In the classic counter-culture novel Illuminatus!, Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea speculate on the JFK assassination. Let’s assume, they say, that the conspiracy theorists are right. Not just one, or a combination of a few, but all of them. You’d be forced to conclude that, had you been at Dealey Plaza on November 22nd 1963, you couldn’t have moved for all the Mafia hoods, CIA operatives, KGB spies, Cuban Revolutionaries, Freemasons, Cabbalists, Bavarian Illuminati and aliens from Sirius training their gun sights on the president’s motorcade.

The JFK conspiracy is now so multi-faceted and complex, it’s become a kind of meta-conspiracy, a Conspiracy Theory of Everything. It’s also the blueprint of what Richard Hofstadter, in an essay for Harpers magazine published a year after the assassination, called ‘the paranoid style’, in which he reveals a Byzantine wealth of conspiracies in American culture stretching back centuries.

What does any of this have to do with The Saragossa Manuscript? Only that Wojciech Has’s film is a prime example of this paranoid style at work. Certainly its hero, Alphonse van Worden, has good reason to think everyone’s out to get him. As the character Velásquez puts it midway through the film, “Someone must be after you to put you through all these misfortunes.” Someone or something, since for Worden and for us, events unfold along the lines of a Gothic nightmare, with a full compliment of dark omens, including animal skeletons, human skulls, black crows, writhing serpents, alluring succubae and the fog-eyed ghosts of men hanging from the gallows.

The Saragossa Manuscript was released in Poland in 1964 – the same year as Hofstadter’s essay was published, and despite being on the eastern divide of the Iron Curtain, it’s clearly a film of the Sixties. It’s as a psychedelic film that its generally regarded, although this is as much to do with those who championed it in the West as anything else, in particular the The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, who watched it at the Cento Cedar in San Francisco in 1966. The film became part of the Midnight Movie circuit, along with such exotic delights as Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo, George Romero’s Night Of The Living Dead and the pre-Hays Code favourites, Freaks and Reefer Madness. Garcia must’ve experienced an epiphany or two sat at the Cento Cedar, since he took it upon himself to seek out the full three-hour version of the film, a quest completed after his death by Martin Scorsese, whose Masterpieces of Polish Cinema series comes to the BFI next month, and includes The Saragossa Manuscript among its number.

Whether or not any laced sugar cubes ever found their way into Has’s tea I don’t know, but there’s no doubting the qualities those imbibing the cool-aid would have admired. The film is brimming with Bacchanalian revelry, arcane mystery and mortal dread. It has an elliptical, repetitive and disjointed structure that is both disorientating and uncanny, Worden frequently finding himself back where he started despite all the frenetic horseback riding, like a character in an MC Escher drawing. Basic leitmotifs like the skull, the gallows, and the giant illustrated manuscript from which the film takes its name, recur like a primal, hypnotic drumbeat.

With its dissembling, fractalised, stories within stories, it’s just the kind of thing you might expect from a writer like Thomas Pynchon – after all, The Crying Of Lot 49, published in 1966, has it’s fair share of occult symbols, secret societies and even a band called ‘The Paranoids’. Likewise, William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch and its cut-and-paste approach to narrative. But there’s perhaps something of a feedback loop going on here, since the book on which the film is based, The Manuscript Found At Saragossa, written between 1790-1810 by the worldly Polish adventurer Jan Potocki, embodies some of the experimental exuberance of early novelists, employing telescoping framing devices to build up a patchwork of interconnecting stories. His novel also reflects a period of tumult in European history not entirely dissimilar to the renegade atmosphere of the 1960s, including a controversial war, ground-shaking advances in technology, and a sense of profound discontent with the established order.

Along with work by Blake, Poe and Sade, The Manuscript Found At Saragossa was adopted as a founding text by the surrealists, and the director Wojciech Has was in turn influenced by surrealism. Some of the imagery in the film is clearly inspired by artists like Max Ernst and Salvador Dali, as well as 18th century contemporaries of Potocki like Francisco Goya, or going even further back, that surrealist favourite, Hieronymus Bosch. It certainly comes as no surprise that Luis Buñuel admired the film, as did David Lynch.

