Thursday was supposed to be the glamorous opening night of the Rome Film Festival, where the big news would be the world’s first ever showing of the 23-minute long Tron: Legacy trailer and screening of Last Night, as well as Keira Knightley and Eva Mendes tottering pleasantly down the red carpet. Instead, the big news of the day will turn out to be the occupation of said crimson strip by a thousand-strong group of protesters, led by grass roots organisation Tutti a Casa, who made their feelings known about vicious cuts to public sector funding by the government – just as our heroines were due to make their grand entrances.

It was coming up to 7pm and I was rushing out of the Tron screening room in order to catch a glimpse of whatever dress had attached itself to our English Rose, and fumbling with a camera, notepad and bag while trying to hand back a pair of cheap 3D glasses almost sent me tumbling like a cartoon into a group of middle-aged, upper-middle class ladies. They looked like they had been put through a cement mixer in order to fix their hair and rictus grins, and only their eyes glistening revealed that they were well aware of just how close they were to being squashed by a rotund, uncoordinated Englishmen. Meanwhile the world’s entertainment press, who had gathered for an easy day’s celeb snapping, were instead faced with the site of Italy’s great unwashed ruining their cosy day’s work. No shimmering dresses or glamour; what we had here was a social problem invading our sheltered world.

After I scrambled out of the scrum, trying to find my way through the numerous exits reserved for the press which were now blocked by the burly Carabinieri officers, I retreated to the press room to sit down and start scribbling. Soon after, my Spidey senses tingled, and sure enough a stampede for the main stage area of the Auditorium nearly blew me off my chair: Mendes and Knightly had both made their approaches through the knot of protesters. I managed to get out there just as the speeches were finishing, and saw the two stars walking away from the exact spot at which I had been standing not 15 minutes previously – close enough to have felt either one of them fart. Meanwhile, the security were more or less pushing back angry snappers who were desperate for a shot at the stars of the show, flashbulbs were going off in a rapid staccato rhythm and once it became clear there were no more photos to be had the blind rage filtered out into a stifled frustration; all except for one English snapper who nearly burst my eardrum with a loud ‘FUCK!’ which followed him down the concourse as he charged past me, desperately hoping to flank the security. No dice, however – they were gone, and all we were left with was the grim reality of workers being robbed of their livelihoods, and their battle to save them.

Times are tough in Italy: the government nearly fell in the summer when President of the Camera (kind of like being Speaker of the House in the House of Commons, but less neutral) and ex-Fascist Gianfranco Fini decided that he had had enough of Silvio Berlusconi’s mode of government (too many examples to list – seriously), and split with his right-wing Popolo Della Libertà party to form his own faction. However, despite this late discovery of a conscience which left Uncle Silvio without a majority in the Camera, he’s still in power and still up to his old tricks. Mostly because Fini tends to vote with the government on important matters, one of which is the allocation of public funds, or lack thereof: Berlusconi has proposed huge cuts to everything from health to the police, and yes, the arts, hence why this little barny came crashing into our comfy lives. According to Sandro Bondi, the current minister for culture, the protest “demonstrates the level of… intolerance from the part of people who agitate in the name of culture but who have nothing to do with it”. But then she would, given that there’s no way anyone in the Camera is going hungry; they have the highest salaries and most perks of any politicians in the whole of Europe, and many (most?) of them are nest-feathering crooks on the take, corrupt either financially or politically. Or both.

