possessed of some of the most crisply beautiful black and white photography in the whole of cinema.

Anyone who’s had a few film classes will know about Eisenstein’s montages, and how incalculable their influence has been. But they are rather didactic now both as movies and historical artefacts; they are exemplary of Soviet propaganda and the techniques behind cinematic metaphor and audience manipulation. But critics have helped certain such Soviet works wriggle free of these clinical and contextual trappings. As such, Arsenal now has a towering reputation among serious cinephiles and scholars, as Dovzhenko himself is the go-to example of ambiguity and nuance (and perhaps obtuseness) in the field of Soviet-influenced propaganda cinema of the twenties and early thirties.

Dovzenko’s Great War scenes in Arsenal are fevered confrontations. Amid a disorientating gas attack, a bald and bespectacled soldier stumbles upon another, half buried yet frozen in a smile. The bald soldier begins to laugh maniacally. This strange meeting is then witnessed by a third man, merely a silhouette, who stops statuesquely in indecision. A fourth man arrives – a superior officer, ranting, spitting, brandishing a handgun, and insisting upon further movement, more slaughter, and capital punishment seemingly for the insubordination of affording a pause in the churning chaos. Dovzhenko’s war moves at a fractured and impossible pace, expressed in an overwhelming sequence of portrait, landscape, sculpture and shadow play.

These trench warfare scenes are really just an overture in Arsenal, barely a first act. The great national drama begins as the freshly demobbed soldiers return to a land in turmoil. Dovzhenko stages and shoots the political debates of the Ukrainian post-war power struggle in a way that shows both mob mentality and individual action. As impassioned speakers address the crowd, the director shows the audience turning, cheering, lambasting, one by one and then in groups, a sea of attendees vying for their country’s future. The influence of group scenes like these can be found in the films of later significant leftist directors, from the folk tales of Miklós Jancsó to the partisan realism of Ken Loach.

Filmmakers learned long ago the power of expressive faces in close-up, and how their imprints can remain long after such particulars as story and dialogue have faded from the audience’s minds. The smiling half-buried soldier and the heroic features of the Bolshevik protagonist are cases in point: Arsenal’s plot is difficult to follow, but its human imagery is strong and memorable. Dovzhenko may be a master of Soviet-style editing, but it’s his choice of faces that accounts for the greatest share of the film’s impact. To find the right face in each instance, from leading man to bit-part to extra, and train the camera on it with (pre-) Bergmanesque clarity: this is his craft.

Four Sons (John Ford, 1928)

There’s no smooth way to link a film like Arsenal with the contemporaneous mainstream Hollywood drama Four Sons. They are about as disparate in tone, style and intention as any I’m focusing on here, and the very different positions the war holds in the fundamental morality of each story can be clearly attributed to the conditions of their respective countries’ involvement. Finally and reluctantly entering the war in spring of 1917, American soldiers arrived in France shortly after the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. Thus the sudden Allied reinforcement of the Western Front coincided with the beginning of a long and complex dissolution of the Eastern. As the US entered the war, its position of great economic strength eventually outweighing non-interventionist public opinion, the Eastern allies were bowing out, exhausted and poverty-stricken, trying not to concede their borders too far to the Central powers. Accordingly, in John Ford’s film the war ends up reinforcing the ideals of the Land of Opportunity, whereas in Dovzhenko’s it’s the cataclysm that drained Eastern Europe of its stability, triggering a string of smaller scale conflicts running well into the 1920s.

It’s perhaps indicative of America’s apparent no-hard-feelings attitude to European relations (especially while it was enjoying its short-lived economic boom) that a big studio picture could be made with a German family at its core. The Bavarian village set in Four Sons may be a complete fairytale, but the film’s intentions seem sincere. It assumes that the constitution and values of a family must be the same on both sides of the battle lines. Every mother must want to keep her sons safe however they choose to live their lives; every son must want to be a proud provider; every provincial idyll is subject to the ravages of circumstance.

The widowed Mother Bernle has four sons. One is already a soldier and another signs up; both are killed almost immediately at the war’s outset. The youngest son expresses his wish to emigrate to then-neutral America to work at his uncle’s delicatessen, and the old woman is relieved that at least one of her children may be spared a soldier’s fate. In metropolitan New York, we see that a native German can not only start a successful business but sign up to the US Army too, provided he can persuade the recruiting sergeant of his loyalty to Uncle Sam. (In Ford’s world, a stars-and-stripes tattoo on the bicep is all it takes.) But of course America’s entry into the war becomes a melodramatic twist of fate, and both surviving brothers find themselves unknowingly opposing each other across a smoky studio-set No Man’s Land.

