Kaneto Shindo’s fifteenth feature The Naked Island is, perhaps, the quintessential humanist film. Centering on a family of four eking out a meager existence on a tiny island in the Seto Inland Sea, the film documents, in exacting detail, the daily trips the husband and wife make to a nearby island for fresh water to tend to their crops and sustain their two young sons. Shindo paints an exacting portrait of their daily life, which, despite the film’s methodical pace, oscillates repeatedly between eliciting a heartwarming and heart wrenching response. Shindo figured among the first wave of post-World War II directors and early works such as Children of Hiroshima reflected the newfound ability to expound an overtly leftist political position within a commercial production framework. However, with The Naked Island Shindo chose to take a much less dogmatic stance, instead fashioning an impressionistic and poetical musing on the state of post-War Japan. This truly entrancing film doesn’t rush through any details, instead slowly building a real sense the struggle to maintain family life on the tiny island.

Less concerned with providing a political critique, The Naked Island allowed Shindo to capture a seemingly pared down story with a grace and clarity, though still with a distinctive edge of experimentation. Indeed, talking of experimentation, it’s perhaps worth singling out three cuts around six minutes into the film for special examination. Within filmmaking, formal innovation works most effectively when it registers as a fresh and exciting aesthetic approach, but also manages to accentuate some element of a film’s central thematic. Therefore, innovation succeeds best when it exists outside the diegesis (style in its own right), but can still underscore a central aspect of the narrative themes. I think that with these three cuts, six minutes into Shindo’s fifteenth feature he creates such a perfect marriage of form and theme.

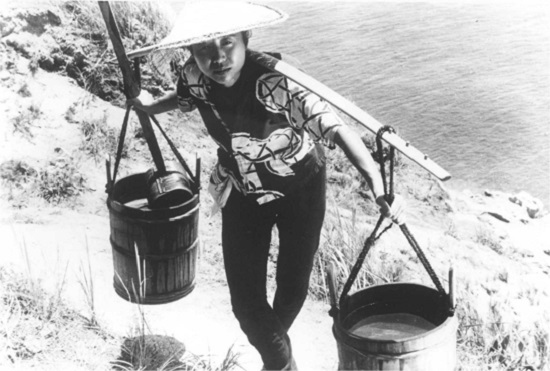

The husband and wife struggle along the waters edge, buckets of water balanced across their backs. The camera is positioned at a fair distance from the pair. Slowly they approach and almost pass out of the left side of the frame. Before they can fully pass a cut shifts the camera further back down the path, retreating from the pair. Again they approach and, before they pass out of shot, again a cut shifts the camera further away. The first instance of this unusual manipulation of cinematic space and time feels rather jarring, though after its repetition for a second and third time we can begin to understand Shindo’s reason for its inclusion. Repetition and retreat are at the heart of Shindo’s formal construction here. Reoccurring episodes of action are consistently framed in a similar manner- accentuating the laboriousness of the pair’s daily routine. Similarly Shindo uses this retreating camera technique to further accentuate the duration of the pair’s multiple struggles, whilst also flagging up the unrelenting topography of the rural locale- shots continually creep up steep slopes away from the pair. There is an increasing realisation that Shindo’s actors truly physically exerted themselves in portraying these characters.

Within this opening half-hour Shindo utilises an almost cranked down Soviet montage style to craft a real sense of the precarity in the family’s working life. This collapses at the half hour mark, when in a devastating moment the wife loses her footing and drops her buckets. It is a testament to Shindo’s construction within the film’s opening that this moment elicits such an affective response from the viewer. The two young sons in the film also offer emotionally wrought performances. Shindo renders them as an almost inseparable unit, darting back and forth across the island; always awaiting their parent’s return, always conscious of their daily struggle to support them. Shindo’s beautiful and exact documentation of this nuclear family makes the tumultuous events of the second half of the film that much more emotionally investing.

In a similar manner to Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Shindo sidesteps an overtly dogmatic political stance to offer a much richer picture of post-War Japan. The Naked Island is a much welcome rerelease, reminding us that a clarity and simplicity of construction can warrant a much increased emotional investment from us as viewers. Eureaka’s Blu-ray transfer is impeccable as always- sharp and crystal clear, yet never blown out. If you want to witness something truly powerful, seek retreat in Shindo’s enriching familial love poem. You’ll care more about these characters than any others on the big screen this year, I guarantee it.

The Naked Island is out now on DVD and Blu-ray from Eureka.