There have been many many films made over the years featuring unsuspecting young people getting butchered with otherwise innocuous household and DIY appliances – and some bona-fide classics are among them – but the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre might very well be the greatest, most disturbing and most luridly unhinged example of the teenager-meets-masked-lunatic cinematic form.

Tobe Hooper’s 1974 horror masterpiece both defined the slasher genre, and transcended it, and four decades on from its début it has lost none of its unsettling power. To celebrate its 40th anniversary the film has received a 4K restoration, and will be re-released on blu-ray (which is rather nonsensically coming out in the middle of November in the UK, as opposed to its actual anniversary in October, but hey that’s your problem you kooky blu-ray releasing business people you.)

The lasting legacy, and undeniable quality of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre defies easy explanation. Tobe Hooper himself would never make another film as accomplished, though there is much to be admired in the camp horror-comedy weirdness of his Texas Chain Saw Massacre 2, and the great Poltergeist (although the jury is still out on exactly how much credit he deserves for that one.)

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was a no budget production by people just out of film school, yet somehow the finished product became something so much more than the usual exploitation fare of the period. Wes Craven’s Last House On The Left came out two years prior, and is far more extreme in its content, but revisited now it’s a piece of outright incompetence that skates by on raw shock value. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre on the other hand is a raw but artful nightmare of surreal intensity, filled with startling moments of scorched low rent beauty.

The plot is as simple as they come; a group of young people in a van travel to the deep ends of Texas to visit the now abandoned ancestral home of two of their members. One by one they inadvertently stumble into the clutches of a family of deranged cannibals, with the human skin wearing, chainsaw wielding Leatherface being the most memorable and dangerous family member. Eventually everyone is butchered until only Marilyn Burns’ Sally remains.

On paper it all sounds very ordinary, but in execution it’s far more vivid and dangerous than all the countless shoddy slashers that would follow in its wake. The grimy pseduo-documentary visual aesthetic contributes enormously to the film’s power, and the way it was disingenuously marketed as being based on a true story only contributes to the sense that the viewer is a fly on the wall witnessing actual murder. In that sense The Texas Chainsaw Massacre helped invent the found-footage genre just as much as it did the slasher; so like any true horror innovator the cinematic crimes it inspired are surely far greater in number than those old Leatherface got up to.

The film’s unique sense of pacing further accentuates the terror and realness of it all. There’s a mounting sense of dread before the killing starts; dead armadillos on the road, the radio blaring out endless news stories of death and despair, the encounter with the deranged hitch-hiker, all lead to an escalating unease. But the actual murders come swift and unexpected. There’s little Hitchockian build up to tell you what to feel. Instead death, horror and inexplicable insanity are a concrete presence, lurking behind innocuous screen doors, waiting for you to make the wrong step. Once you do death is instant.

It feels all too real, and surprisingly, despite the film’s infamous reputation for brutality, there is very little blood and gore depicted. Instead it’s mostly left to suggestion, as Hooper was rather outrageously aiming for a PG certificate for the film. The lack of comical splatter, and such visceral details as a body convulsing after receiving a blow to the head, makes the violence you do see that much more brutal and disturbing.

Of course once you stumble upon murderous insanity, it’s hardly going to let up. The final 30 minutes of the film are sadistically unrelenting, as poor screaming Sally is pursued and harassed without a moment respite. Such unflagging energy shouldn’t work, but instead the madness of it just ramps up and up to surreal and disturbing new heights, cumulating in the dizzying dinner party scene. There’s a palpable frenzy and insanity in the air, and by all accounts it was genuine. The scene was shot over 27 consecutive hours of filming, made more hellish as the room was poorly ventilated, and a heatwave was in progress. Many of the props were made from genuine rotting animal parts, and Gunnar Hansen, who played Leatherface, stank to high heaven due to the fact that been wearing the same costume for a month of filming (the production couldn’t risk washing and losing it, or afford a second one). As the stories have it Hansen was so deranged that he literally cut open Marilyn Burn’s finger as the prop to cause blood to squirt was malfunctioning. It’s hardly an ethical or reasonable way to make a film, but that lightning in a bottle atmosphere of true mania is very apparent on the screen.

Much has been written about the subtext of the Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and there’s a richness and intelligence in its sparseness that offers a multitude of interpretations. It taps into the summer of love hangover and Vietnam malaise of the early 1970’s, and it can even be read as being about animal rights: the parallel between cows for the slaughter, and destined to be eaten young folks is made horribly explicit.

Perhaps most interesting is the warped family dynamic between the cannibals. Leatherface is the most lethal, but he’s also the maternal figure – made evident by his cross dressing and literal donning of a woman’s face, while the schizophrenic, more violence averse cook plays the father figure, with the deranged hitch-hiker as the trouble-strewing teenager. You can read it all as being a representation of the break down in the nuclear family, or a comment on the deranging effect of unencumbered masculinity, but crucially it’s just freaky as fuck. The latent black comedy of their family bickering heightens the surreal horror of being tied down to a chair while cannibals feast on sausages made from your friends.

The family dynamic also makes Leatherface a far more believable sort of mask wearing murderous lunatic. He’s a mentally ill cannibal who gets bullied and bossed around by his family, just as he gets more and more upset by all these damn teenagers he has to kill. His vulnerability, as well as his human skin wearing, chainsaw wielding nature, make him far more freakish and credible than the masked emotionless super-humans of the second rate slashers to follow.

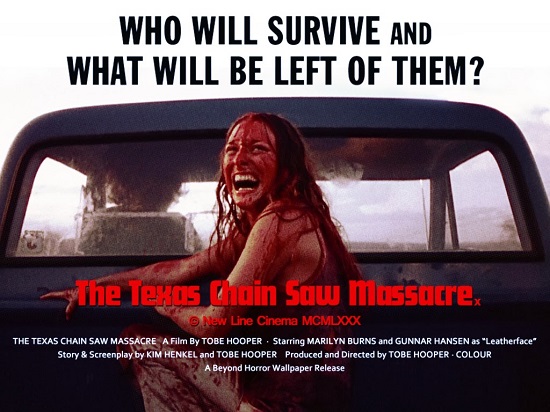

And then there’s that ending, not just the greatest ending to a horror film, but one of the greatest endings in all of cinema; Marilyn Burns laughing hysterically having escaped onto the back of a pick-up truck, and Leatherface inscrutably dancing and writhing in rage, chainsaw hoisted aloft as the sun rises, followed by a jarring cut to black. It’s a visually beautiful, exhilarating, and disturbing image of authentic madness, and it never fails to hit like a bolt gun to the head.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is an inexplicable masterpiece, much admired and copied, but never to be repeated or bettered. Somehow a curious alchemy of the right people, the right time, and a flagrant willingness to abuse cast and crew, all combined to form an impossibly gritty, deranged, piece of horror genius. Somewhere out there, in the nondescript corners of the world, there’s a chainsaw with all our names on it.