"Y’know, they say that dreams are real only as long as they last. Couldn’t you say the same thing about life?"

Waking Life, 2001

By the turn of the millennium, Richard Linklater was the uncrowned king of the ‘hangout movie’ – a stripe of cinema in which plot and momentum play second fiddle to the business of leading the viewer among quirky, comical or loquacious characters, just for the pleasure of hearing them think out loud.

Through the casual conduit of the director’s largely handheld camera, viewers were able to mingle with, and eavesdrop upon, the alt-culture dropouts of Slacker (1991), the Led Zep-worshipping stoners of Dazed and Confused (1993), the nascent, Franco-American romance of Before Sunrise (1995) and the disillusioned denizens of an Austin corner store in SubUrbia (1997) – a darker effort scripted with Mamet-like bite by fiery stand-up Eric Bogosian. Indeed, with his freewheeling taste for lo-fi visuals and naturalistic dialogue, pitching every scene somewhere between a wry aside and a deep-and-meaningful, there are solid grounds for enshrining Linklater as the godfather of mumblecore.

In 2001, though, something unexpected happened: Linklater became one of the most daring formal innovators of his generation. Now, thanks to Arrow Video, we have a chance to relive that singular surprise with the label’s reissue of his multi-coloured masterwork Waking Life. Revisiting the film with 15 years of perspective on what Linklater’s peers were up to at the time brings home how unique his achievement was. In the all-American saloon bar of fellow celluloid hangout merchants, the director’s closest contemporaries were Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, Cameron Crowe and Kevin Smith, all of whom were more at home with letting crack-squad ensemble casts chew the fat than tailoring their dialogue specifically to hit regimented ‘story beats’. Something else those directors had in common was that they’d acquired various cachets of authorial distinction, whether through their shot styles, or the flavour of their screenplays. But none of them had delivered a project anything like as experimental or idiosyncratic as Waking Life – and, what’s more, they still haven’t.

In its structure and tone, Waking Life is significantly more nonchalant than even the loosest moments of Linklater’s previous films, playing out as a series of vignettes or playlets mostly featuring a nameless man in his early twenties (Wiley Wiggins) strolling around Austin and chatting to experts in philosophy, language and consciousness about the state of their respective arts. Other scenes take the shape of debates between thinkers and artists about key areas of their disciplines, or straight-to-the-lens monologues delivered with mesmeric intimacy that almost drop the audience straight into Wiggins’ interviewing perspective.

None of the characters are introduced by name, and only a few of them are immediately recognisable for who they are: filmmaker Steven Soderbergh, conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, the duo of Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, riffing on their Jesse and Céline roles from Before Sunrise, and Linklater himself. There is no dominant narrative arc, save for Wiggins’ growing uncertainty over whether he’s dreaming or awake, and as the talking-head experts are free to speak their brains in an unfiltered fashion, typically in uninterrupted, single shots, what we have is a curious creation that sits squarely upon the blurred line between fiction and documentary.

All of which is great. But it’s not the main attention grabber.