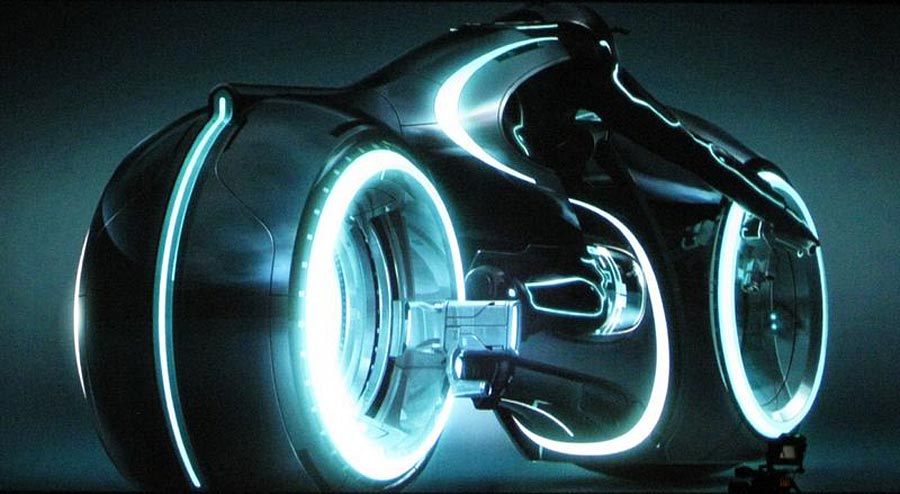

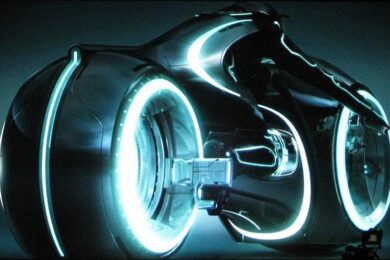

So yes, the films. I must admit that I’ve never understood the appeal of Tron; it always seemed to appeal because of its technical accomplishments rather than what it stood for as a piece of art. It’s a very cold film. What we were treated to was five scenes from the film, in chronological order, which broadly mapped out the plot to us and introduced the main characters. We started out with Sam Flynn (Garrett Hedlund), son of the first film’s hero Kevin (Jeff Bridges), being dropped in on by his dad’s old friend Alan Bradley (Bruce Boxleitner) and encouraged to investigate a pager message sent to him by a long since dead phone number. His snooping rather obviously leads him to being zapped into The Grid, whereupon he has to do battle in ‘the games’ until he is rescued by Quorra, an improbably sexy program who we’d bet good money does something rude with our hero Sam, and who takes him to meet his father. After their strained, wooden reunion we’re treated to a series of quick edit sequences that show Jeff back in the saddle presumably fighting to get off the grid and back home. Frankly, if you’re losing your patience before the end of a 23-minute version of a film like I was, then it’s probably for the best that you found that out before sitting down for the full length version.

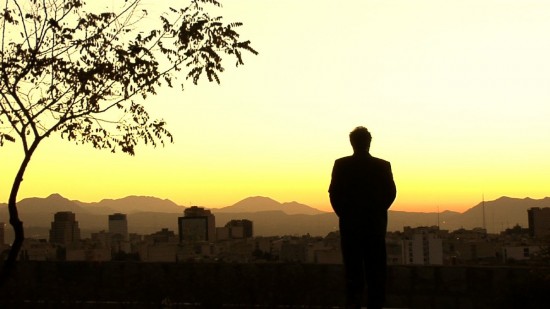

Much better, however, was Dog Sweat, a film set in Tehran and produced with American and Iranian talent. It centres on the mostly interconnecting lives of several young Iranians, all striving to push against cultural and religious norms as the spectre of an oppressive state hangs heavy over them. Each story arc is set up early on: we have a group of young lads who are always on the lookout for American booze; a gay man who is under constant pressure to marry by his mother (who is well aware of his long-term ‘friendship’ with another man); a young woman who has ambitions of being a singer but has to clandestinely record her songs in case the police come knocking; the feminist daughter of a ‘liberal’ family who is having an affair with an older married man, and her friend who spends the whole film being the light relief as she searches for a place to lose her virginity with her new boyfriend. Have you got all that?

Somehow director Hossein Keshavarz manages to satisfactorily tie up these threads within 90 minutes, without once drawing any 2D characters, and eliciting uniformly excellent performances from his cast. He has also managed to make his film explicitly anti-government without ever bringing officialdom into the story (they cast a heavy pall over the film, however, despite their absence), and it is even anti-religion without ever denigrating the spiritual beliefs of his countrymen. He never makes the agents of the characters’ repression anything less than human – especially when they’re oppressing themselves.

One of the main themes of Dog Sweat is the comfort that can be had by giving in to cultural pressure, to stop fighting the system and to live your life away from the fear that being different brings. The mother of Mahsa, the wannabe singer, pleads with her to drop her dreams and marry a nice man, as it’s “the only way to happiness”, and in one of the key scenes of the film, when her story and another major character’s intersect, she is told “you always have to fight who you want to be… sometimes it’s just easier to give in.” This way, they’re away from prying eyes. Hopefully, prying eyes will be all over Iran on Dog Sweat’s release.

