The primacy of the long-form television drama is something so well established now, that it’s almost hard to imagine what we did with the time we currently invest in such series before their inception. As has been noted before, The Sopranos (and to a lesser extent, prior to that, Twin Peaks) were the shows that kickstarted it all. Since then, a number of great series – The Wire, Deadwood, Breaking Bad, Mad Men and Boardwalk Empire, to name but a few – have further contributed to the sense, increasingly shared by audiences, writers, directors and actors alike, that the long story arcs and sense of immersion permitted by the lengthier format offer something deeper, more satisfying and certainly more addictive than the overly restrictive 90-minute movie template.

As anyone who has seen an episode of a network show such as The Blacklist will attest, however, there is clearly a colossal gulf between the worst and the best on offer. I have to confess, after watching the finale of series four of Boardwalk Empire, I did wonder how on earth such intense dramatic heights could be surpassed – then True Detective came along. For those of you who gave up on Boardwalk Empire after the first or second series, I urge you to give it another try. Most large ensemble pieces take some time to establish their sense of narrative and mood and by series three and four it was hitting near Shakespearean levels of dramatic intensity. However, by focusing instead on two leads, compellingly portrayed by Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson, and being born of the singular vision of writer Nic Pizzolatto and expressed with visual flair by director Cary Joji Fukunaga, True Detective manages to attain such aesthetic grandeur in the space of a mere few episodes.

Although at first glance there is much that appears familiar about the show’s set-up (two detectives investigate a ritualistic murder with possible occult connotations out in the Louisiana sticks), there is also much that is unique. Employing the agency of a single director and a single writer clearly goes against the grain of the more collaborative approach usually common to televisual drama. It is this unified intent that allows the show to be both more stylistically ‘out there’ and thematically coherent than any show that has preceded it. Whilst I’m fully aware that positioning myself against the critical consensus that Breaking Bad was a masterpiece may not do me any favours, I have to say that the reason I found myself immune to its charms was the fact that I found it to be too much an assemblage of parts that refused to adhere to any stylistic whole. Certain elements I found to be utterly compelling, while other parts seemed dreary in comparison, or worse still, unbelievable or totally out of place in its ongoing narrative. This is not the case with True Detective. Each and every element – visually, thematically and musically – fits perfectly together into an unsettling, beautiful and singular vision.

This unique quality is clear from the moment the opening credits roll. A refinery positioned at the edge of a wasteland of scrub grass is glimpsed through a haze of industrial smoke as the languidly strummed guitar and initially torpid vocal of the theme tune (The Handsome Family’s ‘Far From Any Road’, picked by musical director T Bone Burnett) builds slowly to a crescendo over images that use human elements to frame the environmental backdrop of their Louisiana setting. The lower half of main character Detective Martin Hart’s head, with the top replaced by industrial cooling towers, a single female mascara’d eye reflecting a lamp-illumined row of trucks minus their trailers, the curve of a woman’s naked back containing a desolate, abandoned child’s play park, Hart’s foil Detective Rustin Cohle’s face licked by orange flames, and then the images running by a second time, as if in anticipation of the philosophical theory of ‘eternal recurrence’ later elaborated in the series. The series’ use of music is exemplary throughout, and a number of episodes conclude with great tracks from the likes of the 13th Floor Elevators, The Black Angels and Grinderman.

Another way the show distinguishes itself from others is in the knowledge, established clearly from the outset, that this story will run for a self-contained eight episodes and after that, should a second series be commissioned, will continue with a different story and a different cast. No doubt this appealed to McConaughey and Harrelson, both of whom are established Hollywood big players, but it should also come as a refreshing change to those of us who have seen promising shows slowly descend into mediocrity over time. For anyone who is familiar with McConaughey only from his appearances in lacklustre romantic comedies, his enthralling performance as the nihilistic, emotionally damaged yet dangerous Detective Cohle will come as something of a shock. For those who caught his performances in the excellent Killer Joe (2011) and Mud (2012), however, the transformation will come as less of a surprise. Woody Harrelson, who originally read for the part of Cohle, is excellent too as his straighter, although by no means straight-laced, partner Marty Hart. On screen together the pair, apparently good friends in real life, radiate an incredible chemistry, complementary opposites to each other’s characters, whose traits develop in ways that confound and transcend their pulp genre types as the series progresses.

Pizzolato’s unusual use of narrative structure also marks the series as unique and gives it a freshness that compels repeat viewings – almost as soon as the end credits start rolling. A friend of mine texted me after an episode, saying: "That was so good that I put it back to the start again the moment it ended." Although I’ve watched other favourite shows more than once, this kind of short term itch to re-watch episodes before the full story arc has settled is an entirely new experience.

Episode one opens with what looks like two characters, faces and forms almost entirely eclipsed by darkness, carrying a suspiciously wrapped bundle into a field. We see momentarily a section of land aflame from the distance, then the camera lens as the record button is pushed in the interview room, seventeen years later, as Hart and Cohle are questioned separately about the incidents that transpired during their hunt for the killer. Not simply content with a narrative device that allows for events to unfold in two separate time lines before possibly converging in the present, Pizzolato also uses non-linearity to great effect within those time lines themselves, providing a cut-up to the flow of events that further inspires the audience’s attention to the narrative’s unfolding clues. Following the early disclosure of Cohle’s nickname, The Taxman (due to his carrying a big ledger for note taking), by Hart, Cohle in his own interview says, tellingly: "Yeah, of course, I’ve always taken a lot of notes. You never know what the thing’s gonna be do you? The little detail, somewhere down the line that makes you say ‘aaah’ that breaks the case". It’s impossible not to perceive those remarks as being, in some sense, aimed directly at the viewer.