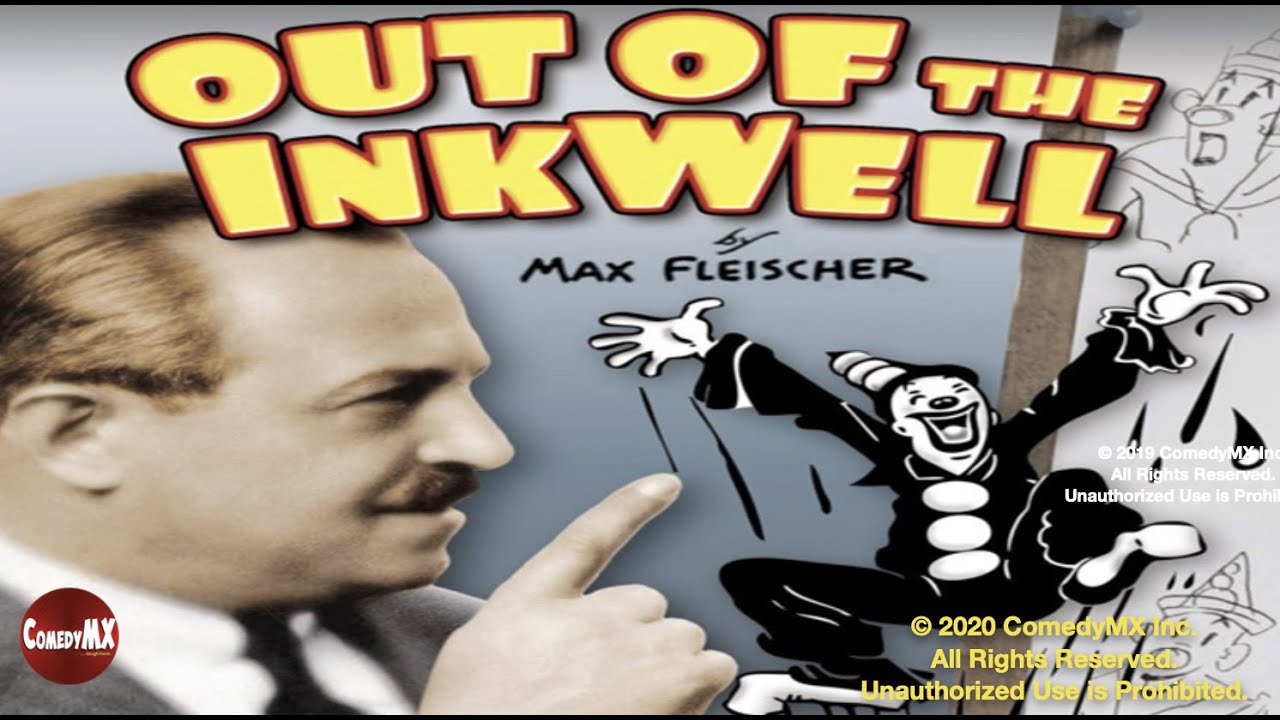

The attention grabber is that the entire film, from edge to edge, is coated in a thick, gloopy wash of gaudy, garish animation, overlaying original sequences shot on mini-DV. After Linklater had cut those scenes into the shape of the final release, the film was passed to a post-production team led by art director Bob Sabiston: a pioneer in the digital phase of the animation technique ‘rotoscoping’. In its earliest form, patented in 1917 by the ground-breaking Max Fleischer, rotoscoping consisted of live-action footage of actors in scripted scenarios being projected on to a lightbox, upon which an artist could pin sheets of paper and make frame-by-frame tracings of the actors’ poses – the point being that the resulting characters would be anatomically proportionate and capable of busting physically believable moves, all while retaining a fantastical allure.

As well as playing a key role in Fleischer’s landmark Out of the Inkwell series – which, presciently, used the technique to toy with the boundaries between animation and live action – rotoscoping was integral to his brother Dave’s Superman shorts of the 1940s and Disney’s original run of animated classics that began with Snow White (1937). Later, rotoscoping was used to buttress the brawny battles of Ralph Bakshi’s muscular The Lord of the Rings (1978), becoming in many ways a primal form of the mo-cap technology that Peter Jackson would deploy in his live-action take on the same, hefty tome.

In Waking Life, Linklater and Sabiston’s coup is to wield the far more fluid and flexible tool of digital rotoscoping in the name of abstraction – liberally visualising the conceptual patter of the film’s characters; or chiming with particular moods or noises on the soundtrack; or warping the Austin backdrop to reflect some of the speakers’ eccentricities; or achieving impossible camera moves – or simply screwing around with goofy humour for pure effect, as with one scene in which a lecturer is redrawn as a chimpanzee in a shirt and tie.

The outcome in aesthetic terms is that the film becomes a living Lichtenstein – a moment-by-moment, restless, throbbing, pulsing pop art installation that absorbs us in its speakers’ various riddles and witticisms by making us wonder what the lines and colours are going to do next. The outcome in meaning terms is that the film clinches a much higher degree of subjective identification with the characters’ mentalities than would have been possible with the unadorned, original shots – strongly echoing David Cronenberg’s credo, coined in this memorable Sight and Sound interview, that "all reality is virtual".

Waking Life is a veritable feast of transformations. A speaker on evolution is shown bending and bulging out of shape as he warms more and more to his theme. A politically jaded young man painlessly self-immolates on a desolate street, the animators whipping the conflagration into a vaulting tulip of puce flame. Two film theorists end their discussion on the merits of looser story structures by turning into a Magritte-like vista of people-shaped clouds. Rooms are routinely disrupted, their walls lurching fitfully out of place while items of furniture slip and sway across their floors. In every single shot involving an extensive depth of field, the parallax of the receding layers trembles nervously, the film banishing notions of concrete perspective by externalising the doubts we have about our own perceptions.

In other words, Waking Life is a film that constantly illustrates itself – the animation’s gouache-like surface a feedback-rich sounding board for the dialogue.

Tellingly, the penultimate scene features Linklater waxing lyrical on the elastic nature of time and touching on a paranoia-inducing anecdote about science-fiction author Philip K Dick. (In this apparently true story, Dick ran into a woman at a party who happened to have the same name as one of the characters in his novel Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said; what’s more, she was dating someone with the same name as her corresponding character’s boyfriend, and was having an affair with a man whose name matched that of another character in Dick’s book.) As well as spotlighting the film’s primary, philosophical influence, the scene foreshadows Linklater’s decision to repeat the rotoscoping experiment in his 2006 adaptation of the author’s sinister satire, A Scanner Darkly.