The press conference with Keshavarz and his producer Maryam Azadi was sparsely populated, mostly with Italian hacks, each of whom was intent on bringing their political agenda to the occasion, rather than ask questions about the film itself. It seemed to me that they were more interested in getting a juicy anti-government quote out of them – to paint them as a pair of pro-democracy revolutionaries – rather than simply as young film makers of considerable talent. The fact of the matter is – and I discovered this over the weekend, when I went to talk to them in a more relaxed setting near the Spanish Steps – that it’s simply too dangerous to make public declarations of rebellion against the government; not just for them, but for the actors, of who we were warned pre-conference wouldn’t have their identities revealed. Keshavarz doesn’t have the political power or financial backing of someone like Benazir Bhutto, for example (of whom more in part two of this blog). They don’t even have a distributor backing them, so you can see why they’re so cautious in what they say about their homeland.

However, that didn’t stop the locals persisting with that line of questioning, with one hack asking whether Iran is “ready for change”, a question so banal it could have come from the mouth of jugged-ear establishment buffoon Andrew Marr. It got the response it deserved: “What does that even mean?” They also emphasised how often social rules are bent, or even flat out ignored, something that you see well represented in Dog Sweat. “It was something we wanted to put in the film: that they [conservative social standards] don’t make people think, ‘I can’t do this, and I can’t do that’,” said Keshavarz. “For them it’s just the landscape to their lives, and they’re gonna live their lives the way they want to, regardless of the details.”

The Iran we see in Dog Sweat is young (two-thirds of Iran’s population are under 30-years-old, we were told), middle class and overwhelmingly urban: between 80-90 per cent of Iran’s population are based in cities, and Tehran has 20 million inhabitants. It’s a vibrant, young place, far from the stifled, closed country that we in the West are used to seeing, and even further from the Iran that the country’s film industry ever talks about (“Iranian films are usually about villagers and mountains and faraway places or very small young children”, said Keshavarz). As such, they had to shoot the film in a covert fashion in order to avoid the wrath of the censors and the authorities; when your president tells you that gay people don’t exist in Iran, you are taking a big risk in shooting a scene in a public park in which one of your main characters has a row with his former homosexual lover and then cruises for sex after being rebuffed by him. It’s not hard to see why they hid cameras in bushes in order to not attract attention to themselves. The same goes for the actors too; the final scene of the film, the closing of the warmest story arc in which a young unmarried couple search for a place to ‘be alone’, had to be changed when the father of the girl involved found out about her role in the film and barred her from doing any more work on it, giving them three hours to come up with and film an entirely new ending. What they came up with I can only imagine will be a slap in the face to her father’s disciplinary action should he ever see it, but given that the film won’t be distributed in Iran at any time in the near future, there’s not much chance of that.

Dog Sweat takes many of its cues from the great teen films of 1950s and 60s Hollywood. It shows an Iran in which the youth of the country are slowing picking away at the fabric of conservative society, which is curious about the west and hungry for freedom and liberty, however corny that may seem. But more than that, the makers show considerable skill in satisfactorily winding up six separate stories in the space of only 90 minutes, with their barely a scene that isn’t dripping with pathos and black humour. It’s a timely, necessary film, which shows us a side of Iranian culture we in the west never see. And yes, one that is ready for change.

The International Film Festival Blog Part Two

There’s never any space in the press room, so most of my time that’s not spent in press screenings and press conferences I spend typing away in the public canteen. All of its outer walls are glass, and it offers a perfect view of the Auditorium Cavea, an open air venue which in the summer hosts gigs. Up until Friday evening it was where the Film Festival red carpet parade finished, and the site of the occupation spoken about in the previous article. As I typed this however it was the snappers who were coaxing Italian celebs to pose for them, while a sparse group of locals lined the barrier looking for autographs. For the rest of my time there wasn’t any more excitement, or at least no more civil disobedience. Tutti A Casa set up shop in an office alongside the red carpet, and every now and again one of their flyers would be thrust into my hand as I charged from the tram stop to one of the screening rooms, but other than that we heard no more from them. No more stories would be falling into my lap; from now on I’d have to look for them.

