The abiding image of the silent movie accompanist is that of the lone pianist improvising on the spot to a flickering projection. This is the picture which we’ve encountered time and again, whether it be on the cinema screen, in documentary recreations or perhaps even in real life. And yet it’s also one that is slowly slipping away. The art form remains – Neil Brand and John Sweeney being among those who continue to play at silent film festivals and Southbank screenings in such a fashion – but the parameters are widening. Think of any major silent-era presentations from the past couple of decades and it’s more than likely that they’ll be high profile affairs involving contemporary performers. In 1993, for example, the National Film Theatre played host to Nick Cave, who had teamed with Dirty Three for the occasion, as he accompanied Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent masterpiece The Passion of Joan of Arc. In 2004, at a free concert in Trafalgar Square, the Pet Shop Boys unveiled their brand new score for Battleship Potemkin with the aid of a full symphony orchestra. Last year Air did much the same at the Cannes Film Festival, although the film this time around was George Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon.

The Air soundtrack is an interesting case insofar as their score became as much a news event as the silent classic it accompanied. The Méliès film was a big deal, having recently undergone an 11-year restoration process which, frame-by-frame, had preserved an original hand-painted print. A Trip to the Moon hadn’t looked this lovely in over a century, and yet you could be forgiven for thinking it a mere afterthought. In some quarters the press coverage was heavily centred on Air, while those of us here in the UK wishing to own the film on DVD without going down the import route had just a single option: to buy the attendant LP where it appeared on a bonus disc, a move which only seemed to reinforce its relative standing. (A standalone release did eventually emerge, but that was a mere fortnight ago; the Air album has been available since February.)

Air came to A Trip to the Moon having previously scored an entire feature – Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides – in 1999. Such a transition has become increasingly common over the years with a number of well-known composers making the switch. Michael Nyman, after numerous Peter Greenaway collaborations and that very famous score for The Piano, approached Dziga Vertov’s experimental tour de force Man with a Movie Camera in 2002. Simon Fisher Turner took a longer route, starting out in Derek Jarman features before slowly transitioning into Jean Genet’s Un Chant d’amour (a film which, despite being made in 1950, was shot silent and never had an official soundtrack) and the recent, highly prestigious gig of scoring The Great White Silence, a major restoration project for the British Film Institute’s National Archive.

Speaking of the BFI, they’ve been instructive in commissioning so many of these pairings, whether it be Nitin Sawhney on the recent re-release of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger (Sawhney having previously scored a number of television documentaries as well as Mira Nair’s The Namesake) or James Bernard – the man responsible for all of the truly great Hammer horrors with their soundtracks – bringing his distinctive touch to one of the absolute classics of the genre, FW Murnau’s Nosferatu. Furthermore, the BFI’s DVD label has often supplemented these high-profile affairs with their own comparatively low-key, but arguably all the more leftfield offerings.

In truth the more unlikely collaborations make up just a portion of the BFI’s silent movie output on disc. As well as releasing the majority of the projects already mentioned (the Nyman, the two Fisher Turners, the Bernard), they have also served up a number of conventional affairs. Indeed, when it came to issuing the complete surviving works of British early cinema pioneer RW Paul, the lone pianist (embodied in this case by Stephen Horne) made for the perfect choice. Similarly, the big names have a tendency to put in regular appearances: Neil Brand accompanying Charles Dickens adaptations or the experimental colour films of Claude Friese-Greene; Carl Davis playing along to Chaplin. Sheffield outfit In the Nursery have also arguably entered the mainstream after finding themselves in charge of Electric Edwardians, a touring programme and subsequent DVD devoted to the turn-of-the-century actualities of Mitchell & Kenyon, one of the major film finds of recent memory.

The more surprising commissions have run in parallel to these releases and tended to catch the viewer completely unawares. While the pairing of Davis with Chaplin, say, is hardly going to raise any eyebrows, the same cannot be said for some of the more recent DVDs. When the BFI brought Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali’s L’Age d’or and Un Chien Andalou to Blu-ray last year, the latter was accompanied by an exclusive Mordant Music soundtrack. Buñuel had originally intended his surrealist short to be screened alongside a pair of tangos and excerpts from Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. Now it came with sampled animal noises and moments of sheer intensity; the visual assault on the senses finding its aural match. Just as confrontational were The Erotic Films of Peter de Rome. Their maker had previously screened them to friends while playing Miles Davis or James Brown records, but for this release the BFI opted for the talents of Cyclobe’s Stephen Thrower and Zombi’s Steve Moore, in doing so finding unexpected bedfellows. Sometimes the BFI discs have surprised simply because such instances crop up in strange places. Saint Etienne, for example, can be found nestled in a compilation of documentaries from the Central Office of Information. Magazine’s Dave Formula, meanwhile, was brought in to score a number of silent sex education shorts.