In that film, an Austin-based narcotics agent (Keanu Reeves) is hemmed into the excruciating position of having to report upon himself, after his undercover work leads him to become addicted to the epidemically powerful psychoactive drug, Substance D. Reunited with Sabiston, Linklater again uses the painterly medium of rotoscoping to challenge the framework of reality, hitting the audience with a parade of arresting visions as the drug takes hold on its various victims.

During the opening scene, long-term addict Charles Freck (Rory Cochrane) struggles with scraping a host of self-replicating bugs off his itching skin – bugs that aren’t actually there. Later, he is visited by a bulbous-skulled, trans-dimensional being with dozens of twitching eyes, who proceeds to read a litany of Freck’s misdemeanours from an endless scroll. And in one particularly jarring twist on the hangout scene, Reeves’ tweaked-out agent recoils in horror as D-heads Barris (Robert Downey Jr) and Luckman (Woody Harrelson) transform into giant cockroaches – Linklater amusingly allowing them to keep their famous faces. It’s in moments such as those that the advantages of rotoscoping really shine through. If that third scene, for example, had been etched in photoreal CG, viewers would have been subconsciously trying to judge how well the special effects were morphing Downey and Harrelson into man-sized insects. But because the animation wash minimises the amount of visual information, there’s less of a leap, and we just swallow it.

That gulf between Linklater’s experiments and the prevailing mode of animation favoured by the Hollywood mainstream is vast, and it’s worth taking a moment to consider what the major studios have sacrificed by leaving more playful approaches to the medium on the sidelines. While the industry standard of mo-capped skeletons draped in layers of hi-res, digital rendering has spawned a string of high-concept blockbusters in the years since Waking Life emerged – such as Robert Zemeckis’ CG trilogy of The Polar Express (2004), Beowulf (2007) and A Christmas Carol (2009), plus James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) and Steven Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin (2011) – it’s remarkable to what a colossal extent that technology has been geared towards pure spectacle; of creating fantasy characters exclusively for the space in front of the eyes, rather than exploring what lies behind them.

In fact, following Linklater’s rotoscoped duo, there’s only one other filmmaker who has tapped into animation’s potential in a comparable way: Israeli director Ari Folman. In his 2008 masterpiece Waltz with Bashir, Folman uses a tantalisingly similar narrative prop to that of Waking Life, tracing his own journey around Europe and the Middle East to interview old Army friends who served alongside him in the 1982 Lebanon War, hoping their recollections will help him overcome his (fictionalised) amnesia. Taking those central themes of forgetfulness and the psychological barriers that ex-soldiers build against their wartime experiences, Folman uses the imaginative scope of animation to ask what really happened in the war. Eventually, he comes around to acknowledge his complicity in the horrific massacre at Sabra and Shatila, where he acted as a night-time flare-lighter, enabling Israeli soldiers to pick their lethal way through a Palestinian refugee camp. Folman’s gradual, dreamlike realisation of that compromising truth is reflected in the inner journeys of his peers, many of whom fell prey to their own guilt-charged dreams and nightmares amid an already nightmarish event.

Following that bravura fusion of drama and documentary, Folman changed tack and moved on to the decidedly Dickian sci-fi of 2013’s The Congress, starring Robin Wright. In its parallel reality, Wright is a washed-up actress who submits to a process whereby her image is exhaustively scanned and her emotions harvested, allowing the all-powerful ‘Miramount’ studio to recycle and regurgitate her digital doppelganger in movies for generations to come. After the story jumps forward 20 years we learn that, in that time, Miramount has managed to synthesise addictive drugs from the personality data provided by its actors, enabling everyday people to ‘be’ their idols just by knocking back a phial. As she drives to a Miramount conference, Wright takes the drug based upon herself, and the world around her transforms into a nightmarish, animated caricature of the celebrity experience. Her journey out of that underworld occupies most of the rest of the film.

As critics marvel at Anomalisa – Charlie Kaufman’s queasy study of modern, existential dread thorough the medium of stop-motion puppets – the rerelease of Waking Life is a timely reminder of how animation that revels in its own artifice can get under the skin of characters and audiences in ways that more ostensibly ‘realist’ CG can’t. The film also proves that animators are capable of conjuring the very type of magic realism that many assume is the exclusive preserve of novelists. Just as importantly, it adds credence to Linklater’s status as a shrewd maverick. While his later studio comedies School of Rock and The Bad News Bears hardly hinted at award-winning potential, his desire to innovate was clearly coupled with a taste for the long game: the year after Waking Life was released, he began to shoot a film called Boyhood.

Waking Life is out on Arrow Video now

Matt Packer can be found on twitter at @mjpwriter