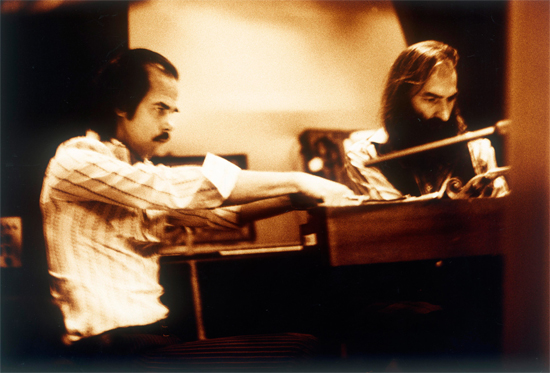

The past few years have been fruitful for the creative partnership of Nick Cave and Warren Ellis. There is, of course, The Bad Seeds’ return to highly sexed/undersexed, sonic grouching in Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! and the superlative Grinderman , who are expected to release their second album later this year. In the background of all this, though, has been Cave and Ellis’ collaboration on soundtracks for film, theatre and documentaries. In many ways, their work for cinema – collected on last year’s White Lunar – is a fascinating counterpoint to the music they produce for their two bands. Occasionally they seem to inform each other, the dark hums and dissolute vocals on much of The Proposition echoing moments on both Grinderman and Dig. The Proposition soundtrack, written for John Hillcoat’s 2005 "Australian western" stands up as an album on its own right, while the fragmentary pieces for the same director’s current adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road are both more startling (for the notorious basement meat locker scene) and, at times, perhaps resembling a more traditional film score. We began by asking Ellis whether he was a fan of the original novel, and Cormac McCarthy.

"Very much so. I’ve read most of his books, Blood Meridian being my favourite. I had also read the script before we started work on the film."

Did you work from a final cut of the film, or rushes?

We never work to a final cut. In the case ofThe Road,we saw several different cuts which varied greatly. John Hillcoat had strong idea about placement and style, and we worked with our regular editor Gerard Mccan. As the music is often improvised it tends to be rather flexible and moves with the changes made to the film. In all the films we have worked on, editing has gone on way past the date we finish the music.

Were there any parts of The Road soundtrack that proved problematic in this way?

We were constantly trying to hold the music back, keep it minimal and simple, light and not overloading the scenes. There were probably issues but I feel happy with the result. It just seems to be part of the whole process of making a film

The piano refrain bears a resemblance to Moonlight Sonata, and recurs throughout the film. Was it intended to act as leitmotif for the absence of the wife?

We never discussed Moonlight Sonata, honestly, but now you mention there is something there, although ours lacks the tension and resolve in that piece. Its emotional arc is very different to ours. I never saw it in that way, it seemed more a theme which related to the journey and the father and son. But the film is soaked in the mother’s absence and resonates throughout.

Your soundtracks often work in pieces of music in their own right. Is that something you’re conscious of when you’re creating them?

That’s a big part of releasing all the soundtracks that we do, Nick and I have to feel that they have to stand up on their own. They’re not just incidental music from a film. A lot of soundtracks can be very disappointing if you buy them, there’s only one or two pieces that you remember and are actually any good, and the rest just feel as if they’ve lifted it off the film and put it on… it’s kind of cheeky in a way, they just stick on some incidental music that sounds as if it’s from a cartoon. It can be very generic. Our music is done in a very different kind of way, it’s never spotted to moments in the film, we don’t make 15 seconds of a certain kind of music for a certain moment, they’re always fully realised pieces. We end up with completed pieces that have a start, a middle and an end. They feel in many ways like their own statement.

Soundtracks replacing the classical repertoire on radio, and they do sound strangely dislocated outside the original cinematic context

You get that in films. A lot of the times when you listen to it it’s as if anything could have been chucked in there, it seems incredibly arbitrary. It’s seems ‘oh give us some spooking music, Jake’ and away they go. In a way ours is different because we come from a different background, I’ve worked in an instrumental band for a very long time and it’s always felt to me like a very different… with Dirty Three for instance we’ve never gone out there just to make mood music, there’s been a sense of purpose involved in what we’re doing, there’s been a narrative. The Bad Seeds too, Nick obviously has a thing going on with his words, and the Bad Seeds as a band has always been about the music as well, what sort of moods it creates in serving the song.

So how do you put a soundtrack together?

