Growing up on a British Forces base in West Germany at the height of the cold war in the late 70s and early 80s, there was a lot to be anxious about: regular bomb threats; soldiers and military police wandering about with automatic rifles slung; army Land Rovers driving around our suburban street in the dead of night with roof-mounted loudhailers summoning officers to practice what would happen in the event of a nuclear attack. But few things burnt themselves into my consciousness like seeing the then-tattered but still infamous wanted posters of the Baader-Meinhof Group – or Red Army Faction (RAF) – in the local German post office.

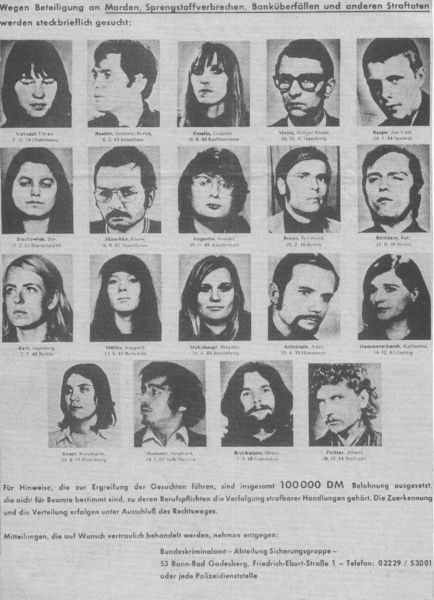

The nearest thing modern society had to the stereotypical Wild West ‘Wanted’ bills – they even included a 100,000 Deutsch Mark reward – the posters featured 19 passport-style black and white photos of each known RAF activist. Every time another member of the gang was caught or killed, their mugshot was uncompromisingly struck through by the authorities, as if they were simply ticking off so many tasks on a list.

As an eight-year-old, at the time I had little understanding of what these people were doing or what they had done – perhaps other than they were desperate bank robbers. By the late 70s, the poster was already a remnant – a recent stark reminder of Germany’s politically-charged, violent domestic upheaval of the past decade when the final legacy of the Second World War came home to roost. By then, most of the group had been caught and the core members were already dead. But I can still recall the nightmarish terror that the poster and its grainy images instilled. On the weekly Saturday morning shopping trip to the NAAFI, I would look the other way when we walked past the post office – just in case I accidentally glimpsed the poster through the window.

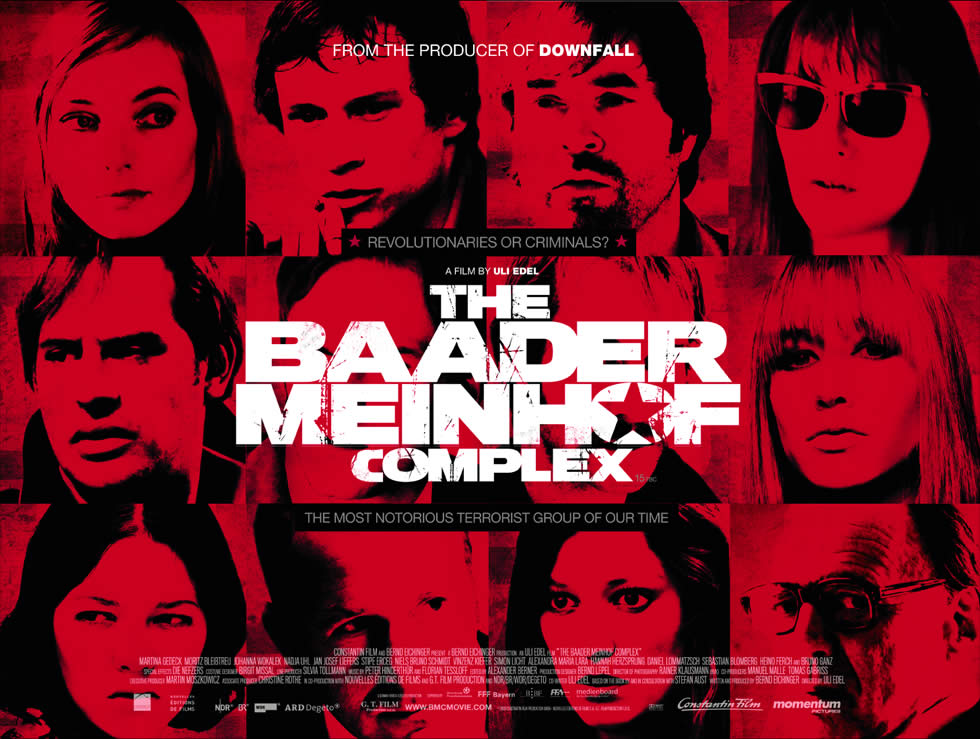

The fractional poster image features heavily in both the recent German-made feature-length movie The Baader Meinhof Complex (remade featuring photos of the movie’s actors), the movie’s associated advertising and the cover of the book on which the film is based: Stefan Aust’s impressively researched and thoroughly-detailed book of the same name, originally published in 1985 and now updated with new evidence and a new preface by the author.