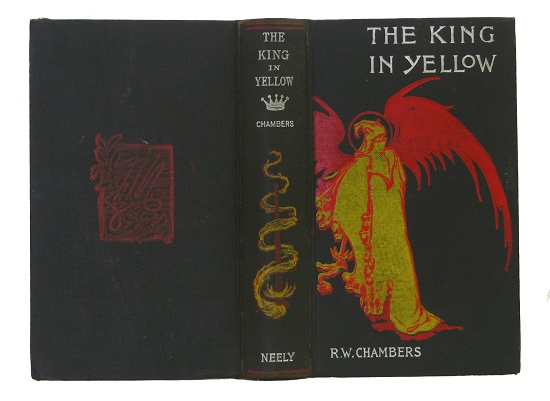

Yet another way in which the series diverges from its pulp genre origins lies in the philosophical and literary references Pizzolato adds to his Southern Gothic noir narrative. Although the name itself, True Detective, brings to mind those magazines with lurid covers that purport to retell true crime stories framed with all the trappings of the hard-boiled detective genre (and perhaps also nods in the direction of future self-contained stories), there are also many references to be found to a different genre, also at one time to be found in similarly sensationalist types of magazines, namely the kind of weird fiction and cosmic horror typified by the work of H.P. Lovecraft. Robert W. Chambers’ The King In Yellow, a strong influence on Lovecraft, is the source of many of the cult references in the show. The stories in the book centre around the fictional titular play, which sends its readers into a state of insanity. It also alludes to a mysterious city called Carcosa, the name of which Chambers himself took from the Ambrose Bierce story ‘An Inhabitant of Carcosa’. The philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, Romanian thinker E. M. Cioran and modern horror writer and "pessimistic philosopher" Thomas Ligotti, form the basis for Cohle’s dark and nihilistic world view. Specifically, Nietzsche’s notion of eternal recurrence, the concept that the universe will recur again and again ad infinitum without hope or possibility of change, is discussed by Cohle in episode five. Similarly, Cohle’s stated belief that, "We became too self-aware; nature created an aspect of nature separate from itself. We are creatures that should not exist by natural law," is a direct echo of a sentiment expressed by Ligotti in his philosophical work The Conspiracy Against The Human Race. As with all truly great works of fiction, this intertextuality is there for those with a will to discern it, and is in no way an essential prerequisite for enjoyment of the show.

Although the series has received almost universal critical acclaim, as well as eliciting an unprecedented level of internet commentary and speculation, some writers (such as Emily Nussbaum of The New Yorker), have criticised it for being too masculine and stereotypical in its presentation of female characters as "the victim, harlot or nagging wife." As Michael Noble points out on denofgeek.com, although such criticisms are in themselves fairly accurate and certainly true to the type of genre from which the show is derived, they are in a sense misplaced. True Detective clearly critiques a male world view at the same time as it presents it. Much of the ‘evil’ depicted in the show, from Marty’s ongoing family difficulties, which he categorises as arising from his ignoring the answers to all his problems which were under his nose all along, to the ritual murder of Dora Lange herself, stem directly from ignoring the female perspective. Nussbaum’s description of the character of Rustin Cohle as "a macho fantasy straight out of Carlos Castaneda", only partly captures his complexity. As the show progresses, we come to learn that Cohle isn’t simply the nihilist he at first appears, and that he exhibits such opinions precisely because at one time, he felt and lost too much.

Although Nussbaum no doubt conjures up the name of Castaneda (who wrote a series of enormously popular ‘novelistic’ books purporting to tell of his experiences with a mystic Yaqui Indian shaman called Don Juan Matus from the late 60s onwards), to refute his philosophical viewpoint as charlatanic in nature, he more properly fits Don Juan’s definition of "the warrior’s way". The (most likely) fictional Don Juan tells Castaneda that the warrior derives his power from the fact that he has faced his death and therefore has nothing left to fear. Thus it is with Rustin Cohle, who has already experienced the very worst things that life can throw at him, and therein lies both his strength and his weakness. When Marty voices concern for his partner going undercover later in the series and Cohle replies that the worst that could happen "is a bullet in the head", he makes it very plain that there are far worse things that can happen. In moments such as these, Cohle invites both awe and pity, and it is these two aspects which make him such a compelling character. I wouldn’t describe myself as a nihilist, but it can be hard to deny that every dark sentiment that Cohle utters rings true at some deep, dark level.

As he says to Marty in episode one: "People out here don’t even know the outside world exists… might as well be living on the fucking moon."

Marty replies, "There’s all kinds of ghettos in the world, Rust", only to be told, with chilling finality: "It’s all one ghetto, man. A giant gutter in outer space."

True Detective is currently showing on Sky Atlantic in the UK