The political power of the traditional mass media may be fading in front of our eyes, but you can bet that newsprint’s last stand will be in creating entirely fictitious moral panics, a tradition as old as the printing press. This artful thriller fell foul of self-appointed moral arbiters on its original release in 1977 and has gone unseen for decades save for a long lost, cheapie-screamie VHS.

Now impressively repackaged and remastered by the BFI (it comes paired with Bob Bentley’s 1981 BAFTA-winning rural horror short Recluse, also based on a true story and in fact filmed on the very farm where the murder-suicide that inspired it took place), we can again wonder what the fuss was about. For Ian Merrick’s low-budget film is anything but prurient and relies on timing and suspense for its impact. Ironically, it pulls its punches rather than explicitly expose the complicity of the press and police in the unfortunate fate of kidnapped heiress Lesley Whittle, not that they returned the favour.

For those under forty, ‘The Black Panther’ was Donald Neilson, an ex-squaddie, itinerant builder and habitual housebreaker whose crimes grew ever gorier as he took up murdering rural postmasters for puny rewards until he was ready for the big one, a lucrative abduction. The case is well documented. A mix-up over the ransom drop meant that Neilson never received the money. Whittle may well have been left to starve after a spooked Neilson fled and, held by a neck ligature, fallen to her death. Although Neilson was guilty as hell of many crimes, maybe over four hundred burglaries for a start, he always denied her murder. This scene is actually fudged in the film, presumably as part of a determined attempt to avoid legal complications.

Growing up hearing about his trial on the news (he had been accidentally captured outside a Nottinghamshire chippy after an unrelated offence), I knew Neilson was a bad ‘un and the movie confirms my suspicions. As the killer Donald Sumpter is impressive, tightly wound, a slight man somewhere between Steve Coogan and Jimmy Nail, but with all humour removed. He runs through the woods with a rucksack full of bricks, certain that one day they’ll be gold bars. He’s an early scrapbooker, saving all his press cuttings, even the ones that detail his failures. He can catch, peel and cook a wild rabbit. (Actually, the meat looked rather pale – did the filmmakers get one from a pet store?)

Neilson is a man of endless surprises, offended by dirt, clearly fascinated by the contents of army surplus stores, in love with the idea of a control he can’t achieve in his day-to-day existence of petty crime and snapping at his wife and kid. He’s a felonious handyman, making use of every lesson his erratic, unfulfilled life has taught him. He can dance, map-read, kill without flinching. (The irony of an avowed racist sharing his nom de crime, invented by a resourceful hack, with America’s leading black liberationists goes unmentioned.)

Extremely well made by a talented team of Brit hopefuls delighted to have evaded the sexploitation trap, it’s nonetheless easy to see why this was derided by the morality brigade: it’s so downbeat, the ring of vérité is unmistakable. Lesley Whittle really did die in a sewer drain, just like the one they filmed in, and only a few months before the scene was shot. It’s so matter of fact it’s uncomfortable to watch, and Sumpter is so weird, his accent always changing, talking in functional clipped phrases – half military, half retarded. Yet it’s undeniably effective, and barely dated. Even its 1970s drabness is the stuff of present day television histories and overwrought drama, all candlewick bedspreads and rented televisions.

In fact The Black Panther came to fruition by accident. Director Ian Merrick, just back from New York where he saw filmmakers shooting on the run with limited budgets, realised that he could do the same, and budgeted a movie at a hundred grand, chickenfeed even then. Yet his distributors forced him to ditch his original conception: an army-trained assassin leaves the service still programmed and plans to wash all the scum off the streets, putatively titled The Park Keeper (how British). They wanted the story of Donald Neilson. Even in the gloomy ’70s, serial killers, like soul music and hamburgers, were an American thing. Lesley Whittle, scion of rural transport millionaires, was our lost heiress. Theirs was Patty Hearst, a descendent of the man who started a war between Spain and the United States.

For the United Kingdom to have produced one of its own was certainly filmworthy, even if his own QC warned the jury that though they may "have heard much about Mr Neilson and ‘The Black Panther’, you may, when you have heard of this man’s pathetic attempts to ‘make it big’, think rather of The Pink Panther and Mr Peter Sellers." Personally I would have gone with ‘The Black Pudding’ (which would have also curtailed Peter Sutcliffe’s murder spree, for fear of being labelled ‘The Yorkshire Pudding’).

Yet this is anything but a crass cash-in. Screenwriter Michael Armstrong based his terse script directly on witness and court accounts, later comparing the process to "an autopsy" rather than a work of imagination. Only the scenes underground with the abductee reflect Neilson’s version, and they are at least sensitive to the truth of the situation – a dead hostage is worse than no hostage at all. Merrick’s close-up style might have been influenced by financial considerations, but it’s so intimate it’s like following a criminal on his rounds.

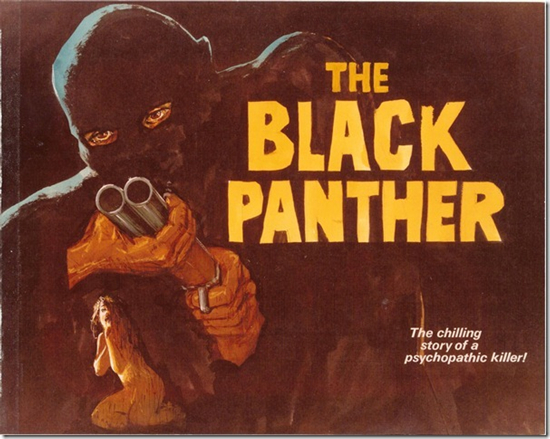

The advertising was less subtle (see 1980s video trailer above), the word ‘PSYCHO!’ featuring prominently. But this is better than a mere curiosity. The mid-’70s recession meant that Merrick could use top talent and locations for a relative pittance; at one point his was the sole feature in production at the Pinewood Studios complex, with corresponding savings. Donald Neilson died in prison last year. The art of making a movie better than it need be has yet to leave us.

A Dual Format Edition of The Black Panther is out now via BFI Flipside.