There are some highly predictable plot points, but John Ford races through them with surprising economy to arrive at a third act that genuinely surprised me. Four Sons offers little in the way of visual poetics, but Mother Bernle’s touching reunion dinner with her dead sons, achieved through simple double exposure, deserves a mention for its well-earned poignancy. For the most part this is a broad-strokes drama, a crowd-pleasing product of the big American studio system, yet there is a little more socio-political complexity to be found where Ford targets his ire. He swipes at the German officer class, lording it over the honest Bavarian villagers with cartoonish scowls, but also at the American immigration system, which he seems to believe is choked with bureaucracy and insensitive to human needs. With so many enthusiastic foreigners willing to come through Ellis Island to partake in the American dream, why should the pencil-pushers stand in their way?

Despite the Disneyland version of Bavaria, despite the wall-to-wall histrionics and comedic mugging, there’s something in Mother Bernle’s endurance of loss that remains moving, especially towards the film’s conclusion. It’s the kind of finely orchestrated all-American sentimentality that can’t be entirely shrugged off, even as the film’s age reveals how baldly manipulative the story is. Like in a Frank Capra movie, there’s something in the American promise of peace and prosperity that stands up to cynicism and refuses to die.

Within ten years these principles were being profoundly challenged. Depression-era movies dared to suggest that behind the stock-ticker optimism of the twenties, feelings were very hard indeed. The first wave of American gangster movies put paid to such naïve ideas of inclusivity and honest hard work. And in 1939’s The Roaring Twenties, Raoul Walsh was confident enough to blame the explosion of organised crime on a lack of career prospects for soldiers returning from the front twenty years earlier. This same idea was revisited in 2010 as the starting point for the HBO series Boardwalk Empire.

Quiet Flows The Don (Sergey Gerasimov, 1957-8)

Soviet cinema of the 1950s has not garnered a great deal of international critical attention. Looking back over the narrative of world cinema and its key directors, there seems to be a significant gap between the death of Eisenstein and the emergence of Tarkovsky in the early 1960s. Perhaps Soviet filmmaking had lost its edge and purpose during the period between the death of Stalin (and the resultant process of dismantling his personality cult) and the development of the various New Waves across Eastern Europe.

Made over 1957-8, Sergei Gerasimov’s Quiet Flows The Don is an adaptation of a hugely successful multi-volume novel about the impact of the Great War years upon a Cossack village community on the Don river. Faithful to the scale of its source material, the 330-minute film is a day-consuming affair, unwieldy not only by its sheer length but also its rather overripe conjugal melodrama and the endless complexity of its political content. We follow the Cossack horseman Grigory Melekhov as he restlessly navigates through a life of duty, cruelty, familial disputes and exhausting periods of exile. Hardly the most likeable protagonist, his bullishness condemns both his wife and mistress to short and miserable lives. Modern Western audiences will only blame so much of his conduct on the inflexible societal conditions of the time.

The film is visually influenced by the Technicolor saturation of Hollywood epics, which lends both vibrancy and an inescapable staginess to its depictions of village life. But after the Cossack horsemen of the village are called up for their military service, the colour palette becomes gradually more muted and murky. Where the first third seems overly engaged in enraptured tussles about the indignities of arranged marriage and forbidden love among wheatfields and river rushes, the rest delivers scenes of political disarray among creaking train cars, with dusty and fatigued soldiers barely tolerating the speechifying of self-appointed faction leaders, shouting to fill the void of power after the Tsar’s assassination. At times the tonal transition is abrupt enough to be instantly noticeable: as the protagonist Grigory leaves the village for the snow-deadened wilderness, it feels like he’s walked straight into a different film, made twenty years later.

The Eastern Front’s first cavalry charges are presented with unambiguous heroism. This certainly caught me off guard, as I initially mistook the film’s reverence for the innate horsemanship of the Don Cossacks for support of militarism in general. But there’s certainly no glory to be found as the war rolls mercilessly onward. Scenes of boredom and uncertainty in the trenches are characterised by the weary bickering of the soldiers. Political colours are exposed by their differing predictions for post-revolutionary Russia, and eventually they are hushed, not by a unifying voice but by the grim solidarity of endurance.

