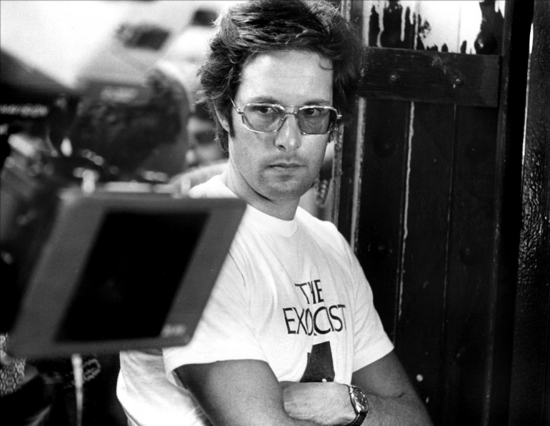

When I spoke to William Friedkin back in May 1998, he was promoting the UK re-release of his 1973 horror landmark The Exorcist, though we also conversed freely about other seminal films from his illustrious multi-decade career, such as The French Connection (1971), Cruising (1980) and To Live And Die In LA (1985).

Next week the 76-year-old director returns to cinema screens in style with Killer Joe, starring Matthew McConaughey, Emile Hirsch, Gina Gershon and Juno Temple.

Adapted from Tracy Letts’ play, this ultra-noir comedy thriller is an alluringly disagreeable sliver of hardcore Texas intemperance. McConaughey is in particularly fine derisive form as the titular Joe, a West Dallas detective who operates a profitable secondary occupation as a hired assassin.

I saw The Exorcist again the other day and it was just as chilling as it was the first time I saw it.

William Friedkin: Snuck in the first time round?

Yeah.

WF: I agree with you that it has lost none of its power. It’s just an extraordinary story that continues to hold.

I was wondering what do you think, personally, is the key to the public’s continuing fascination with the film?

WF: First of all, it deals with something that is never out of our minds – the whole concept of good and evil. Is there a palpable force of evil in the world? Does it manifest itself in individuals And if so, is there a force for good out there as well? So, that’s a universal subject that has occupied writers and painters and people of various artistic disciplines and religious disciplines since time immemorial. The Exorcist brings it right down into modern times. This is not a film set in Biblical times, or in the ancient days, or 18th century New England where they burned witches at the stake. It’s set in the contemporary world. It’s very realistic and yet it is about inexplicable things, that we all think about and affect us all the time. I think The Exorcist, even though it’s been ripped off by a lot of very second rate ideas over the years, it continues to make its presence felt because it takes those things seriously.

The Exorcist makes the practices of modern medicine look really archaic. Was that a point you wanted to make?

WF: Well, it says that modern medicine and modern science – which have supplanted religion in terms of, shall we say, a cure for what ails us – still have their limitations when it comes to certain inexplicable things. You can seek out modern medicine for what is tangible, but what is intangible and tragic are not answered by modern medicine. There is no answer.

Looking at the picture today, it’s refreshing that the pacing is so measured.

WF: It’s like that with a lot of films of the ’70s, Ian. The Godfather, of course, being an example of a film that moves slowly but inexorably. That wouldn’t be allowed to be made today. What they are calling ‘the great films’ of Hollywood in the ’70s, I don’t think they would have anywhere near the same effect today. Audiences have been conditioned by MTV. The kind of action films that everyone seems to want to see, to get it fast. An exception to that is Titanic, but it’s the exception that proves the rule.

Things aren’t made immediately obvious in The Exorcist. The audience has to do some work.

WF: Yes, that’s something I think is very important about the film. All of the answers aren’t there. I’ve found over the years, I’ve said this before, what people bring to the film is what they take from it. If you think of the world as a dark and evil place, unrelieved by anything else, that’s what you take from the film. If you think, on the other hand, that there is hope, and that hope and salvation are to be found, you take that from the film.

Are you a religious man?

WF: Very definitely. Not in a secular way. I don’t think that any one religion has the answer in preference to the others. I think there is a lot of good inherent in all of them. I just don’t think one has the answer exclusive of any other.

Is it true that you fired a gun on set to get a reaction from certain actors?

WF: Never with bullets, just blanks. That is something that has been done by film directors for years, before I came on the scene. I remember reading about it when I was just starting out. There was an article in Life magazine about George Stevens doing it on the set of The Diary Of Ann Frank, to get a reaction from people in this house that there was a Nazi occupation. It is very difficult to ask actors in film technique to go from a dead start and to create surprise or fear or shock. It’s very difficult. Most often it looks corny or unbelievable or like overacting. So as a film director you will utilise certain techniques to simulate the actions… that are real. It was overstated in the documentary [Mark Kermode’s 1998 TV doc The Fear Of God: 25 Years Of The Exorcist]. They make much too much of it, naturally, because it sticks out like a sore thumb, so a lot of people ask me about it.

What do you think of Mark Kermode’s theory, in his pretty exhaustive guide to the movie, that The Exorcist was mirroring the breakdown of the nuclear family and the struggles within America during that period?

WF: All of that is after the fact. None of it was intended, I can tell you. All we intended to do was to tell the story. What implications that may or may not have had, I for one was oblivious to.

The sound is fantastic on the print that I saw recently. What was the process you went through to produce that?