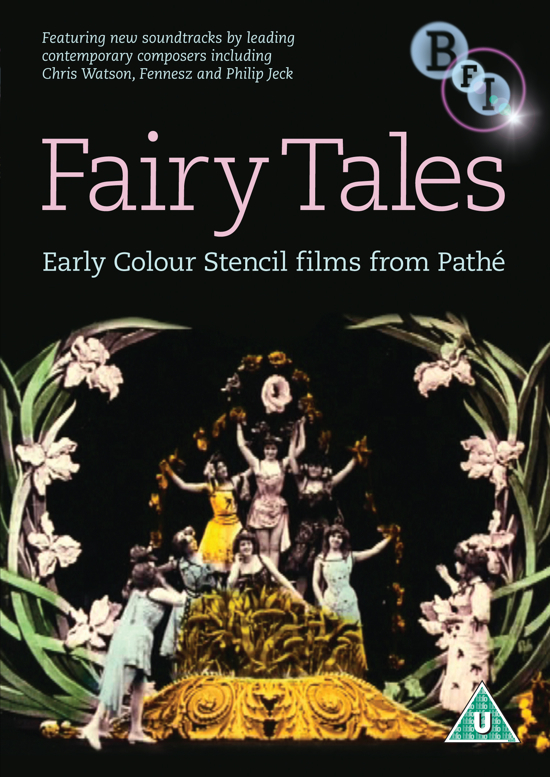

The latest offering from the BFI is certainly among the most idiosyncratic yet. Entitled Fairy Tales: Early Colour Stencil Films from Pathé, this new DVD takes 25 short films from the early 1900s and pairs each of them with one of the recording artists on Touch Records’ impressive roster. Thus Chris Watson accompanies Métamorphose du papillon (Metamorphosis of a Butterfly), a two-minute piece of dance and primitive special effects. We also find Philip Jeck performing live to a 1907 adaptation of the Cinderella story; Christian Fennesz scoring La Peine du talion (Tit for Tat), a cautionary tale involving vengeful butterflies; Marcus Davidson taking on a brief record of the once-famous ballroom dancers Boldoni and Solinski, and so forth.

As Touch’s Mike Harding makes clear in his liner notes, some of these choices were natural fits. Davidson, to name just one, works in ballet so it was easy to allocate him two of the dance-based shorts. Yet such options can only last so long meaning that, across the 25 titles, some less serendipitous pairings had to take place. Furthermore, the scope of both the films themselves (though all, to a greater or lesser extent, contain fantastical elements as the Fairy Tales moniker no doubt suggests) and the various musicians and composers results in an incredible sense of variety. The performers differ wildly in terms of their training, their backgrounds, their nationality, their influences, and so on, and with that comes a much more apparent sense of surprise. After all, when you commission a single artist to compose a new soundtrack you know roughly how the end results will sound based on their previous works. But when you commission an entire record label you’re opening up these films to a much broader spectrum of possibilities.

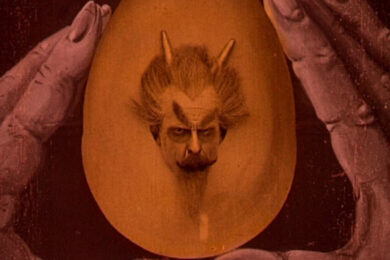

The BFI’s sole remit before handing the films over to Touch was simply that the integrity of the original works be respected. Other than that the various composers could create their own rules. Part of the pleasure in viewing Fairy Tales comes from discerning the quirks and influences at play, in detecting those elements which seemingly gave birth to the soundscapes on offer. Few of the artists foreground melody – only experimental pianist Sarah Nicholls seems to favour this route – instead opting for less immediate solutions. The primal noises throughout Leif Elggren’s offering, Ali Baba et les quarante voleurs (Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves), would appear to recall those of a cave opening to the command of ‘open sesame’. One of Harding’s own contribution, for Le Spectre rouge (The Red Spectre) and in partnership with Michael Esposito, makes use of period projectors to create a kind of mock-diegetic environment. Jana Winderen went as far as to record her soundtrack for Un Drame au fond de la mer (Drama at the Bottom of the Sea) underwater.

The Winderen piece is as good an example as any as to how these compositions can really make their stamp on the material. Though barely a minute in length, it manages to create the kind of mood in which we are drawn to the more uncanny elements such as the corpse in the corner of the screen. This effect is repeated time and again throughout Fairy Tales in terms of making aspects of early filmmaking techniques which once seemed so quaint – all those dancing girls, disappearing acts and rudimentary make-up effects – now appear decidedly strange. When placed in the hands of a pair such as Joachim Nordwall and Henrik Rylander we are given the soundtrack to an ever-worsening nightmare or a ritual akin to Kenneth Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother (which famously came with an improvised synth soundtrack courtesy of Mick Jagger) and that can be a fascinating experience. Of course, such elements have to exist in the original films in order for us to detect them, but oftentimes it is as though they’ve lain dormant for more than a century.

Had these Fairy Tales come with the lone pianist as their accompanist would we be saying the same thing? And how will casual buyers and silent movie purists react to having been lured in by the safe title and understandable expectations for the quaint? Some of these soundtracks infuriate rather than fascinate, but that is surely an unavoidable side effect of mounting such a project in this manner – and I strongly suspect that the infuriate/fascinate split is entirely subjective. Importantly, this new release has us asking these questions and looking at these films in a different light. Of course, the naysayers can always turn down the volume, but in doing so they’re also turning down the challenge.

Fairy Tales: Early Colour Stencil Films From Pathé is out now on DVD via the BFI.