Aust – played by Volker Bruch in the movie – was close to the Baader-Meinhof Group without taking part in its activities. A student journalist in the late 60s, he worked on radical student paper Konkret alongside Ulrike Meinhof, someone whom he admired. Aust later pursued a career in the German mainstream media, culminating as Editor-In-Chief of revered German newspaper Der Spiegel and most recently, founder of Spiegel TV. The Group attempted to kill Aust when he rescued Meinhof’s daughters from a future in a Palestinian orphan camp to be trained as guerrillas. But he was also targeted this year following the film’s release. Aust’s home was attacked with paint bombs and bricks – some of which landed near his children’s beds. “We thought the whole thing was history,” Aust told The Telegraph. “So I was surprised – shocked.” Police rule out the involvement of the RAF, who finally gave up their association with armed struggle in a statement delivered to Reuters as recently as 1998.

Aust’s involvement as a consultant for the movie (directed by Last Exit To Brooklyn’s Uli Edel, it’s already been nominated as Best Foreign Language Film for the 2009 Oscars) is evidential: except for a few minor details, it is very historically accurate. But it’s such minor details that had the German population up in arms upon the film’s release. It came under heavy criticism for glamourising the RAF and their apparent radical chic. With full frontal nudity, sexy-looking actors playing anarcho-terrorists and a wardrobe featuring mini-skirts and dresses of the 60s’ permissive society, it was too much for a lot of the German populace. Ulrike Meinhof’s daughter Bettina Röhl, now a journalist herself, described it as “hero worship” in German newspaper Die Welt.

The atrocities performed by the RAF gripped the national German psyche and are for many Germans, not least the relatives of those killed in bomb attacks, assassinations or kidnappings, still too recent to be the subject of a movie. But unless Aust’s book had been adapted as a documentary, such glamourisation is inevitable in feature length movie making. That said, some of the characters’ portrayals seem way off the mark. Rudi Dutschke doesn’t appear to age between the events of 1968 and 1974, and second generation RAF member Peter Jürgen Boock, played by the smouldering Vizenze Kiefer, looks more like Val Kilmer’s pouting portrayal of Jim Morrison rather then the reality of the mullet-haired and mustached drug addict.

But conversely, besides Ulrike Meinhof (a wholly convincing standout lead role played by Martina Gedeck), it’s hard to sympathise with any of the Group’s members – not least petty thief and opportunist Andreas Baader (Moritz Bleibtreu who also played Andreas in Spielberg’s Munich). A manipulative and self-important narcissist, Andreas Baader described all women as cunts. He refused to swap his velvet trousers for battle fatigues during the RAF’s PLO desert training and according to Aust’s book, ate food smuggled into prison while encouraging his fellow group members to hunger strike: a course of action that resulted in a tragic, slow and painful death for one of the group’s most militant members, Holger Meins. Baader was the archetypal rock’n’roll radical: he liked leather jackets, sunglasses, and fast cars. But he had all the personality of a sociopath. French existential philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre visited Baader in Stuttgart-Stammheim prison and later allegedly described him as “an asshole”.

The second main grievance of the media industry’s movie reviews is the film’s lack of background information and reasons for the group’s radicalisation and activities. This seems something of a surprising claim, as the movie makes this blatantly obvious: it opens with a demonstration brutally suppressed by the German police and makes numerous references to US imperialism – the Vietnam War and the west’s militarisation of the Middle East – precisely why the RAF targeted US garrisons in West Germany. Those watching the movie without background knowledge won’t need to read between the lines.

In the same way one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter, one man’s precautionary policing is another man’s fascist police state. In an age of political upheaval across the world in the late 60s, Germany was still shaking off the long shadows of the 1930 and 1940s: this was a time when those in power and influence were former members of the Third Reich. Sickened by the older generation’s failure and apparent complicity of Germany’s wartime concentration camps and holocaust, the Baader-Meinhof generation saw the country sliding towards a similar fascist state.

