"See you next year, mate." It’s one of the very first lines of the film – and it’s pretty well guaranteed to get a laugh. A class of schoolchildren is dismissed. As the kids pass their teacher they say their goodbyes, wish him well for the holidays, hand him small gifts, and so forth. The last pupil to leave, considerably older than the rest, deeper voiced, nonchalantly says it: "See you next year, mate." It’s casual, obvious, friendly. Everyone in the screening room chuckles. But over the course of the next two hours, this "mate" will take on a sinister, oppressive aspect. Wake In Fright is a film – at least superficially – about the tyranny of mateyness; the imperative demand of the next round of drinks. And never have I seen so much beer guzzled and sloshed over a reel of celluloid.

Director Ted Kotcheff laughs heartily down the line from Mexico – and not for the last time – when I mention the number of pints drained throughout the film. "It’s a funny story actually," he insists. And, indeed, what tale involving so many gallons of West End Bitter isn’t?

"The very first day of shooting, Chips Rafferty –" a legendary Australian actor who plays policeman Jock Crawford in the film "– had to pour a whole pint of beer straight down his throat. We said: Action!" Kotcheff makes a disgusted spitting kind of noise. "What’s the matter Chips?" He said, "This beer – it’s not real beer!" I said, "Yeah it’s beer – it’s non-alcoholic beer."

"Non-alcoholic beer! I can’t act with non-alcoholic beer! I want real beer."

"Chips! I might do eight takes just on this one shot. You’re going to drink eight pints of beer?"

"He said, Ted, you provide the beer, I’ll provide the acting."

"And he did. It’s marvellous just to watch him. He doesn’t show the slightest degree – not one iota of inebriation. He never stumbled, never slurred. It was extraordinary. All the rest of the cast drank non-alcoholic beer."

The film’s story, based on a novel by Kenneth Cook, concerns a city-born school teacher, John Grant (played by Gary Bond), stuck working in a one-pub outpost deep in the bush. When the Christmas holidays roll around he hopes to get back to Sydney to see his girlfriend but ends up losing all his money on the toss of a coin and stuck in the mining town of Bundanyabba. There he meets an increasingly deranged cast of local characters, all of whom seem disturbingly keen to buy him a pint.

Kotcheff first became embroiled with the picture in 1969 when his friend, the writer Evan Jones (who he had just worked with on Two Gentlemen Sharing) suggested Kotcheff take a read of the novel he’d just been hired to adapt. "It’s right up your alley," Jones promised, " – a lost week in the outback!" Kotcheff immediately warmed to Cook’s book for its "intense atmosphere" and Jones put his friend’s name forward to the producers. Before he knew it, the director was on his way to Australia.

What he found when he got there was an environment strangely familiar from his upbringing in northern Canada. "The same vast empty spaces that paradoxically are not liberating but claustrophobic and imprisoning," he recalls. "I used to describe Canada as Australia on the rocks. Both had that hyper-masculine society."

From the very beginning, Wake In Fright recalls something of Sergio Leone’s slightly earlier Once Upon A Time In The West – in particular the wide open space of its opening scene, with its deftly composed collage of foley sounds. Kotcheff and Leone would become friends later, after sharing jury duties at Montreal’s Le Festival des Films du Monde in 1979, but the Canadian is loathe to admit any direct influence, nor, he claims, did he ever think of Wake In Fright as a western, despite what he calls its "frontier mentality – not dissimilar from what the people in the American west went through at the time."

Part of what links the two films, in my mind at least, is its easy, unhurried pace and heavy ambience – something aided immensely by British composer John Scott’s original music. Like Leone’s frequent collaborator, Ennio Morricone, Scott combines his orchestra with less obviously symphonic instruments like the guitar and Jew’s harp as well as the didgeridoo and clapsticks native to the locale. The vagaries of Wake In Fright‘s funding had compelled Kotcheff to seek out a British composer so he arranged for a screening of one of Scott’s earlier works and straightaway "loved the style of it. He had a tremendous amount of atmosphere." The pair would work together again on the American football picture North Dallas Forty before the composer went on to the likes of Amores Perros and The Limey.

If it starts off like a western, however, within about an hour its become a horror film, anticipating the night-for-night thrills of I Spit On Your Grave and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The goriest moment – and what Kotcheff calls the film’s "visual climax" – comes with its notoriously gruesome kangaroo hunt scene. A vegetarian himself, having once worked his way through college in a meat-packing house, Kotcheff was initially anxious about how to shoot this scene until one of the local crew members suggested a means of capturing the violence of the story without special fx and without causing the deaths of any marsupials. "You know Ted, they kill hundreds of kangaroos every night in the outback," he said.

"What?" replied the director, aghast.

"They have these big refrigerator trucks and six pairs of hunters go off in different directions and then bring back 15 or 20 and then put them in the refrigerator truck, behead them and skin them."

"What for?"

"Oh, well, they export them to the United States for the pet food industry."