Quiet Flows The Don is both obscure and dated, but patient viewers will be rewarded with a feeling that only very long films can cultivate. The changes wrought by the shifting ages are absorbed almost as in real life, rather than expressed by metaphor or signposted by film-school temporal tricks. As the Great War collapses into the revolution, followed by the Civil War, the Melekhov family is broken, reduced, exhausted and extinguished. At the end there is nothing left but an embrace between Grigory and his son, and after nearly six hours of viewing I felt like I too had earned those grey hairs slowly growing into Grigory’s dark and hardened countenance.

Uomini Contro (Francesco Rosi, 1970)

The story of Italy’s involvement in both world wars is frankly rather undignified. As the grand Fascist ambitions of Il Duce were ultimately shown to be toothless posturing, this under appreciated film traces a similarly delusional Italian militarism back further. Francesco Rosi is fairly well known in the history of Italian cinema, but his 1970 film Uomini Contro (translated as Men Against… but released with the much flatter title of Many Wars Ago) is generally overshadowed by his other work from the period. (A recent career retrospective in Sight & Sound barely mentioned it.) It may indeed be that this is one of his lesser films, but it’s as ‘pure’ a war movie as one could hope to find and easily qualifies for inclusion here. Its most impressive quality is also its most alienating: Uomini Contro is almost devoid of humanity. The soldiers we follow simply trudge onwards, advancing and retreating, abandoning vantage points only to reclaim them the next day. It studiously excludes any reference to life before or outside the war, and its portrayal of the military machine as a circus of unforgiveable cruelty recalls Stanley Kubrick’s Paths Of Glory, that touchstone of anti-militarism in cinema.

Whether or not Rosi attempted to portray the Italian front with much realism is rather hard to gauge. The army’s repeated disastrous assaults on heavily fortified Austrian lines take place in a dense Alpine fog that never seems to shift, and so all the dehumanised drama of Uomini Contro is staged upon a kind of grey, nightmarish infinity. Prospects are bleak for the Italians, and the film is broadly a study of mutinous disarray and tension. And as in so many Great War narratives, the blame for the slaughter is placed solely on the officer class, personified here by Alain Cuny as the sharp-eyed and seemingly immortal psychopathic General Leone. In one particularly bizarre scene, Leone pontificates wildly about the successes of the Roman army before ordering the advance of a small group of soldiers wearing huge and cumbersome metal armour. These men totter onto the battlefield in their medieval deep-sea diver’s suits, and the Austrian gunners allow just enough time for the scene to descend into a pitiful Pasolini-esque parody before opening fire and killing them all.

There is rarely respite in the bleak delivery of this material. It makes war seem utterly wretched and that’s exactly what it’s supposed to, for which Rosi should be commended. Two especially decent scenes cleverly exemplify the edgy, mutinous condition of the ailing Italian forces at this point in the war, and the same officer-class egomania as found in J’Accuse!, Westfront 1918 and even the hammy Four Sons. In the first, a Lieutenant is shown how the Austrian snipers have trained their guns to fire precisely through a tiny metal shutter at an Italian observation point; in the second, Leone discovers with surprise that this same Lieutenant has miraculously come through all of his suicidal offensives without even being wounded. And through all this the audience has no idea how their movements affect the bigger picture of the Balkan front, or the rest of the war. This may be the film’s most skilfully communicated concept – there is no sense of scale, no back story, only mountains and infantry, endless mist, desertion, execution, and strafing gunfire.

The Mercenary’s Trap (Sergiu Nicolaescu, 1980)

Hunting down The Mercenary’s Trap became something of an obsession for me while researching this article. This is partly because I happened to visit Romania earlier this year and found it beguiling, beautiful and completely unostentatious. Recent Romanian cinema has been making an impressive impact on the critical community, although many of these films have been bleak exposés of the country’s institutional backwardness. Sergiu Nicolaescu is not exactly a forerunner of the movement; he is remembered mainly as a reliable director of 1970s historical adventure films. The Mercenary’s Trap is virtually unknown outside Romania, and is the only movie in this list to commit so wholeheartedly to genre. It’s serious about its historical context – the post-war uncertainty surrounding the possible unification of states that now make up modern day Romania – but its consistent violence and pleasingly comic-book characterisations suggest that Nicolaescu had more than a passing knowledge of 1970s exploitation cinema. He also certainly knew his Spaghetti westerns: the wholesale theft of Ennio Morricone’s ‘Man With the Harmonica’ theme from Once Upon A Time In The West provoked from me the only real moment of comic incredulity across all ten films. The Mercenary’s Trap may be derivative, but nobody could accuse it of not being entertaining.