WF: There were a lot of different processes and a lot of trial and error. I was always of course influenced by radio drama. When I was growing up in Chicago, before television had any impact we still listened to radio. It would conjure up entire worlds just through the use of the human voice. So I have always approached the soundtracks to my films as a separate entity and quite apart from, and unique from, the filming process itself. There were a lot of things that were trial and error on The Exorcist to produce that track. I didn’t have it totally in mind at the outset, and I had a lot of inspiration come to me during the making of the track that went into it.

Were there any unusual methods used?

WF: Are talking about the stuff I did with Mercedes McCambridge [the voice of the demon]?

Yes.

WF: Well, yeah. I don’t think that has ever been done before or since. I took her, tied her to a chair, put her through various painful things, including drinking alcohol and eating raw eggs and stuff like that, to produce this sound. But it was stuff that she [McCambridge] understood and wanted to deal with, because she knew that a lot of what she was doing had to be unconscious.

Do you think your classic 1985 film, To Live And Die In LA, will get a similar re-release treatment to The Exorcist? Was it overlooked a little at the time of its original release?

WF: I don’t recall. I know it got a lot of attention over here and in other countries. I know it won a lot of film festivals, film noir festivals and whatever. I think it’s a damn good film.

The themes within that movie recur in a lot of your work. The highly ambiguous relationship between William Petersen’s driven secret service agent and Willem Defoe’s counterfeiter villain…

WF: The most important theme in my films is the thin line between good and evil. The fact that, very often, there are equal parts of both in all the characters, which is what I encounter in life. I don’t know anyone who is all good, or all evil.

Do you think that was an aspect of your work that was overlooked in Cruising?

WF: I don’t know if it was the same in England, but it was a national scandal [in America]. But what’s happened, curiously, is a lot of the gay organisations that at the time denounced the film, now praise it. And very often, gay publications that denounced it when it was released, give it a four star review and say, ‘Well, you might not like it, but this is the way things were for a certain segment of the gay population.’ It may be the last time things were like that.

Would you make a film like that again?

WF: What do you mean "like that"?

Well, so confrontational and…

WF: It’s a very unique picture, Ian. I was not trying to make a statement about gay life at all. I was just using a certain segment of gay society as a background for a murder mystery. It was an exotic background. It was the kind of scene that most people were unable or unwilling to look at. It was going on right in the underbelly of New York, as well as elsewhere, where there were a great many murders.

In that scene?

WF: Yes, in that environment. A friend of mine who was a cop, an undercover cop, who was involved with The French Connection case, had the same sort of situation that Pacino had [in the movie]. It was really his story. He told me about his encounters and his reactions to it, which I put into the film.

It must have been incredibly difficult to do that. He was straight, the cop?

WF: It was very disturbing for him, there was no question about it. It affected him in ways he was not really prepared for. It’s affected him even to this day. I still see him. He’s just recently retired from the department.

Could you tell me about Rampage [made in 1987 but unreleased in the US until 1992]? I don’t think that was given a proper release in the UK at all.

WF: Rampage is probably the most realistic and most disturbing film I’ve ever made. It’s kind of an examination of the death penalty, again using an actual case and the change of feelings within one of the major characters, who is a district attorney, about prosecuting the death penalty. I have a feeling that Rampage will be a revelation to a lot of people.

In a number of your films the police feature prominently. Where does your interest in that world come from?

WF: Well, my uncle was a cop. I used to hang around him and his cronies and I used to hear stories about what it was like to be a cop in Chicago in the 1930s. Guys like Capone were still around. My uncle dealt with these kinds of people. So I had an entrée to that world. I was, of course, fascinated by it and terrified to a great extent by it. So I maintained that interest. Most of my films, in one way or another, deal with the thin line between good and evil, the thin line between cop and the bad guy.

The Popeye character in The French Connection is a good example.

WF: Yeah, he is of course the guy with the badge, but in many ways he is just as bad as the dope smuggler.

He breaks nearly as many rules and laws.

WF: Yeah. The smuggler is a gentleman: he’s well dressed, he’s respectful to women, especially his wife. He’s a gourmet, has fine tastes and he’s otherwise a decent guy. But he’s a guy who is smuggling millions of dollars of heroin, with no conscience whatsoever. Whereas the cop – the guy with the badge – brutalises women and brutalises the public. He doesn’t really care about the public’s safety and he steps outside the law. Those characters are real. I didn’t make them up.

Do you find that it’s more difficult to make films that you really want to make today? Studios thinking that audiences have to be spoon-fed every detail of plots and so forth.

WF: To that extent, yes. I’m working on six different films now at the same time. And my approach is the same as it always has been, and of course it’s very much against the grain today. It was with the grain in the ’70s but, yes, audiences want to be spoon-fed today and I find it difficult to do that. I don’t make films for the lowest common intelligence. I really respect the intelligence of audiences. I think, for the most part, they are ahead of every filmmaker working today. But there are some of us who keep on doing what we do because it’s all we know.

Whatever happened after Star Wars obviously changed the face of cinema. The massive repercussions of that seem to be reverberating on and on.

WF: I think you’re right. The reverberations from that are still going on. I think you put it very well: spoon-feeding the audience, giving them stuff that they are very familiar with and where everything is clear from the outset. I prefer films that are more ambiguous, where there is no ultimate answer and the audience has to think through the meaning of the film.

Killer Joe opens on June 29 in the UK. Check back then for tQ’s verdict.