So it came to pass that the squeamish Canadian found himself accompanying a bunch of hunters on a nightly spree. "It was horrendous," he says. "About half the footage was unusable. The audience would have run screaming out of the theatre." The worst of what Kotcheff witnessed came later in the night when the hunters started to lose their eye "so they were shooting them and not killing and they had to chase them down with a vehicle while the blood was pouring out of them, spurting out of their nostrils."

Kotcheff kept a representative of the Australian Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals with him at all times while he was shooting in order to make sure the film got their seal of approval. They were keen for him to use much gorier footage from the hunt than he did ("I said, ‘I can’t! I can’t! The audience will just run away!’"). Some fifteen years ago, the RSPCA called Kotcheff back to tell him that thanks to the horrors depicted in Wake In Fright, the Australian government had passed a law banning the practice.

But if the film has its moments of menace, it’s also a remarkably warm film. I get my biggest laugh out of Kotcheff when I tell him it reminded me of The Odd Couple, with Gary Bond replacing Jack Lemmon and Donald Pleasance in the Walter Matthau role. There’s more to Wake In Fright than some sort of über-Calvinist don’t-trust-your-friends parable. Indeed, if we are to take any message away after the final curtain, it may be the complete opposite. There’s no sarcasm in Grant’s voice when he describes his holiday in the ‘Yabba as the "best ever".

"That’s because it’s an odyssey of self-discovery on his part," Kotcheff explains. "He didn’t realise who he was, what he was capable of. In all my films there are people who don’t know themselves but they’re haunted by their lack of understanding about themselves and they put themselves into situations where they are almost driven to self-knowledge. I guess I’m always haunted in my own make-up: why did I do that? Why did I say that? What possessed me? And I think one of the mysteries of life, at least from my point of view, is that I don’t know myself. I think most people do not know themselves. They don’t know what they are capable of."

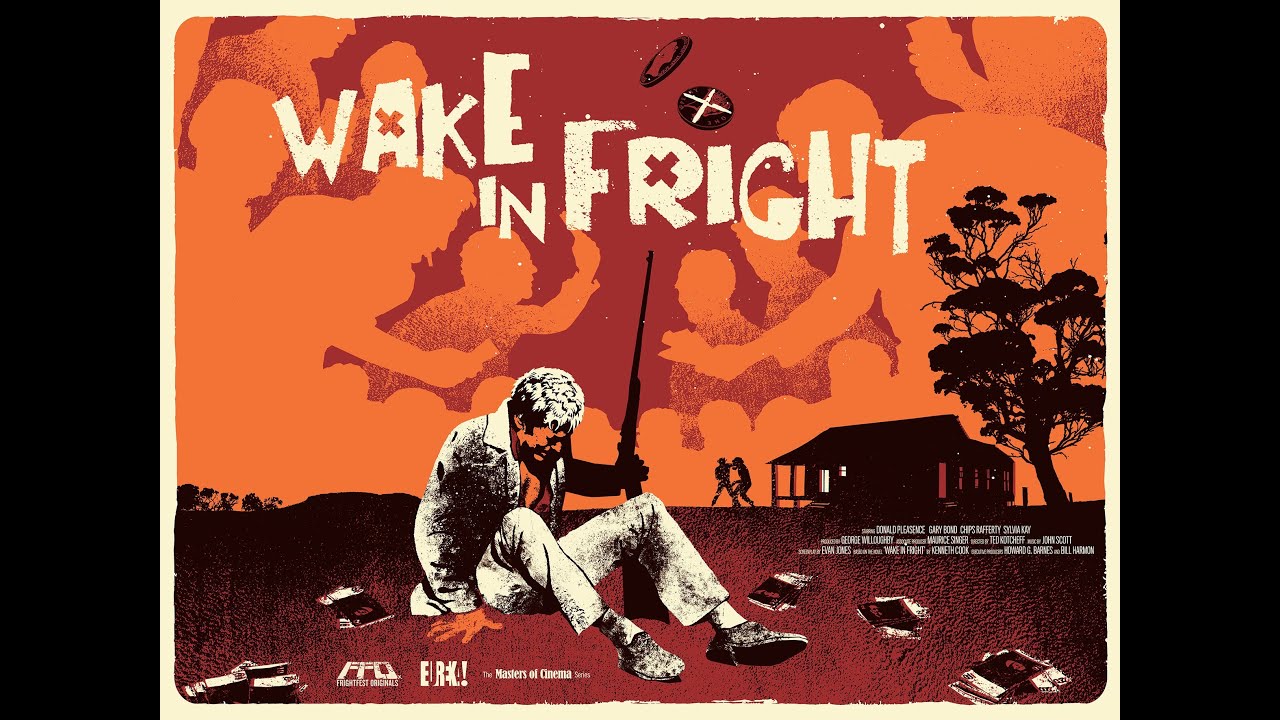

Wake In Fright is released on DVD and Blu-ray on March 31 via Eureka: Masters Of Cinema