It tells the story of a massacre in rural Transylvania by a officer returning from the War to his estate after the defeat of the Central powers. Much of the first third consists of scenes of gruff demobbed drifters, hardened with alcohol and occupied by card games, being recruited either by the psychotic Colonel Gertz or the ragtag retaliatory force amassed to lay siege to the castle. All this has been triggered by a dispute over the peasants’ burning of a sawmill, and the film quickly establishes itself as a kind of feudal Spaghetti western, with the political complexities of the time reduced to a collection of various tattered uniforms worn by a grimacing motley crew, forced to fight dirty among the vast and unyielding snowy forest of Transylvania.

There’s something particularly cynical about how these men are simply bought by whichever guerilla leader chances upon them first. They are guilty, vengeful or cowardly; the war has forced them to commit damning acts, and so damned they remain. Their consciences are irredeemably spoiled, so they might at least make a little money and drink a little hard alcohol while they are drawn inexorably towards their own disgraced deaths. Colonel Gertz is a particularly sore loser, and the film’s best sequence is a deadly game in which his mercenaries are paired off and forced to drink each other incapable. Whoever is unable to drink any further is shot by his partner. It’s a thrillingly cruel and fanciful idea. These kinds of touches, and the numerous scenes of dolefully gritty dialogue in shallow focus shot-reverse-shots, are clear Sergio Leone worship and all the better for it.

Truthfully it’s not a lost classic, but its obvious Spaghetti western influence does help to recast the era in an interesting new light. The backdrop of all classic westerns is the drawing-up of frontiers, the feeling that history is being decided by crude moralities in unyielding territories. The Mercenary’s Trap certainly fits this description, and the film’s immediate post-war setting frees its story from the responsibility of having to represent a wider conflict, where the Dollars-trilogy influence would have been incongruous. Sergiu Nicolaescu recognises the generic potential of his country’s villages and fortresses, with their rotting doors and crumbling walls, and peasants who seem always locked in a mournful stoop.

War Requiem (Derek Jarman, 1989)

The only British film on this list is also the only outright experimental film, and a very high profile one at that. By the late 1980s Derek Jarman was a filmmaker of distinction, and the cast includes Sean Bean and Tilda Swinton in the early stages of their film careers, as well as Laurence Olivier at the very end of his. War Requiem is completely without dialogue and soundtracked by the entirety of Benjamin Britten’s 1962 composition of the same name. Jarman’s film is more reminiscent of experimental theatre than narrative cinema, and as such will likely prove a difficult watch for some. But it’s exactly this approach, this total remove from realism of any kind, that makes it such a powerful memorial to the lost. Though its main character is in some sense a stand-in for Wilfred Owen (whose poetry is the source for the lyrics of the requiem mass), he in turn is a representative of every British soldier.

The trials of conscience endured by ‘Owen’ after his comrade’s death are vividly dramatised in nightmarish religious imagery. A simple description would make this all seem rather overwrought – how else could a dead soldier adorned with a Christlike crown of barbed wire come across? – but in the tonal context of the film as a whole it certainly feels artistically justified. Jarman is uniquely capable of finding the right visual tone to complement Britten’s often challenging and dynamically unpredictable music. He achieves this by coaxing highly expressive and patient performances out of his actors, and also perhaps more crucially by his lighting and set design. He had in fact previously worked as a set designer for Ken Russell in the early 1970s, and this attendance to the surreal, the colourful and the symbolic places him clearly in a tradition with his mentor, as well as filmmakers like Peter Greenaway and Federico Fellini.

In War Requiem, Derek Jarman stages highly metaphoric scenes of distilled grief and sacrifice. So many aspects of the war experience, in combat and on the home front, are expressed in essence by small and simple actions and gestures. One such moment is the sudden switch from play to violence, after the German soldier pelts the British with a snowball as he plays an abandoned piano in the shell of a bombed-out building. Tilda Swinton is the Nurse, standing in for all who suffered the absence and loss of loved ones. In an unbroken take late in the film she progresses through a torrent of emotions, first slight, and ultimately unconstrainable.