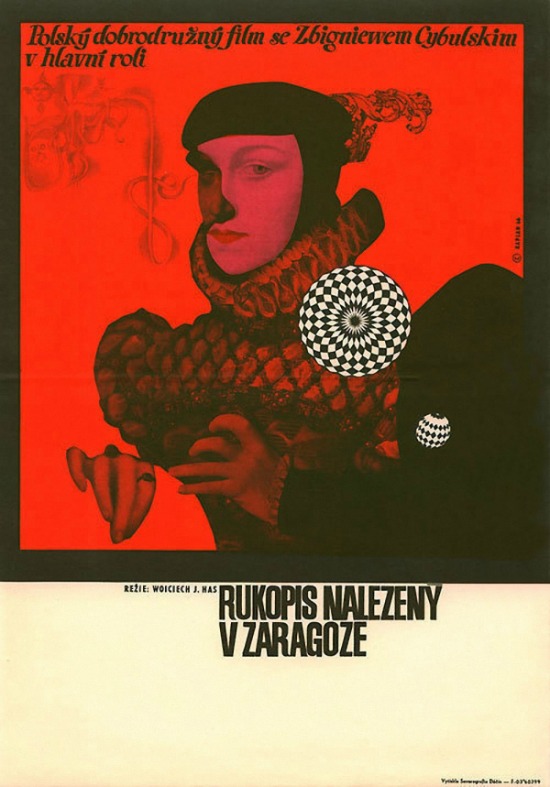

So what is The Saragossa Manuscript about? At a simple level, it’s the story of Alphonse van Worden (played by one of Poland’s biggest stars, Zbigniew Cybulski), a young army officer, who in 1739 is trying to find the shortest route to Madrid from Andalusia in the south of Spain. It sees him moving through the rocky moonscape of the Sierra Morena, a haunted region where, as his servants warn him, “invisible hands push you into the abyss.” Ignoring their remonstrations, he presses on among sinister rock formations and contorted petrified trees, arriving at a deserted inn called the Venta Quemada. It’s here that, to paraphrase Robert Anton Wilson, things turn into something of an astral mindfuck.

There’s no comforting ‘save the cat’ screenwriting formula to fall back on here. This is more a ‘kill the cat and use its skull as a receptacle for LSD-spiked vodka shots’ kind of formula. At the inn, a semi-naked woman directs Worden through a door and along a passageway into a cave decorated with arabesque carvings, and where a feast is laid out, apparently in his honour. Two beautiful women arrive declaring themselves as sisters, and after brief introductions reveal they are also incestuous lovers, but that they’d nevertheless like to marry him (in a two-for-one deal), primarily because he is related to them too. They seduce him and convince him to drink from a chalice made out of a human skull.

He blacks out and wakes under the gallows to find his two servants dead, their skin flaking off. He returns to the inn at Venta Quemada, walks the passageway to the cave, only to find it in a state of antique decay, rats nibbling at human bones. He gets back on his horse and rides to a church, where an old monk greets him, and who, it transpires, is the ward of the psychologically damaged Pasheko. We get a story in flashback about Worden’s father, an obsessive duelist, a story in flashback about Pasheko’s love of his father’s wife’s sister. Then the Holy Inquisition arrives and kidnaps Worden. And so it continues. At this point we’re a little over thirty minutes into a 180-minute film…

In contrast to his Polish contemporaries, whose films were often explicitly social or political, Has was more interested in the terrain of the individual psyche. The Sierra Morena is a world suspended, an interregnum full of potent symbols of ‘the Other’. The recurring images of skulls can be interpreted as so many signifiers incessantly struggling after what cannot be known, namely the existence of non-existence, the void onto which are projected our most primal fears and desires.

It’s nevertheless possible to see Poland’s postwar political plight here, not least in the pervasive sense of disorientation, contradiction and discontinuity, hallmarks of a country manipulated, coerced and occupied by the empires on its borders, and which instilled in Poles the talent not so much for doublethink as triplethink. No doubt the audience at the time of the film’s release would have looked at the Holy Inquisition and seen a wry comment on the secret police, or found in the seduction by the sisters the commonplace briberies and betrayals of a subjected people, or noted in the absurdity of Alfonso’s obsessively dueling father the unquestioning obedience to ideological codes of practice. But the story’s provenance is mythic and folkloric, and the prismatic nature of such stories means they throw light and colour into any historical age or cultural milieu.

After close to three hours down the rabbit hole, the film tries to break the Gordian knot and provide an ultimate ‘reveal.’ In the novel, a prolonged unravelling is possible, but here the effect is hurried and unconvincing. And such an attempt at a conventional dénouement makes little sense in a film where the logic of a fractalised structure is that it remains open-ended. Clearly Wojciech Has and the writer, Tadeusz Kwiatkowski, felt the same way, unable to resist one final mind game with the audience. As the closing titles roll, we’re left in much the same state as the hapless Worden, who at one point concedes that he’s “lost the feeling of where reality ends and fantasy takes over.”

Martin Scorsese Presents Masterpieces Of Polish Cinema begins at the BFI on the 8th of April, with a showing of The Saragossa Manuscript on the 20th. For more information visit the BFI website