Now a boutique condo offering sky-high flats at sky-high prices, 110 3rd Avenue was once a shady retreat for the flesh fiends of New York City. It was here, on the lowest rung of the Lower East Side, the Variety theatre stood small and shone bright, screening blue movies before VHS hijacked the market. But what was surely a glaring eyesore for passersby, proved an inspiration for Bette Gordon. “Its marquee was like something out of the past,” she told Whitehot Magazine, “I couldn’t stop looking.” It was as if a tacky neon lightbulb went off in her head, one that the filmmaker had been waiting nearly a decade for.

The result, Variety (1983), serves a clever culmination of the bold ideas typifying much of Gordon’s early shorts, exploring the politics of desire and the struggle of women to define themselves in male-coded spaces. Bette Gordon’s New York isn’t exactly Broadway and bagels, but a dizzying tour of sex shops, dive bars, and – if you get peckish – an early-hours fish market. Though, while Variety may model itself on the film noir tradition of shadows and sleuths, it manages to rewrite the playbook entirely. Gordon disrupts genre convention by perverting classical narrative functions. Here, by making a woman the investigator and a man the femme fatale, the director – as she puts it – “reverses the look” of power, radically re-defining onscreen femininity in the process.

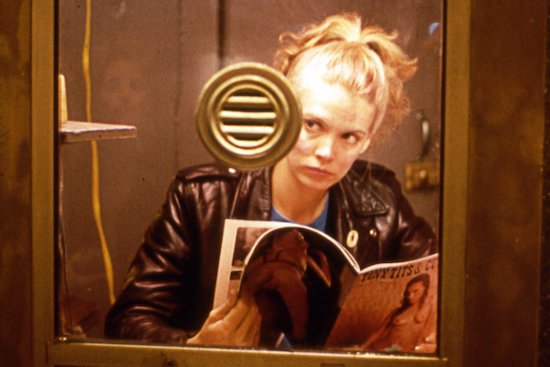

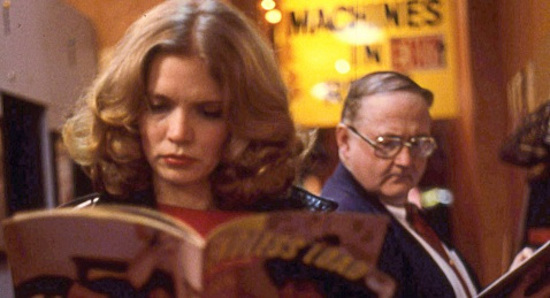

It’s aspiring writer Christine (Sandy McLeod) who eventually gets caught up in this crossfire of looks. Eager to find any job that might pay the bills, she takes up selling tickets at the Variety. Her street-side booth, which at first appears to frame her like a zoo animal, soon becomes a lens out onto a netherworld of trench coated oglers and shady suits. Sticking out from the crowd, however, is Louie (Richard M. Davidson), dapperly dressed and remarkably confident for a guy who spends his lunch-breaks at a porno fleapit. He asks Christine out, and she’s intrigued at first. Though when he abruptly dashes off mid-date, her curiosity turns to fascination. She decides to trail him across the city as he attends sketchy, late-night appointments, making deals and shaking hands. Is he a Mafioso? A pimp? A smuggler? Or all the above? Christine isn’t sure, but she’s determined to see just how deep the rabbit hole goes.

As New York’s latest gumshoe digs for details, the borders of fiction and reality become increasingly blurred. Soon fantasy reaches full bloom. Christine’s sexual daydreams of Louie start to magically project themselves onto the theatre’s screen – a sequence which film scholar Joan Hawkins credits to Gordon’s ability to “carve out roles for female agency and pleasure in even the most masculinist of genres”. Sure, Christine may be a struggling writer in a dead-end job, but from here our heroine writes her own narrative. She becomes a creator in control of her voice, and so in command of her public image, that by the film’s end she appears leather-bound, leonine, and dangerously low on patience. When she finally picks up the phone to confront Louie, he agrees to meet her. But instead of the climactic showdown we’ve come to anticipate, audiences are left with a narrative ellipsis: the image of a dark, deserted street corner – a shot that, for Gordon, cutely exhibits “the empty space between desire and gratification.”

This interplay between dark desires and even darker environments is one the director openly attributes to the golden years of film noir, citing Samuel Fuller and Jules Dassin as key influences. Yet it’s Alfred Hitchcock who arguably looms the largest, so much so that LA Weekly dubbed Variety “a feminist Vertigo” upon release. It’s a moniker which has certainly stuck through the decades, plaguing posters and arming journalists with quick draw comparisons. Though for me, it’s a tagline that only serves to reduce the film’s radical politics to a feature-length parlour trick. To truly celebrate Variety’s layered approach is to explore the underbelly of 1980s Manhattan – punk-powered and restless.

New York City doesn’t just provide Gordon with a colourful backdrop, it becomes – through evocative uses of colour, camera and sound – a central character, as memorable and mysterious as the people it contains. Cut to the real world of the early 1980s, The Big Apple had nothing but character, owing much of it to the fiscal crisis of 1975 that, along with the president’s refusal to help matters, prompted the (less than encouraging) headline, “Ford to City: Drop Dead” in New York Daily News. With the economic engine of the world rattling towards bankruptcy, social services were cut, rents dropped and crime doubled. This led many citizens to believe that the City was beyond redemption, and by 1980 nearly a million people had left.

“It was a ghost town”, Gordon recalls in an interview with Grandlife, arriving in Downtown that same year. The filmmaker, along with a heavy influx of art school dropouts and rural refugees, came to the City of Dreams in the hope of finding cheap digs and a place to play. Lady Liberty did not disappoint. The Lower East Side soon became a hotbed for artistic endeavours, providing a concrete canvas for penniless punks with bold ideas. The No Wave scene, as it became known, proved a rightful heir to the avant-garde legacy that artists like Andy Warhol and Jack Smith helped cement. “Nobody was doing what they were good at,” John Lurie tells Celine Danhier, in her documentary Blank City (2009), “the painters were in bands, the musicians were making films.” It was a cross-pollination of ideas and disciplines that, at its heart, sought to find new forms of expression, irrespective of technique.

For Gordon, this creative mishmash “wasn’t driven by the market or Sundance, but driven by people’s creative inspiration to make art for each other,” and with credits reading like a Pick ‘n’ Mix of underground pioneers, Variety was the shining example. Kathy Acker, Nan Goldin, John Lurie and Tom DiCillo all pitched in; in fact, Variety was producer Christine Vachon’s first gig before she helped kickstart New Queer Cinema a decade later. And thanks to Gordon’s intensive pre-production, it wasn’t just the people who were colliding and combining on set. The director smuggled fact into fiction in order to shape her story. From interviewing sex workers, to porn shop field trips, a unique insight was drawn from the unseen politics governing men, money and Manhattan.

Variety was one of the first films to rise above this underground scene, predating Jim Jamursch’s breakthrough the following year with Stranger Than Paradise. Gordon’s subsequent features, though few and far between, retain her distinctive touch but lack the magic of her debut. What keeps me under its spell isn’t the Hitchcockian approach, but how it preserves the past. Not only a time capsule of a pre-gentrified Downtown, Variety reminds us of a lost freedom of American independent filmmaking: a time before greed became the creed, turning our relationships into contacts and our creative spaces into marketplaces, where content conquers art. In other words, it was a time before they paved paradise and put up a condo block.

Variety was re-released on Blu-Ray via Kino Lorber on September 29