The only difficulty comes when the lyrics break through the viewer’s visual concentration. We’re used to the strategic use of classical music on movie soundtracks as signals and cues for emotion, but there are moments in War Requiem when the poetry itself grabs the attention, and it’s hard in these instances to hold in mind the complexity of both the words and the images at once. (Not to mention the musical complexity of Britten’s composition.) Of course, Jarman’s craftsmanship ensures that both are well matched and balanced, but this is still ultimately a demanding high-concept art film. In many ways it’s a feature length development of Abel Gance’s ‘Ode to the Sun’ sequences in J’accuse!, where the poet’s silent recitations are visualised through pioneering poetic montages. Jarman climaxes his film with a particularly troubling sequence of authentic wartime footage from across the whole twentieth century, sparing the viewer none of the horrific details. War Requiem is very much the kind of film that Gance was making a case for seventy years earlier.

The Officer’s Ward (François Dupeyron, 2001)

In a conflict as all-encompassing as the First World War, it’s hardly surprising that the national governments of all the belligerents would pursue the utmost discretion about any unfavourable consequences – not just heavy defeats, but also executions, mutinies and high casualty rates. Although it was standard practice that every soldier killed or missing in action was reported to the public (at least in the UK), any further details deemed harmful to national morale were withheld as far as possible. Aside from anecdotal evidence from veterans, the revelation of these details to the public, let alone official admission from the government, were shamefully belated.

If Uomini Contro exposed the suppressed truths of mutiny in the Italian army, then it would take even longer for knowledge of the treatment and recovery of wounded and psychologically damaged soldiers to enter the public consciousness. In the 1990s, Pat Barker’s popular Regeneration novels studied the realities of shellshock treatment, revealing that the supposedly calming effects of ‘retreat’ in isolated country hospitals in fact performed the double function of keeping the traumatised and disfigured away from the public at large.

This isolation is the setting for The Officer’s Ward. The protagonist Adrien is severely injured at the outset of the war; the scene in which his regiment is hit by artillery fire takes place on a green virgin landscape, long before the mudbath stalemates of trench warfare. Dazed, he asks, “Has the war started?” “The war’s over for you,” comes the reply.

The director’s most affecting strategy is to film Adrien’s journey from the field hospital to his eventual home for the next four years with complete subjectivity. The camera takes his perspective, picking up every repulsed reaction from overstretched orderlies and ambulance drivers, yet withholding the nature of his injury. He doesn’t yet know, so neither do we. It’s a technique half-borrowed from Elem Klimov’s extremely disturbing Come And See, a film about the Russian resistance to Nazi advances during the 1940s in which the soundtrack becomes muffled and swamped with a piercing high frequency tone after a shell lands so near to the protagonist that it temporarily robs him of his hearing. While Dupeyron’s film is a much more modest affair, the subjective effect still conveys a sense of helplessness and mortality. Through Adrien’s eyes, we absorb the trauma of an incomprehensible situation.

As he slowly recovers, the war is fought far beyond the enormous bay windows of the officers’ ward. Watching the film for the second time I came to recognise that it’s almost as much a story of the doggedness of the medical personnel as the suffering of wounded soldiers. It’s worth remembering that the most profound developments in reconstructive surgery were motivated by the demands of patients like these, and carried out by gifted doctors with an eye to the future. That such hope of advancement was possible in those catastrophic times is certainly a testament to something, though I daren’t venture to suggest what.

The Officer’s Ward is a much more conventional performance-led film than many of the other’s I’ve covered here. Looking back through them I can see the ground covered has been pretty vast, in both stylistic and historical terms. No true summary is possible, and there is far more to see. (By all means, start with the canonical classics I’ve been deliberately avoiding.) Still I regret being unable to track down such films as The Long Way Home, a 2013 Turkish drama about Gallipoli; Moon Sound, about the Russian navy; and Tell England, a 1931 British production directed by Anthony Asquith. Around the time I began researching for this article, I discovered that a huge First World War cinematic retrospective had been curated at the MoMA in New York, and I urge any interested readers to seek out the programme for future reference. If nothing else, I hope this disparate collection can pique a little interest in these popularly unsung films. On the occasion of the centenary, it’s worth taking stock of as many perspectives as possible. The war itself may now be outside of living memory, but cinema is capable of bringing it closest to our reach.