Last Sunday I met up with Hossein Kesharvaz, the director of Dog Sweat, and his producer Maryam Azadi, at the base of the Spanish Steps. We’d arranged to meet up for lunch at one of the few places worth eating in round there, but it was closed, so we wandered around, making small talk, before settling on a place that was making a killing charging tourists too much for shit food. However, given that I’d been leading them around like a novice tour guide for a good 20 minutes, I decided it would probably be a good idea to sit down and ask some incisive questions. While waiting for the crappy Amatriciana to arrive we chatted about the Iran that they know, or at least knew: "we’re not going to be able to go back to Iran right off the bat", explained Kesharvaz.

"In Iran it’s kind of like in the US in that I don’t know anyone who voted for George Bush, but then half the country did, and I don’t know anyone who voted for Ahmidinijahd either." Unfortunately most of the conversation was punctured with "this is off the record", so the most revealing stuff will have to stay on my laptop. But suffice to say the current leader’s opinion of the West and the United States isn’t universally shared in the country, nor are they having it all their own way.

One of the aims of Dog Sweat was to show how similar Iranian youth are to the ones glowering at us on street corners, and to do that they took their cues from films like Splendor In The Grass and Tokyo Story. The influence of both can be seen all over the story of Mahsa, the wannabe singer who is under pressure from her mother to marry a nice boy and settle down, but who is genuinely fearful for where her rebellious streak will take her: "This is the only way to happiness", she explains. It’s notable that none of the parents, despite knowing of their offspring’s illegal activities, ever hints at going to the authorities. All they want is for them to give in like they did, and escape the potential wrath of the moral police: "Because we were making this film underground there were so many things we wanted to talk about," says Kesharvaz.

"We wanted it to be a portrait of a generation, you know? What it feels like to live in Iran. We also didn’t want to make it like Crash, where everything connects. That was too cheesy. So the stories are emotionally tied, but one of the things we realised from the beginning was that one of the things unifying the film was young people who are all challenged by society to live a certain way, and they either succumb to it or not.

"You know, living in a ‘closed society’ that doesn’t have the same freedoms as other places, it’s not like there’s anyone beating you over the head with it; it’s lots of little things, and I think the biggest things that limit your actions are well-intentioned: often the pressure comes from your own family. I like how in Tokyo Story you really feel bad for the parents, the kids oppress the parents. The thing is for Mahsa’s mother is that the girl is her life – all they want is for the girl to get married, but once they do they’re all alone."

Dog Sweat makes a political point without ever explicitly evoking politics, and as such marks it out from many of the other films at the festival that are trying to say something. One such film was Bhutto.

It’s been nearly three years since Benazir Bhutto was killed in a suicide bomber attack while on her way from a Pakistan Peoples Party rally in Rawalpindi. The Pakistan general elections were due to take place in a few week’s time, and Bhutto was the key opposition candidate, having only three months before returned to Pakistan from self-imposed exile in Dubai. In fact it was widely assumed that she would win the elections, had she not been killed, and widely speculated after her death that General Pervez Musharraf was responsible, if not for ordering her assassination, then for deliberately providing lax enough security such that if someone was to attack, there would be little she or her entourage could do about it. It’s not as there hadn’t been warnings: there had been another attempt on her life – another suicide bomber – on 18 October 2007, while she was en route to a rally in Karachi, so it’s no surprise her supporters smelled a conspiracy. Bhutto, the documentary of her life, makes it quite plain that after a lifetime fighting the political establishment and military, they finally had her bumped off. They even show video footage of her being shot before the explosions. It’s a shame then, that it’s not as thorough with the rest of her life.

