When watching dramas that follow the fallout of a nuclear attack, one thing is abundantly clear: that adult life as we know it is finished and reduced to the very basics of survival. Food, drink and avoiding sickness are constants and, in a sense, adults become children once more, muddling around in the ruins. With this in mind, addressing such concerns through a film made in a style more akin to a Sunday afternoon pastime for kids, as in Jimmy T. Murakami’s When The Wind Blows (1986), makes far more sense than it first appears. Based on the controversial picture book by Raymond Briggs, the film arguably gets under the skin more than most other examples addressing similar themes.

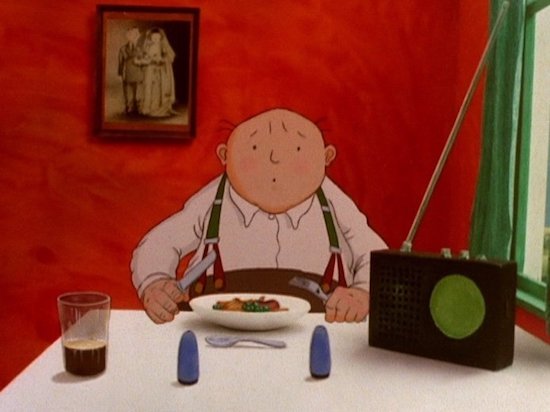

Though opening with real footage of Cold War era panic (soundtracked by the vocals of David Bowie no less), the film quickly shifts to animation; a mixture of real model photography work and superimposed pencil animations. It follows the lives of an ordinary retired couple, Jim (voiced by John Mills) and Hilda (Peggy Ashcroft), as they begin preparations for a nuclear attack they have been warned about whilst listening to Radio 4. Jim follows the public manuals on what to do – including the famous Protect and Survive government manual – building an indoor shelter and gathering supplies before the bomb strikes. Highlighting the slow and gentle ways of the couple then gives way to watching them slowly perish of radiation sickness after they survive the attack.

Such a bleak narrative renders the animation (and the original picture book form) seemingly unusual but both are incredibly deliberate and effective ploys. The characters are already innocent and naive – in fact so naive that even with all of their hang-ups regarding the Second World War (Stalin was "like an Uncle…" and you "knew where you stood" with him, Churchill, and Roosevelt), it’s impossible not to like them. They’re seemingly almost every post-war grandparent condensed into one couple: Hilda is more concerned about the curtains and the varnish as Jim makes a mess building their bomb shelter, the oven being on is a bigger worry even with the three minute impact warning, whilst Britain’s secret security service is apparently "EMI-5". It reminds in one sense of Powell & Pressburger’s The Life And Death Of Colonel Blimp (1943) in that war has moved on, leaving those with previous experience totally outdated. Here, the generation that outdated Blimp are now unaware themselves, nostalgic about the Blitz and their old air-raid shelters. Jim even walks after the ghost of Field Marshall Montgomery in one scene.

It’s this naivety, aided by the animation style, that makes the film so powerful. As statement upon statement of innocence builds, the pathos becomes almost unbearable. Jim will just "nip down to the chemist" the day after the bomb has hit to get some pills or go to "old Sponge’s" store to get some rat repellent; of course Sponge’s will be open, he wouldn’t miss a day’s trade. The fact that the characters continue on in this vein, even after the blast wave has disintegrated their house and left the countryside around them a barren wasteland, turns the film into an incredibly affecting work. It creates the same feeling as Dianne Jackson’s pair of short animations, The Snowman (1982) and Granpa (1989), the former being adapted again from a Briggs picture book and supervised by Murakami too. As in these shorts, something is smuggled in through the animation technique, something warming that builds connections to characters quickly, meaning that even the slightest hint of melancholy – a friend melting back into snow, an old relative passing away -–becomes surprisingly powerful.

This is never more apparent than in the portrayal of the blast itself. It takes Jim several attempts to convince Hilda to take shelter without her trying to first collect the washing in. They dive under their make-shift wooden shelter before a quick flash. The world is then turned sepia as the wave ravages through everything.

If this was a typical nuclear drama, the film would have made do with simply showing the scale of the devastation. The bigger the impact, the bigger the despair. But, as soon as this aspect of the destruction has been given some screen time, we move to something more personal: the destruction of a simple wedding photograph on the couple’s wall.

The film segues into a history of this photo, allowing for some of the couple’s backstory to be told, from their first meeting to their marriage in a country church. The blast then throws some crockery at the picture which smashes and falls to the floor. The point being that, in spite of still showing the scale of the blast, it hints that each object destroyed, no matter how trivial, also represented an infinitely variable sense of life. The destruction is not simply on a surface level but on a temporal level. The past may as well be wiped out when the bomb hits. Jim and Hilda survive to see the first few days of year zero.

So many dramas that deal with nuclear fallout present characters who are all too aware of what is going on around them. There’s no escape from the brutal, evolving totalitarianism of Mick Jackson’s adaptation of Barry Hines’ Threads (1984) or of Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1965), both of which build their drama by following the aftermath of the bomb primarily (but not totally) from a vast perspective. Even when such oncoming tragedies are played for darkly comic reasons, as in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb (1964), the characters are still aware of the absurdity and horror of their situation and, more importantly, are aware of what will be lost if just one bomb lands. Here, Briggs and Murakami take a refreshingly different path.

Heightened through the animation, a sense that Jim and Hilda still believe that their cosy village life can continue is the most heartbreaking of responses to what is still a worryingly tangible threat today.

When the Wind Blows, Dual Format Edition, is available now from the BFI