As Aust suggests, the German government of the 70s was partially to blame for the RAF’s longevity. Ill-equipped to deal with passionate and highly self-disciplined fundamentalists ready and willing to die for their personal politics, West Germany’s Federal Democratic Republic (FDR) made some stunning mistakes, not least the nature of the RAF’s imprisonment, Stammheim prison’s breathtaking lack of security and a public trial that can only be described as farcical. To worsen matters, the FDR’s pursuit of the Baader-Meinhof Group wasn’t supported by all strata of German society. A poll carried out before the group’s incarceration concluded that one in four Germans under the age of 30 sympathised with the RAF.

In terms of their politics and agenda, the RAF were ahead of their time. Only this decade has protest against US imperialism reached the mainstream consciousness in the form of anti-Iraq demonstrations, and protest against globalisation at G8 summits. It’s taken once-unthinkable terrorist attacks on the US mainland, but a full 30 years later, the USA’s current President-Elect is pledging investment in alternative forms of energy to lessen the USA’s reliance on oil-rich Middle-East states. Environmentalism itself also came from the political underground of the same era.

An impressive pioneering of social politics, maybe. But it doesn’t justify the RAF’s murderous actions. The late 60s was a period of political awakening for the entire world and while Baader and Ensslin were setting fire to department stores, across the border, the French anarchists were instigating a revolt of their own: a cultural revolution. Guy Debord’s Society of The Spectacle and the Situationist Internationale influenced and inspired both art and socio-political movements of today, such as punk rock, the rebirth of psychogeography, Reclaim The Streets, Adbusters, countless underground publications and the works of respected writers from Peter Lamborn Wilson and Bob Black to Stuart Christie and Stewart Home.

The Baader-Meinhof Group inspired nothing similarly artistic. They simply inspired subsequent terrorist groups. With spectacular campaigns such as Brigitte Mohnhaupt’s (who was eventually released from prison last year) organisation of the hijacking of a Lufthansa jet to blackmail the release of the RAF’s core members, inevitable comparisons have been made between the RAF and Al Qaeda. Movie reviewers outright deny any similarities but Aust makes the link in his book’s new preface. He compares the impact of the RAF on Germany during the 70s as equivalent to that of 9/11 on the USA. “Terrorists regard themselves as martyrs,” he writes. “The Attas and Baaders of this world have much in common – each in his own time, but always embedded in a revolutionary mainstream whether of a socialist or, as present, an Islamist nature. Both Mohammed Atta and Andreas Baader came very close to their aim of gaining immortality through their deaths.” At the same time, it’s easy to draw parallels between the RAF’s condition of imprisonment and the reported treatment of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay.

The RAF’s ideology and actions are still lauded by some parts of the current anarchist underground, not least those who still believe the core members of the RAF were murdered in their cells by extra-judicial killings rather than having committed suicide. Icons or anti-heroes in their own right, photographs of Baader, Ensslin and Meinhof’s suicides feature in New York’s Museum Of Modern Art’s permanent collection. The myth of the Baader-Meinhof Group refuses to die and 2009 promises even more new literature on the subject.

Richard Huffman – who also runs www.baader-meinhof.com – aims to publish a thorough examination of the RAF in The Gun Speaks: The Baader-Meinhof Gang At The Dawn Of Terror in late 2009. Underground publishers PM Press and Kersplebedeb will jointly publish The Red Army Faction, A Documentary History: Vol 1, Projectiles for the People by J. Smith and André Moncourt in February, promising to be “by far the most in-depth political history of the Red Army Faction ever made available in English”. André Moncourt is also the author of We Were So Terribly Consistent: A Conversation About the Red Army Faction, slated for publication by Kersplebedeb in early January. It features an interview with second generation RAF member Stefan Wisniewski who was integral in the group’s kidnapping of German industrialist Hanns Martin Schleyer.

The Baader-Meinhof website is testament to the RAF’s impact and how they are viewed in the new millennium. It features a store linked to Amazon listing all the books so far published in connection with the RAF, but it also has something rather more macabre on offer for $20 a pop: a souvenir replica of the original Baader-Meinhof Group wanted poster.

The Baader Meinhof Complex movie is on general release now through Momentum Pictures. The Baader-Meinhof Complex by Stefan Aust is available now in paperback, published by Bodley Head.