Let’s get this straight at the outset: Bhutto is not a dispassionate recount of Benazir’s life. It’s quite clearly enamoured of its eponymous hero, and presents her in the sort of soft-focus, adoring light that Princess Diana still receives in the Daily Express. But it does have some fantastic material, including $250,000 worth of archival footage, interviews with many of the key players (including Musharraf) and narration from the woman herself – director Duane Boughman told us in the press conference that followed the screening that they found tapes of her speaking about her own life that no-one even knew existed, and went to great expense of cleaning them up – and even if the lack of rigour directed towards Benazir lets the film down, it excels in telling the story of Pakistan. As Boughman says, ‘you can’t tell the story of Pakistan without telling the story of the Bhuttos. The documentary is at its strongest when focussing on the events that surround the family, rather than the family itself. It explores the Partition of (and Pakistan’s subsequent battle with) India, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the execution of her father and the various ways in which Western nations helped foster Islamic fundamentalism, while using Benazir as a central figure through which we see these events unfold.

The problem with the film is that producer Mark Seigel was a good friend of the Bhuttos, and described Benazir to us as "the most remarkable woman" he ever met in his life, and "certainly the bravest" (with "movie star looks", no less); anything with him involved is bound to be less than impartial. Very little is made of her alleged involvement in her husband’s alleged corruption, for instance, nor the gunning down of her brother Murtaza by the police, which happened just outside his home.

The latter is given particularly appalling treatment, with Murtaza’s daughter Fatima standing at the scene, raging at the camera, blaming her auntie followed by images of Benazir crying with grief. She couldn’t have been involved, we’re told. Maybe not, but her husband Zardari could have been, and the clearly orchestrated death of a political dissident takes more explaining away that what we’re given.

Even less subtle was We Want Sex [released in the UK as Made In Dagenham], a charming comedy about the 1968 industrial action by women workers at Ford Dagenham which eventually led to the Equal Pay Act. Director Nigel Cole made it clear in the literature we were handed at the press desk and in the subsequent press conference that his aim was to make a bright, populist film about the necessity of strike action that "won’t just get played at a few cinemas in the major cities", and judging by the wild applause it received at the closing credits he’s done it. This is Italy, mind you, where sentimental nostalgia always goes down a treat.

The film focuses on the lives of three women, with Rita, a sewing machinist at the Ford factory in Dagenham, being the key figure. In remarkably quick fashion she rises from being the group’s wallflower to become the head of the fight for equal pay for women, and drags her colleagues through a series of increasingly difficult challenges that despite their apparent toughness, they never once look like they’re going to lose.

These include: pushing for strike action against the wishes of Dagenham’s bosses; arguing for solidarity from the rest of the unions in the face of sexism and deal-brokering from the politically compromised union hierarchy; working a deal from Barbara Castle in minutes despite massive pressure on her from Ford’s American top brass to force them back to work and various other personal traumas, including those involving Connie, her best friend and former shop steward whose husband is suffering from World War II-related PTS.

Of course, you know before you’ve even sat down what these remarkably tough women have done, so whining about spoilers gets no sympathy from these quarters. And indeed, that’s the whole point; the journey to the inevitable victory isn’t as important as how that story is told to us, and broadly speaking Cole has done a decent job of making a warm-hearted Brit Flick in the tradition of The Full Monty and Calender Girls. He’s achieved this by stripping out the nuance. We have a clear idea of who the good and bad guys are from the beginning: the women are all chirpy, lively, and end-of-the pier saucy, while Ford’s management are slimy and incompetent, and the union bosses are cowardly, sexist and corrupt. After being set up as a honourable union man and committed to the issue of sexual equality ("Me mahm worked all her loife for naffink – it was aaaaard"), Bob Hoskin’s character, union representative Albert, spends the majority of his time on screen poking his head through the cabin door to say "I just want to tell you good luck, we’re all counting on you." That’s not to slate Hoskins, who actually brings a lot of charm and humour to his role, or even the film; it’s doing what it set out to. It’s just not doing it in a particularly subtle manner.

However, and this is key, it’s clear these people are the deserving poor, the people who had to put up with terrible pay and appalling conditions, and who were fighting against a clear and recognisable inequality within their own social class. They are not the union men of today, who are only striking to protect their cushy public sector wages, and who have the temerity to not have it as shitty as us poor bastards in the private sector. Only the most curmudgeonly Mail or Telegraph reader could have anything against these ballsy, brassy, white women: however I doubt whether people will make the connection between what these Union Girls fought for and what British Airways cabin crew are fighting for right now. After all, they never ruined your weekend break to Tuscany.