It’s like when we go in for Grinderman, we sit down and make slabs and slabs of music, just keep recording and come out with sometimes five or six CD of music. Then we start with an editor sitting down and putting it into the film. I’d say 80% of it is very improvised and organic. The Proposition was a thing that seemed to find itself, and it was amazing to see that unfold. Large slabs of those tunes were just put in on cues on those films and they just worked, the length that they were was just what we played. It’s interesting, you stick it onto an image and you see how it has a very different effect from if you have like a cymbal crash when a door closes, to give you something very obvious, as opposed to something that’s not exactly in sync with the thing that ‘s going on, but that might pre-empt it or come afterwards. It’s the difference between a singer singing on the beat or behind the beat to push the band along, like Billie Holiday, to push the band along and make them appear more on their toes – it’s because she’s singing behind. Putting music to film can have that effect too, it can either delay the images or can push them along and give them momentum in a way that you hadn’t even anticipated. Our approach is very different from that spotting that people traditionally do with films, when they do it to image. We work to image, but very vaguely. It’s very loose.

Do you find yourself playing differently? Have you learned new things

I guess so yeah. I think the big general difference with the film stuff is you’re doing something for someone else, you’re serving something else, not your own desires and your own needs. But with a film you’re accountable to the director and producers and they’re all putting their opinion in. In many ways if you think it’s really good but they don’t like it, well that’s where the buck stops. The great discovery I’ve had is how liberating it is to have somebody telling you to do something again, particularly with the results we go with Jesse James, it ended up being something much better than we would have got in the first place.

Was that difficult at first?

Yeah it was. We thought the music we went in and made was really great, then Andrew said ‘Look, I like this tune but the rest doesn’t do anything for me’. We were pretty indignant. We went back in again, and the score that we have now is infinitely better than what we had before. It was really interesting. There was a period of time that was really hard funding that, but all those things when you get through that, that’s when the payoff happens. That’s one of the strongest memories I have of doing that stuff.

Is there a different dialogue doing this from in Grinderman or the Bad Seeds where you and Nick Can change things more easily?

Grinderman’s a bit different, Nick and I converse about that really regularly and really closely. A long time beforehand we talk about what we’re going to do.

Do you approach the documentaries differently to the films?

No the main difference with the documentaries is that they are in most cases, in any documentary I’ve seen about people, the dialogue drives it along, so the music has to be really inobstrusive. In films too the music shouldn’t be scene stealing, unless you need the music to take over, or assist a piece of performance to add some emotional pull or humour. I think with documentaries there’s a lot of dialogue, and it’s very easy to make them sappy and saccharine. The Road has more in common with the dialogues than the other two films. The Road has that thing that we’re always aware of where the story is so loaded, and so emotionally charged that you stick a weedy violin on top of that and people will say ‘get out of here’.

That was something we fought to keep, not from the financiers, we fought to keep that in there. The stories about that film would make your hair go grey. I think the film world is very different. The term ‘artistic control’ is in a room separate to anything else. The more money that’s spent on it the less control you have, the more people trying to get their point of view in. If you’re stuck with a terrible producer, you’re in real trouble. They have one shot with the film for it to work in most cases, there are exceptions, the ones that creep up and take off after a while, but a record you put it out there and if it doesn’t work in the first week or so you can forget about it. They have to get it right, so there’s all these test screenings and stuff, I was never really interested in that world at all. I couldn’t work in that world at all. When there’s more money involved there’s more pressure on you to do things that you don’t want to do.

The first time I worked on a film I was mortified. There was a producer’s meeting with the director, and they got involved, ‘why is this so long, people are going to fall asleep, get rid of it’. The fact that the director will have a vision, and then everyone else has a different one to that.

People like picking bits off?

Yeah. I don’t know, what a fucked up world! They’re different kind of people in the film world. I had some experience in the advertising world, and that was very surreal.

Are you surprised by the demand there’s been for your soundtracks?

We only work with people we know and whose visions we respect. The stuff we’ve knocked back because A it doesn’t seem appropriate or B we haven’t had time, it’s not like we do everything that comes our way. Because we’ve known John for years it’s not like we’re expecting him to ask to do it. I guess I’d be more surprised if Spielberg or someone like that called up, someone outside that circle. In some ways it doesn’t feel so alien doing some of the things we have. I guess we go in the studio and do our stuff. We have some kind of discussion with directors, but we’re really removed from that whole thing. You do your job and that’s it. If they say ‘well we want to get Sting on this song’ and we say ‘well we don’t want Sting on our song, we want our music back’ they’ll say ‘well we own it, we can get any fucking cunt we want to sing on it’. Once you’ve done it, that’s the end of the story in a way. You’re just part of the machine.