W., while intermittently amusing, is not what it could or should have been. Since Oliver Stone rustled up his idiosyncratic, engrossing biopic of Nixon and the twitchy, paranoid, conspiracy-theory orgy that was JFK, he has had a career to save. No longer able to play the enfant terrible, expected now to have elder film-maker gravitas, he’s taken it upon himself to play safe, to play, shall we say, pro-American. Alexander, which was the last time he gave free rein to his artistic ego, was a terrible mess. So he made himself employable again with the dutiful, workmanlike, forelock-tugging World Trade Center. Even so, W. had to be financed via European and Chinese money, with no American studio prepared to go near it.

Let’s be frank: we all wanted this movie to kick the shit out of Bush. Rarely has a world leader been so openly mocked, pilloried, loathed. And sometimes the people doing the mocking, pillorying and loathing even know what they’re talking about. (Meanwhile, many of us know less about the critical nuances of world affairs than Sarah Palin, yet, being liberal media-devouring types, are glad to jump on the bandwagon. Because war is wrong and bad. Isn’t it?)

From a position of either wisdom or ignorance, it remains extraordinary that the (as I write) President of The United States Of America (who will, by the time this runs, be a lame duck not just factually but technically) found it somehow possible to blow all the sympathy and goodwill that poured towards America after what we are obliged to refer to as “the events of 9/11“. That took some doing, but do it he did, and then some.

There is a Shakespearean tragedy to be cleverly ripped off here but, frustratingly, Stone doesn’t get close to it. Instead he deals with surfaces, flitting between light comedy and broad farce. W. is a series of sketches that might just have made the cut at Saturday Night Live on a slow night. The impersonations – sorry, the acting performances – are very good. But the script, by Stanley (Wall Street) Weiser, winds up as just a tick-list of the greatest hits, the best-known moments of Bush idiocy, the fumbles, the stumbles. Bush is mildly lampooned, but never with the savagery our animal lust for revenge demands. You could argue that he even emerges from it all as a likeable buffoon. OK, it’s just a movie. But if it survives as a document which future generations refer to and enjoy, which is not impossible, then Stone may have done the modern-day equivalent of portraying Hitler as a pussycat. Without an iota of the style of Leni Reifenstahl.

Stone passes completely on 9/11, shockingly. Perhaps he feels he “did” that already in World Trade Center, but it was surely the moment sent to make or break Bush‘s story arc. And where’s New Orleans? He also tones down his usual peripatetic style, opting for a flat rhythm and tone. He bends over backwards to be fair. It’s as if he thinks he’s making one of those saccharine biopics about Ray Charles or Johnny Cash which have to be scrupulously kind, bordering on hagiography, because widows and relatives are alive and potentially litigious.

The film cuts back and forth between Bush as feckless young man and Bush as leader of the free world. It’s been suggested that it’s in the youthful Bush scenes that Stone fires his best shots, revealing the prodigal son as a selfish party animal. Bush drinks, smokes, plays sport and even on occasion – get this – dallies with consenting females. What a freaking weirdo! How could anybody like that be normal? God, it’s disgusting.

Eventually, turning forty, W. tries to please his dad – and the film is obsessed with this tenuously imagined Freudian/Oedipal streak – by entering politics, as he’s no good at business, or indeed working in general. Again, this notion – that he’s not practical-minded – may be intended to make him seem a dick, but awkwardly brings to mind… most great artists. There’s also a fudged suggestion that he “gets” religion but not quite. “The Decider” is commonly undecided.

Many of Calamity George’s set-pieces are present. The choking on a pretzel. The malapropisms and bungled catch-phrases. The baseball analogies. The signing off on torture. The cast of supporting villains. They just don’t gather momentum, purpose or wrath, and leave things hanging like a Florida chad. There’s a stab at a climax in which Bush is overcome by a descending cloud of guilt and dread, of almost-realisation of what a cock-up his hubris has made of things, and in fairness this is pretty good.

This is all sounding very damning of what’s not an atrocious film. That’s because the subject was so meaty and loaded with potential for a great Oliver Stone film: expectations were high. There could have been a glorious Bush-baiting piece, perhaps a comedy drawing on the more acidic tones of Steve Colbert and John Stewart and Tina Fey, but that won’t happen now because this has taken the pitch. W. is affable yet inconsequential, its punches pulled, something like Mike Nicholls’ Primary Colours.

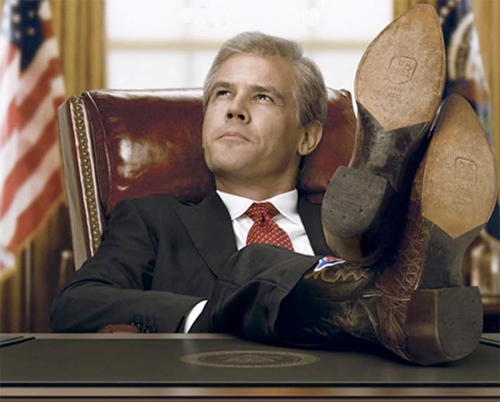

Praise must, however, be doled out to the cast. Josh Brolin gives a terrific turn as Bush both in youth and in his version of maturity. James Cromwell is wry and dry as Bush Senior, while the baddies – Richard Dreyfuss as Dick Cheney (explaining the Middle East/oil scenario more lucidly than any newsreader), Toby Jones as Karl Rove – are shrewdly pitched just on the brink of panto. It has to be added that Thandie Newton is comically bad as Condoleeza Rice, portraying one of the world’s most powerful women as a simpering moon-eyed ninny in thrall to W.’s every confused grunt. Jeffrey Wright does his best to exonerate Colin Powell from all blame, while Ioan Gryfudd’s brief cameo as Tony Blair is almost as close to the definition of rabbit-caught-in-headlights as the man himself.

As the movie, having made its cheap-gag check-list, finally strives to shoehorn in a pinch of seriousness and due diligence towards the end, Bush is asked by a reporter what place he will have in history. “In history…”, he mutters, “we’ll all be dead.” And he is not being an existential poet here. He is just being a bit lost, a bit clueless. A bit powerless. Oh the irony. Similarly, the dream ticket of dissenting director and sinning, supercilious subject here vaporises somewhat, unsure of its theme, its motivation. W. gives us only some of the what and none of the why.